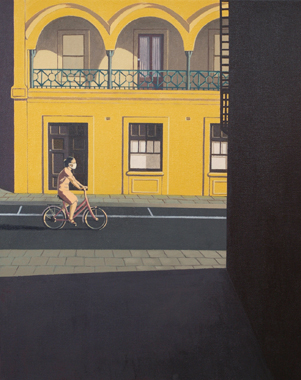

60cm x 40cm

oil on canvas

Courtesy of Hop Dac

I have travelled a long way with the water

carried downstream and ushered out by the river mouth

floated on a paper boat much like ones I would learn to fold

in childhood, haunted by the estuary and the sea, retreating

like folk stories my mother would tell in the kitchens of the places we settled in

old songs sung from mother to son; recitals that would lose their meaning

as dreams that shrunk under my touch and sunk into the depths of memory’s bunker.

I have travelled a long way with the water

And exposed under the open sun I vaporised unlike anyone

I played uneasily; a fish emigrated to an aviary

where a procession of unfriendly faces pestered and pecked

Whenever it was deemed necessary. Arbitrarily

So I waited, through years and lives stagnated

In a nation, like an institution, mollycoddled by convention

With ambitions that listed to the side of caution ad nauseam

More pastoral in temperament than urban.

I have travelled a long way with the water

and drifted between tides of dejection and euphoria

too changed to ever return and too strange to ever feel sure

I was a juggler struggling with these orbs airborne

Like a hypocrisy siding with self-preservation

In sermons made on the subject of compassion

In parliamentary apologies made for a past of wrongdoing

Like drowned bodies seen and not worth retrieving.

The wariness between us, the space occupied by you

fractions of consent edged us closer to a truce

This is being normal I would call ‘making do’

Being abnormal is preferable to me, in truth.

I have travelled a long way with the water

A breath that broke the skin

a droplet transported by gaseous waves and solar winds

I moved through ages along with the glaciers

in volumes from monsoons, cyclones and typhoons

by rains and showers, into drains from boughs

from wars and famines and other desperate hours

A stranger in a familiar land regardless of where I am.

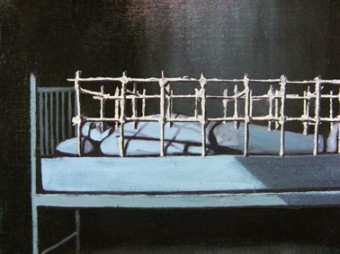

Detail of diptych

Oil on canvas board

courtesy of Hop Dac

—————————————

A painter who writes – interview with Hop Dac

Hop Dac is a painter and writer who calls Yarraville home. He was born in Vietnam, but his formative years were in Geraldton, Western Australia. “Growing up Asian or Vietnamese in the 80s was pretty shit, at least in a country town. You’re constantly being reminded about your differences, and it took me a long time to accept that and to know that I wasn’t necessarily normal in an Australian context and to be perfectly happy with that”. However, it wasn’t until later, that he could appreciate his bicultural identity, “I think it wasn’t until I was in my mid-20s when I started to really appreciate that and think about it, and started to investigate what it meant for me in the landscape that I grew up in, in Australia and how that affects my psyche”.

Hop’s family fled Vietnam by boat when he was two and spent five days at sea. Their smaller vessel was met by a larger one and all the women and children were rescued, but left behind were the men, including Hop’s dad. Hop was with his mother and his younger baby brother, Tam, a few months old. The larger boat landed them in Indonesia.

“I have a memory of going down to the wharf with my mum at that time looking for my father, who miraculously also showed up a few days later. We stayed in Indo for a month and were then flown to Singapore, where we stayed for three days, I think, and then flown to Perth, where we were processed at Graylands, which was a psychiatric hospital temporarily set up for processing Viets. We lived in Perth for two or three years until my family moved to Geraldton, a coastal town 450km north.”

Growing up with the experience of not being “necessarily normal in an Australian context” also impacted his writing life. “It’s a fraught relationship. It’s taken me a long time to come to writing about being Asian and that aspect of myself, and how that is expressed and what that is like”, says Hop. However, writing from the framework of his Vietnamese/Asian identity is not his only lens.

“I enjoy writing Australiana stories, I enjoy writing about people in country towns that aren’t necessarily Asian. Or sometimes there are Asian characters. It’s just more about writing about a little bit of life rather than being too focussed on what it’s like to have that Asian experience, and while I do go there to that place sometimes, it’s not something that I feel my work necessarily needs to explore too much. I don’t find that part of my identity is all that I am, and there’s a lot to write about and there’s a lot to reflect on, and that’s part of it, but that’s not all of it.”

When I ask how he defines his art practice, Hop jokes that his art practice is “ill-disciplined”. Says Hop, “I’m at the point where I need to wake up early each day and write on a daily basis or paint on a daily basis. I need to pick up my practice a bit more. You can bludge your way through on your god-given talents and you can get so far, but it doesn’t really help you in terms of establishing a career or getting to a point where you can do that professionally”.

Curiosity about how other people live is a driving force in Hop’s art practice, brought upon by a sense of alienation from his childhood in Geraldton in the ‘80s. In Hop’s keen eye, this scrutiny developed “to a level of minutiae where it’s about how people live emotionally or how they interact daily to get by, to survive, to get along, or to build their lives around each other”. “I guess I’m curious about that because it helps to inform how I live and the decisions that I make but also because it becomes a fodder for writing material as well. It was horrible growing up like that, with that almost voyeuristic watchfulness, but the benefit in hindsight is that I have developed an acuity or facility to notice how people relate to each other, whether that’s on a male-female or otherwise relationship or in a racial context or sexual or whatever. Those things they all have similarities you can become aware of, but, perhaps ironically, it’s the differences that help you pin down a human experience,” says Hop.

Some of the authors that write about place that Hop admires include James Joyce writing about Dublin and Christos Tsiolkas writing about Northcote in The Slap. In Hop’s own work, he likes setting his stories in real places, whereby writing about place allows him to pin and contextualise a story. Says Hop, “I enjoy that sort of story writing because it makes it more vivid and real, but when I write about place, a lot of it is tied in with identity. How identity is created or informed or influenced by the places that you grow up in. I know with my art practice and having gone through art school you develop an intellectual appreciation for place as a concept, which can inform your practice. On a practical level, when I’ve got an art studio, I’m quite anal with the way it’s set up and having things in the right place so that I feel like I can work”.

In his past writing work, including a piece for Peril called “Cuisine”, Hop acknowledges that there is a particular sentimental or reflective quality to them, writing about Geraldton has come up frequently.

“One of my earliest memories, and I’ve written about this, was living in Perth when I was four, after arriving in Australia as a boatperson, of flying over paddy fields, and it was a very vivid memory at the time which I still carry with me. When I went back to Vietnam when I was 21, I went to Can Tho, where my dad’s side are from – they are all paddy or rice farmers – and standing there seeing my grandad’s land where he was a rice farmer, I realised that’s where I was flying over, and that really did something to me in terms of appreciating the landscape where I came from, and then putting that into context of the landscape where I grew up in Geraldton and how vastly different that was”.

According to Hop, the thread of how his “identity has been sewn to places in the past”, has led him on a journey of discovering meaning behind names, again tied to place. “I should mention that my grandad used to be a poet. He was a rice farmer, but he also wrote poems and short stories under the pseudonym Phi Huynh, which I think means firefly. When I went back to Vietnam, I was pissing into the Mekong one night and a firefly threaded its way past me. I hadn’t appreciated until then what a little bit of magic that was,” says Hop.

Hop’s grandfather – Bich Van Nguyen – wrote satirical political poems and short stories that were published in a newspaper called Saigon Moi or New Saigon, which was distributed throughout the south of Vietnam. According to Hop, his grandfather was published up until the early 60s, when the newspaper was shut down. However, his artistic expression wasn’t appreciated by the authorities and he was incarcerated about half a dozen times because of his poetry.

“He would be incarcerated for six months to three years at a time. The first time it happened was in 1950. The Vietcong put him into a labour camp to do stupid things. One of the stupid things that my dad told me about – so the prisoners would have to go and clear land or whatever thankless task the Vietcong wanted you to do, and grandad’s job was to feed everyone. They had given him a big sack of rice, and said cook this up for everyone, but hadn’t given him any pots and pans. He didn’t know how he was going to cook all this rice for however many people. So what he did was he dangled the entire sack of rice into the river, letting it soak up water overnight so the grains softened. When he pulled it out, he covered the entire sack in river clay, built a fire pit, dropped the sack in and covered it up. I thought it was a fucking ingenious way of dealing with the situation”.

Discovering that his grandfather was a poet moved him deeply, the thread of his identity deepening even further with a discovery that his grandfather too was an artist. Unfortunately this artistic appreciation wasn’t always shared by his extended family. In a return journey to Vietnam at 21, Hop visited a cousin who had kept his grandfather’s poems.

“They were in a plastic bag and they were being eaten by bugs, disintegrating badly. I really want to go back to get them, and have them translated if they still exist. I don’t know if they’ve been eaten up or been thrown out, but that’s something that I really want to do”.

According to Hop, he identifies an aspect of himself as an Asian-Australian writer or artist, however is wary about being pigeonholed. “I know I have the luxury of being able to go into that world and doffing that hat. Like my grandfather, I write under a pseudonym and in a poetic sense, having that pseudonym as a creative entity that you can have a relationship with on a creative level, I find that more interesting,” says Hop.

For the Peril Map, Hop is contributing “A stranger in a familiar land”, a poem written “largely in response to the government’s decision not to retrieve the bodies of asylum seekers that had drowned recently”. Here Hop is referring to the decision made by custom officials not to retrieve at least 55 asylum seeker bodies presumed to have drowned off Christmas Island. “I thought that was abhorrent and wanted to frame it within my own experience,” says Hop.

In terms of pinning his biography to a place, Hop is choosing to pin to Western Australia.

“Geraldton as a place probably holds the most significance for me but I love Melbourne because it’s ` everything I didn’t have growing up.”

~ interviewed by Lian Low