2013 marks the 21st anniversary of the controversial Australian film Romper Stomper, released in late 1992, about neo-Nazi skinheads living in Melbourne. I was in grade ten at the time, living in a country town called Geraldton on the Western Australian coast. The film’s release and its effect on the student population of the Catholic boys school that I attended became a flashpoint in my life, a time when all the casual racism that I had experienced up until then focused into a few months of almost daily intimidation.

2013 marks the 21st anniversary of the controversial Australian film Romper Stomper, released in late 1992, about neo-Nazi skinheads living in Melbourne. I was in grade ten at the time, living in a country town called Geraldton on the Western Australian coast. The film’s release and its effect on the student population of the Catholic boys school that I attended became a flashpoint in my life, a time when all the casual racism that I had experienced up until then focused into a few months of almost daily intimidation.

Throughout the 1980s the Vietnamese population of Geraldton had swollen to several hundred people, considerable given the town itself only numbered some 20, 000 inhabitants then. Vietnamese ‘boat people’, as we were known, rather than the less disparaging ‘asylum seekers’ as people seeking refuge by boat have been called lately (with Immigration Minister’s Scott Morrison’s new definition ‘illegal maritime arrivals’ currently in its infancy in the national lexicon), had moved to the town to work on market gardens. My own parents had done so in 1983 on advice passed onto my father after we had settled briefly in Perth. Dad had struggled to find work and fruit picking didn’t require any specialised skills. Many of the Vietnamese workers started their own market gardens, growing tomatoes predominantly, which were then trucked to markets in Perth, sold locally to supermarkets and by roadside stalls.

The influx of the Vietnamese in the late ’70s and early ’80s upset the conservative, parochial community in Geraldton, but they weren’t alone. In Perth and throughout Western Australia, a group called the Australian Nationalist Movement lead by white supremacist Jack Van Tongeren began to disseminate racist posters and firebomb Asian restaurants. Shop windows bore posters warning Asians their custom wasn’t welcome. In Geraldton, racist epithets were simply hurled from passing cars or muttered not imperceptibly on the street and in schoolyards. It was an uneasy time of adjustment for immigrants and locals alike as in many ways all of our lives were changing.

In my experience, the racist name most commonly directed at me in primary school and early high school was ‘nip’, the derogatory term used by the allies for the Japanese from World War Two. It wasn’t until Romper Stomper came out that I started to be called a ‘gook’. That ‘nip’ was still being used some 45 years after WW2 is worth noting for its resonance. The Japanese had bombed Darwin on 19 February 1942, the ‘first and the largest single attack mounted by a foreign power against Australia’ according to Wikipedia. More bombs were dropped on Darwin than were on Pearl Harbor and fears of an invasion spread with the news. In rural communities, these fears seemed to have sat fallow and unresolved long after the war.

The high school that I went to was a Christian Brothers school called St Patrick’s College. There were only a handful of Asian students; I was one of two in my year. St Pat’s also had boarders, most of them had been sent from their family farms or stations in far-flung places like Meekatharra or Mount Magnet to complete their educations. There were also several boarders from Thailand who were a couple of years older than me.

My own experiences with racist confrontations in high school were infrequent until then. Kids in the older years would sometimes call out at me as I walked through the yard. Once, on a particularly bad day in grade nine, I had a number of my classmates call me various things and instead of being able to ignore than as I usually tried to do, I had simply sat down on a bench and cried.

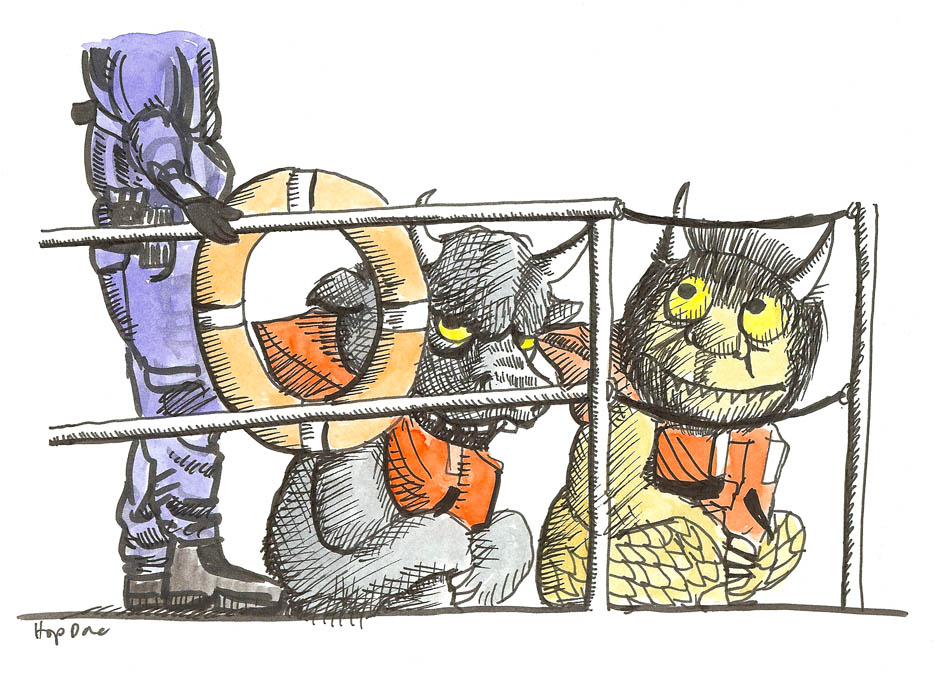

At the end of 1992, Doctor Martin boots were selling at a premium in Geraldton. You could buy them for a hundred and twenty dollars from the army surplus shops or Willocks, a family owned clothing store. Kids started shaving their heads, emulating the skinheads they’d seen in the movie, and in their newly bought Docs they grew vulgar in their packs. Whereas before I would hear things muttered under breaths or witness racist taunts being directed at other kids, I started to have them directed at me explicitly.

Most boys grow up decent. You go through primary school as a foreigner and they don’t really treat you any more differently than anyone else, up until about grade seven, when they begin to hit puberty. Then they can become aggressive, and the aggression becomes a part of the way they relate to each other, especially in the unbalanced world of a boys private school. They will punch each other for fun, burn each other with cigarette lighters, destroy each other’s belongings, and that’s just what happens between friends. Being different in any way is a liability at school, but being physically different paints a target on your back and you can become an unwitting focus for that aggression. When Romper Stomper came out, it turned everything up to eleven. I remember one lunchtime that year, seeing teachers trying to calm down a Thai boarder who was running around the school grounds brandishing a star picket (a steel fence post), blood dripping down his face, looking for the white student who had attacked him unprovoked.

My own most vivid experience was from one of those hot afternoons in year ten. I was walking down a corridor to history class, straggling behind the rest of my class, as I had to get something from my locker, and found myself walking alone past a group of about six year eleven boys waiting in the corridor. I was oblivious to them at first but then they fell silent and turned their heads towards me. They had all assumed the look from the film, shaved heads and shod in Docs, in our private school uniform of grey shorts and light blue, short-sleeve shirt. I suddenly felt threatened and a stutter broke my step as I walked past them. I had almost made it when one of them blocked my way. I looked at him, frozen. He stood there with a smirk on his face and had about thirty kilos on me. It seemed like a long stretch of time that we were looking at each other, not sure which way the situation would go. He was waiting for me to react but I didn’t, instead I was waiting for him to do something. I heard the other boys move around behind me and in that moment I felt as vulnerable as I have ever felt. Yet nothing happened, even as the space around me closed in. There were classes being conducted to one side of the corridor and perhaps that was enough for them to exercise caution. Finally I broke the spell and stepped around the big oaf to hustle my way class. As I turned to exit the corridor I heard them start their chanting, ‘gook, gook, gook’. I never got into fights during high school; all my trauma was psychological.

In his interview with Richard Gray for film website the Reel Bits in 2012 to mark the 20th anniversary of the film, Romper Stomper director Geoffrey Wright dismissed the initial criticism he had received when the film was first released, from figures like David Stratton, that there wasn’t enough editorialising from his part to condemn the characters he was presenting. Wright said, ‘to us it was very clear that, if you’re watching the film, and you see what happens to these people and how the plot plays out, it’s very obvious that two and two equals four’, meaning the audience should be able to take into account how badly things turn out for the neo-Nazis as a way to not be seduced by them. However, when the audience is made up of impressionable boys easily inspired by violence, easily enamoured by Nazi iconography, intolerant and lacking the maturity or deference to question their mob-mentality impulses, let alone have the comprehension skills to appreciate the ultimately tragic narrative of the ideological neo-Nazi in the film; Wright’s assertion that a reasonably intelligent audience wouldn’t be seduced by the neo-Nazis because it doesn’t turn out well for them, just doesn’t hold water. For the people for whom the film would be most dangerous, impressionable young white boys, the assumptions that Wright had of them as a discerning audience was for the most part unrealistic. It’s a difficult thing, reasoning with the pack.

The incident in the corridor was the nadir of that time for me. It’s an incredibly raw feeling, being the centre of attention like that. The tension of violence so thick it almost crackles, with that barbed hook of fear that catches in your breath and hobbles you. To this day I still experience feelings of apprehension walking past a group of people and often I’ll get that stutter in my step. It began for me a long period of introspection and alienation. By the time the next school year had started, kids were starting to grow their hair out again but a part of me remained in that corridor and it wasn’t until I left Geraldton to go to art school in Perth that I began to unravel any of it. Of course by then, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party was only just beginning to gain traction and a new, national expression of parochialism and bigotry began to synthesize. In my mind at the time it seemed to be a natural progression.

As an aside, I’ve heard it said by an Asian-Australian person, only half-jokingly, that 9-11 was the best thing to happen to us, when the focus of Australian xenophobia was displaced from Asians to the Arabs and the Muslims. It was probably no coincidence that One Nation’s anti-Asian rhetoric dried up soon after that fateful day in New York, when the sudden focus on terrorism gave then Prime Minister John Howard the opportunity to demonise asylum seekers rescued by the Norwegian freighter MV Tampa, firstly to win an election, but then to have created thereafter the perfect foil for the Coalition to revive the passions of the electorate at the pointy end of each election cycle.

The first time I watched Romper Stomper was in 1999. I was sharing a house in the Perth suburb of Mount Lawley with my then girlfriend and an old friend from Geraldton. I remember being quietly terrified of watching it and then during it, being mortified not so much by the hate-speak of Hando and his cronies but by the brutal fight scenes between the skinheads and Vietnamese. In some ways I wish I had have gotten into a physical fight during that spring and summer of 1992, even if it meant I was on the receiving end. That’s not to say that I didn’t have enjoyable times in my adolescence but whenever I think back to those times it’s mostly the negative, racist environment that I recall. For a long time afterward, I resented have been conditioned to living in the fear of not knowing what could happen, because for a long time I went about my life terrified that something just might. But really, that’s no way for anyone to grow up in this country.