He rubs his worn cock against the over-heated screen of his mobile phone. He swipes right impatiently through a feed he has curated to see ‘women between the ages of 20-44 only’. The tip of his cock rests a little longer on the face of a woman he would harden up for. The face that reads ‘love you long time’ in the slant of her eyes and in the smoothness of her skin – that is the face he is looking for.

He is watching out for me.

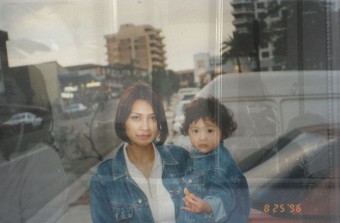

White men have been watching me and my mother since I was a teenager. Their eyes roll over the curve of our eyes and wrap themselves around the softness of our thighs. From the asian mother who makes countless sacrifices for her family, to the young international asian student engaging in sex work to financially support themselves and their family. Patriarchal society reduces us to these tropes and shames us for existing in them, and in return, we live, struggle, and fight our way through racial and sexual violence. We experience these forms of violence such as sexual assault, rape, intimidation, and shaming as soon as we walk into a room, online, in dating, at the train station, and even at home.

In my teen years, I began to notice how desirable my mother was. I would always hear from vietnamese and non-vietnamese people about how beautiful she was and in the same sentence how she did not look vietnamese, instead she looked ‘lai’ (the word for mixed-race in vietnamese). Historically, the word lai has dirty connotations. It is associated with betraying the purity of vietnamese culture and partaking in dirty collaboration between colonizer and colonized. My mother was the result of this collaboration. Born into this world as French-Vietnamese marked her as undesirable to vietnamese culture and sadly, even to her own mother. On the other hand, her mixed race features rendered her as desirable in western culture. When I was in primary school, my mother was always a prize to the eyes of my white friends and teachers. She always picked me up from school, took me out shopping, and she was the parent who spoke english better than my father. She became the trophy in my eyes whilst my father was casted as ‘too vietnamese’ and therefore embarrassing to be around with in public.

I did not want to be asian or vietnamese and this was equally bound up with not wanting to be a woman. My mother was always praised for her lai beauty, but this also marked her as a target for a man’s oppressive behaviour. Perhaps this is why being asian, vietnamese and woman were labels I never wanted. They were labels that reminded me of a lurking violence that I could only blame on the patriarchal values embedded in not only western culture, but vietnamese culture too.

As a queer, genderfluid, lai person, I have been told in various stages of my life that I do not pass for a vietnamese person nor a vietnamese woman. These remarks have come from both non-vietnamese and vietnamese people. In June 2015, I was with my grandmother and aunty in Việt Nam. One morning I wore my usual shorts and shirt outfit and my aunty asked, and then insisted, that I wear one of her dresses. I politely declined and said I was comfortable in my clothes. Then my grandmother, in her humble way, giggled at me and cheekily said in vietnamese, “no one thinks you’re vietnamese because you look like a girl on top and a boy on the bottom”. I realized that my height, skin colour, physical features and the way I dressed did not allow me to pass for vietnamese, nor a vietnamese woman.

In the eyes of my aunt’s and grandmother’s generation I was supposed to reflect my status as a Việt Kiều. Việt Kiều are vietnamese people who were born or permanently live outside of Việt Nam. They are viewed as wealthier and more privileged than those living in the homelands. Since I did not authentically reflect this image of a Việt Kiều, I was always watched whenever I walked down the streets in my grandmother’s homelands. I was watched because I was an outsider walking arm-in-arm with a person who was a clear insider to vietnamese culture and a place I did not know if I could call home.

Five months later, I returned to Việt Nam, but this time, on my own without family. I went on my own for several reasons, including to learn about being a queer genderfluid vietnamese person and what that meant in the context of the queer world in Hà Nội. I made some truly wonderful friends, but inside I was emotionally clogged with loneliness and anxiety. I felt undesired by this place, which, in my mind, was supposed to be familiar and comforting for me. In hindsight, I was putting too much pressure on myself to have a certain experience of the homelands. During my time in Hà Nội, I joined Tinder which on the most part offered an all too familiar experiences for me. I was exoticised for not only being ‘asian’ but also for being a Việt Kiề, queer and portraying myself as sexually dominant. I heard the all too familiar remark, “you’re different to other vietnamese women”, which became my stamp of desirability for white men. On the contrary, my lai features marked me as desirable to vietnamese men. Having this overt attention from men felt draining, especially given that deep down, I was chasing to be loved by a place that struggled to love me back.

If I can only be visible when I am authentic then visibility has failed me. Visibility has been used against me.

I then wonder, at what point will I stop being the asian that patriarchy watches out for? And at what point will I become the asian who is holding the lens onto themself? Perhaps holding my own gaze begins with moving through the world invisibly and crafting the way I use it. Vietnamese writer, artist and academic, Trinh.T. Minh-Ha, speaks of positioning ourselves as the Inappropriate Other; to embody both deceptive insider and deceptive outsider. When we embody the Inappropriate Other, the question of authenticity becomes irrelevant and our invisibility becomes our power. Authenticity has historically and continues to be used against people of colour and Indigenous people around the world. In my instance, it is used against me for being asian, vietnamese, lai, and even queer. The idea of ‘passing’ is bound up with a construction of authenticity that is too high of a standard to ever measure up to. In the cases where I did not ‘pass’ as vietnamese, I was deemed as inauthentic. I was undesirable in my grandmother’s culture yet desirable by western culture. Patriarchy has nothing to do but watch out for me. It will stalk me until I give up. It wants me to give up on myself and my asian femme community, but I have a message for patriarchy:

Patriarchy, I do not need you to watch out for me, because I am watching out for myself, my mother, my asian sisters and asian femmes.

*photograph collage by Xen Nhà feat. mẹ với con.

1 thought on “holding the lens onto myself”