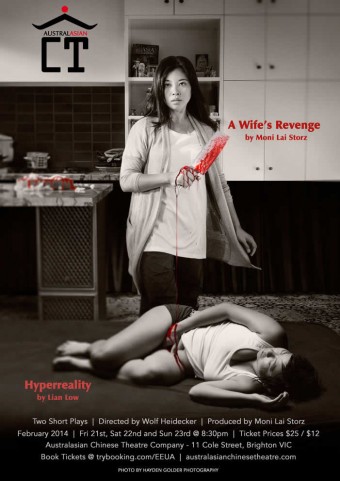

Opening this Friday 21st February for the Australasian Chinese Theatre‘s summer season are two short plays – Hyperreality by Lian Low and A Wife’s Revenge by Moni Lai Storz.

Opening this Friday 21st February for the Australasian Chinese Theatre‘s summer season are two short plays – Hyperreality by Lian Low and A Wife’s Revenge by Moni Lai Storz.

In this double bill of monologues directed by Wolf Heidecker, taking centre stage are two Chinese-Malaysian-Australi

Hyperreality was a monologue that I wrote 19 years ago, when I was just coming to terms with my lesbian sexual identity. At the time, the only training I had into a playwriting craft was a devout attention to diarising my day-to-day experiences, which I began when I was 14. At 14, I was a new migrant to Australia, and through various interpersonal interactions at school and university, I was constantly reminded of my foreigness, my un-Australianness. Writing out how I felt enabled me to make some sense about how chaotic, confused and displaced I felt. Just out of high school, through pure coincidence and reading The Age by chance, I saw an advertisement for the inaugural Irene Mitchell Inaugural Short Play Competition. I entered and in 1996, the play won the under 25 category. I was awarded $1,000 and there was a rehearsed playreading at the George Fairfax Studio, at the Victorian Arts Centre.

When it came to casting, the producers decided to fly a WAAPA based graduate actor, Fiona Choi to perform. There wasn’t anyone in Melbourne they could find.

At the time, I wasn’t ready to take on an acting role. I was just embarking into my sense of self, and I was happy to hide behind my words.

Now, two decades later, the script has undergone a re-write. Sadly, since I’d written the play, little has changed in terms of homophobic social mores – do same gender attracted couples feel safe holding hands or kissing in public? Or can a butch-looking woman walk on the street without being harassed about their gender identity, verbally or physically? While anti-discrimination laws exist, social attitudes haven’t really shifted. A recently published report “Growing up Queer“, on issues facing young Australians who are sexually diverse and gender variant found:

Almost two-thirds of the 1032 young people who completed the survey experienced some form of homophobia and/or transphobia, with some experiencing multiple forms of abuse – 64% had been verbally abused, 18% physically abused, and 32% experienced other types of homophobia and transphobia. Schools were identified as the major site in which homophobia and transphobia prevailed. Peers were most frequently the source of this homophobia and transphobia, but for many, it was the homophobia and transphobia perpetrated by some teachers that had the most profound impact in their lives.

This re-write has come about from endless discussions and meetings with a very generous director, Wolf Heidecker. Furthermore, in the re-write, there are gay family characters in the play who were always in the protagonist’s life, but she was oblivious to. In introducing the characters, Hyperreality touches on perhaps a Chinese cultural characteristic – not talking about sex or sexuality or love in family conversations. In writing this article, I’m reminded of reading Hoa Pham’s interview with Michele Lee, where Michele explains that growing up not seeing stories about Asian people’s sexuality motivated her in writing her theatre play Moths which explored Asian Australian perspectives on sexuality.

The most challenging aspect about Hyperreality is to perform the words I’d written! I don’t see myself as an actor, however the challenge was too good to pass by. As it’s a short play, I have to flesh out subtext and this is where it’s been so incredible to work with a director as generous and big-hearted as Wolf. Jumping in and being present and alive in the moment of performance is a challenge, and hopefully I’ll be able to achieve all this – as there’s no way for me to hide behind my words this time.

* * *

Moni Lai Storz is a Sociologist and a cross-cultural consultant specialising in Asian business cultures. Her love for the theatre developed early in primary school back in British Malaya. She has “acted” since then – lecturing and performing in front of corporate audiences using the tools from the theatre such as story telling and music. She founded the Australasian Chinese Theatre to provide more opportunities for Chinese Australasian performers & related theatre makers to showcase their talents. Moni’s intercultural play Our Man in Beijing enjoyed four productions in Victoria including a season at La Mama. Then it went on tour to Malaysia (a collaboration with the Kuala Lumpur Performing Arts Centre (KLPAC). Moni’s novels include Notes to Her Sisters, Heaven Has Eyes and the Yin Yang of Loving.

Moni replies to Lian Low’s questions about A Wife’s Revenge.

1. Why did you write a play titled A Wife’s Revenge? What’s the story about? (Without giving us spoilers, of course!)

I wrote A Wife’s Revenge in response to an Australian women’s theatre collective (whose name I can’t recall now) call for women‘s monologues. The story is about a Chinese Malaysian Australian woman’s betrayal by her husband. It is a common occurrence found in many different cultures, the unfaithful husband nicking off to be with a younger woman. However, I wrote the story to highlight the husband’s ingratitude. Ingratitude in the Chinese culture is not the same as in White Anglo culture. An ungrateful person is seen as not knowing how to be an appropriate human being within the Confucian value system. The husband in the play has violated something deeper than mere infidelity. He has violated not only his wife by being unfaithful but also “sinned” against Lao Tian, the Confucian/Taoist sky god. The wife character “knows” this on unconscious level. So which is hurting the wife more: the husband’s infidelity or his not knowing how to be a “human being?”

2. Have you enjoyed the writing process? How has the script developed from its inception? Tell us about the workshopping and development process that it’s undergone.

Writing has always been both a sweet and sour process so I cannot say I have enjoyed the writing of A Wife’s Revenge. Writing for me is both painful and “gainful”, hence a sweet and sour process. Agony & ecstasy. When I write, there are memories, stories told & heard, so in writing about Chinese women, I recalled the women in my life, my mother and grandmother, my sisters, etc. A Wife’s Revenge is a sort of composite derived from a lot of Chinese women’s lives, condensed into a monologue.

The script develops itself in an unconscious way. Consciously, in response to a call for monologues by this women’s collective, I sort of said to myself that it would be a good exercise as I have never written a monologue before. Having made up my mind to write one, the story sort of came to me spontaneously. In an unconscious way, almost like a dream, remembering and retrieving snippets to create a coherent piece of work.

I read it in a workshop by Alex Broun, famed for his short & sweet plays. This was in Penang, in Malaysia. My little play was well received because the workshop participants were mainly Malaysian and they understood the play. I remember how pleased I was when Faridah Merican, the founding mother of live theatre in Malaysia gave me the thumbs up sign. That was a sweet moment.

3. Why did you decide to have a season of two short plays with very different themes? Don’t you think the play is for different audiences?

When I read Hyperreality, I knew at once that it would be very meaningful to have it performed by my theatre company as it was written by a Chinese Australian girl, and its topic needs to be out there, i.e Chinese female homosexuality. I tagged A Wife’s Revenge with it because although both plays appear to be radically different and will draw different audiences, for me, the commonality in these two plays is this: it is about Chinese women’s lives. This part of our lives as Chinese women in Australia is very little known: that we do have unfaithful husbands and that our daughters can be lesbians but there is little portrayed in Australia about these aspects of our lives in theatre. Guess in some way I want to shatter the stereotype of us as Chinese women. A more practical reason is that once I decided to produce Hyperreality, I needed another short play to go with it to make the evening long enough to justify people coming to see it and charge them for it.

4.Can you tell us about why you founded the Australasian Chinese Theatre?

I founded the ACT because there were so few opportunities for Chinese Australians to perform. The ACT hopes to provide opportunities for Chinese Australasian performing artists to be more visible. I guess when I went to Monash University as a student in 1966, my love of live theatre that was kindled as a school girl in British Malaya, was sadly crushed when it was quickly brought home to me that in Australia, I would not be able to perform. Who would cast a Malaysian Chinese girl in the role of Medea or Shakespeare’s Juliet? Maybe in the Good Woman of Szezuan and even in that, I saw a White Anglo woman playing the Chinese woman. Have things changed since 1966? Sadly,very little. Hence, it is a case of: if you can’t beat them, don’t join them, create your own.

5. What are your future plans for the Australasian Chinese Theatre?

One of the more immediate plans is to pull more Chinese Australians and Kiwis into the orbit of the ACT whether as performing artists or writers, story tellers, directors, etc. These people will be the decision makers in relation to the future of the ACT. I have put out the invitation for Chinese Australasian theatre makers to approach me with ideas, scripts, and their hopes and dreams. So these are coming in steadily and makes me very happy. In the immediate future, we are working on some story telling workshops on the themes of being Chinese or mixed Chinese heritage in Australia. I am convinced that through these workshops, a script or two will emerge for production under the auspices of the ACT.

A Wife’s Revenge and Hyperreality is on 8:30pm, Friday 21st, Sat 22nd and Sun 23rd February at the Australasian Chinese Theatre, Brighton.

*** Lian Low is Peril’s Prose Editor.