More than Exotic: Nine ‘halfie’ women on mixed-Asian identity

If you’re an Asian person of mixed-raced, you’ve probably been asked the same thing your whole life: “Where are you from?” “What’s your mix?” “How is your English so good?” “Why do you sound different to other Asians I’ve met?” Same shit, different stank. To us, all these questions mean the same thing, and each is loaded with a white person’s world of assumption.

There’s also a good chance you’ve been asked these questions in the same way by the same people: friends-of-friends, co-workers, tourists, locals, men in bars, women in bars, shop assistants, your neighbourhood dog beautician. Strangers.

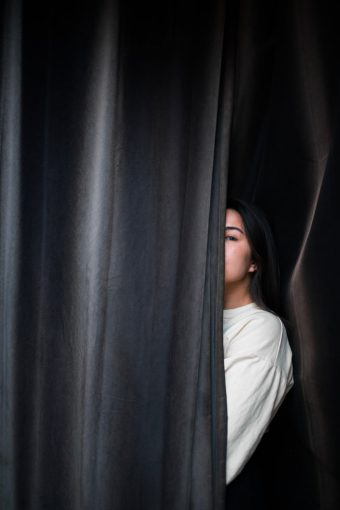

They chase you. Lean over you. Tap your shoulder. All to indulge their curiosity, stroke their ego with one spin of the ethnic wheel of fortune.

After years of hearing “Where are you from?”, I’m tired.

Here. I’m from here.

Confident strangers believing they have the right enquire about my Asianness spells out a daunting power dynamic. In these situations I’m reduced to being the ‘other’, and it’s isolating as hell. There’s apparently something about one’s perceived exoticism that suddenly opens them up as a public spectacle, as fair game.

Sometimes I resort to my own little tricks.

One of my favourite ways of dealing with nosy strangers is with ‘The Muttbutt’ method. “Oh, my mix? Sure! I’m quarter Borzoi, quarter Tibetan Mastiff and half Pitbull.” The Muttbutt was my own way of snatching back some of the power. Nora Ephron said, “Everything is copy,”—meaning you make situations what you want them to be, rewriting yourself out of being the butt of the joke. In The Muttbutt, you can bet the stranger will usually nod in firm agreement—so taken by their new yet fleeting connection to the exotic they haven’t even realised I’ve been listing dog breeds.

I know I shouldn’t have to make jokes all the time. And I shouldn’t have to keep telling strangers where the heck I’m from. Yet being mixed-race means people will always doubt the legitimacy of your racial identities, trying to decide whether they deem them real or enough.

When you ask a mixed-race person where they’re “really from” you’re telling them they don’t belong. This denial of race leads to issues of identity. Above all, it’s isolating and othering.

On Instagram I remember commenting on a racist meme, calling out its awful punchline. In turn, I received the response: “Sweetie why are you mad? You’re the one with the white girl privilege.”

Sometimes I fall into patterns of thinking that, because I’m half-white and have been raised in a predominately white society, I can’t really identify as a person of colour. It’s taken a while, but I’ve learned that the idea of races being mutually exclusive is a myth. Having one race, or aligning with one particular race as a mixed-race person, should not diminish the legitimacy of your other races. Your whiteness does not cancel out your diversity.

I know I’m not alone here. A few weeks ago, I wondered about the other mixed-race Asians around me. Do they bear the same weight of having a face of both the familiar and faraway land? And what is it to be constantly reminded of this?

So, I’ve done what I know best: opened it up to the floor. The floor of the semi-Asian sisterhood. The Eurasian Invasion. The mixed bag. Ok, I’ll stop.

At first I felt hypocritical about asking other mixed-race Asian women to tidy their stories into a few paragraphs. Isn’t this what they’ve been asked to do their whole lives? To put themselves into a box and define what they are, and fast? But once my inbox started filling up with responses, I noticed that the theme of internalised isolation—of being asked to pick one race—ran deep.

I hope this helps start a two-way conversation, rather than one that only hinges on “Where are you from?”

Victoria Blom 24, freelance artist, instagram.com/daraneerat

Growing up in a half-Thai, half-Swedish family in the smallest city of Sweden, surrounded by forest and nothing but forest, had both its ups and its downs. I was taught to eat spicy food, as well as how to make moose meatballs.

But in school, I was typically classified as “the brown girl”. My schoolmates couldn’t place me in a typical category—I was so different to everyone else. I wasn’t white, black, Asian or adopted. I was something in between all of that.

That feeling of not having an identity hung over me until I finished school and my mom made me move to Bangkok, Thailand. I was 18. There, I met loads of other ‘halfies’. I felt like I had finally found my clique.

Yet it doesn’t matter if I’m in Thailand, Sweden or anywhere else in the world, because the locals still don’t see me as one of them. And that’s why I’m lucky to have made friends from all around the globe who makes me feel at home.

I’m happy to be what I am today. My mixed experience has taught me respect, and awareness of other cultures. I feel unique, and I’m grateful for that now. I’m a Viking with a tan.

Breanna Espina 24, entrepreneur/mother, instagram.com/breannaespina

I grew up in a small town on the far South Coast. Rural Australia. I lived in a predominantly Caucasian neighbourhood as half-Filipino and half-Australian, which meant feeling those insecurities of being and looking different to my peers. Fortunately, being Filipino brought a culture into my life that most others around me didn’t get to experience.

Every weekend at least 20 Filipino families within an hour’s distance would travel and gather at a family’s house. Our mothers would sing and pray to the Mother Mary statue—an effigy that would rotate weekly to another Filipino family who would host the next celebration—and the kids would play, bonding like cousins growing up together in our own tight-knit community. It was an exciting, food-filled fiesta every weekend.

Being surrounded by this fun, karaoke-singing and dancing culture was the experience of my heritage every week. It gave me the confidence to be secure on the topic of race at such a young age. It means I rarely doubt my differences, and am proud to embrace them.

Nikita Lazaroo 21, psychology student

I don’t think I truly realised my ‘Eurasian-ness’ until I was fourteen. Of course, I wasn’t naïve to the fact that mum was Australian, dad was Malaysian, and my sister and I were a bit of both. But for most of my childhood being Eurasian just meant going on fun and sweaty holidays to Malaysia, getting to eat an amazing variety of foods and achieving the perfect tan. I grew up in international schools in Tokyo and Hong Kong, where being mixed-race was normal, and having some sort of Asian heritage made me fit in that little bit more.

It wasn’t before moving to America at the age of fourteen that the meaning of Eurasian changed for me. I moved to a predominantly white, all-girls school. Most students had never been abroad, much less lived in a foreign country. I don’t want to put all of my former classmates in one basket (in a country as racially-charged as America, there are some girls I went to school with who will know more about discrimination than I ever will), but on the whole I felt that my background separated me from them, and I never quite felt like I belonged there.

Maybe it was because when my family moved to America I was older, and so more observant, but from that point I began to notice other things that were a direct result of mine and my parents’ ethnicities. I noticed the extra bit of attention my dad received at the airport, and how it took everyone a moment before they realised I was his daughter and my mum his wife. I also noticed the attention I started to get as I got older. I started to hear that I was ‘exotic’—a word that still makes me cringe. At fourteen, being Eurasian became something that made me different, and it’s taken me a while to realise that this definitely isn’t a bad thing.

I still hate it when people (men) are fascinated by where I’m from, or why my nationality isn’t clear from my appearance. More than that, I hate hearing, “Oh, but where are you really from?” or “Wow! You don’t sound Australian.” To be honest, I don’t feel like I’m from anywhere—it’s complicated and I’m still a little insecure about it. But if I give you an answer—listen to me! I know where I’m from more than you do.

Having said this, as I get older, I am increasingly more aware of the benefits of being a Eurasian-TCK (third culture kid). I love that I am able to go anywhere and make myself at home, that I can try new foods or experiences without fear, and that I can usually find something in common with anyone. I like to think that my background and upbringing has made me an open-minded and independent person. I’m incredibly grateful that my Aussie mum and Malaysian dad shacked up and decided to raise me and my sister abroad. So cheers to you, mum and dad.

Emily Ember 23, art teacher/photographer, instagram.com/emilyember

I was born in Hong Kong to a Taiwanese mother and an English father. Growing up I could never fully identify with just one culture or race. My parents were of the mind that being different is what makes life interesting.

Though I feel inherently British, I feel a strong affiliation with my Asian heritage and have spent a lot of my adult life rediscovering these roots.

I feel most at peace when exploring new countries and cultures, never belonging here nor there, to this race or that race. For me, it has been a blessing as I find home wherever life takes me.

Kelley Day 21, actress, instagram.com/itskelleyday

When I was speaking to someone a few weeks ago about my life story, I was told that I was a ‘TCK’. Confused, I asked, “What on earth does that mean?”

A third culture kid is someone who has grown up in a culture different to either of their parents’. I was relieved that finally there was a classification for this type of situation, because it saves me from the long explanation that I’m used to when introducing myself!

Being half-Filipina, half-British, born and raised in Dubai, and now living and working in the Philippines, I can say I’ve had a cocktail of experiences. I suppose what first comes to mind are the bad ones.

Filipinos form 21% of Dubai’s population, with the vast majority being OFWs (Overseas Foreign Workers). These OFWs are stereotypically placed into labour duty, working jobs as the domestic help, toilet cleaners, school bus conductors, or otherwise working at fast-food chains. In the International, British-curriculum school I attended, I knew only two Filipinos—and we were both mixed-race—who were current students.

No matter how much I would try highlight my British heritage and conceal my Filipino one, I experienced constant bullying. Students would say bad things about me and my mum, and when it came to parent–teacher meetings, the other students made clear their disbelief of the fact that my dad was actually white, speculating instead that perhaps I was adopted.

One time, during a moment I was being trash-talked about my Filipino culture, someone pulled my school trousers down in front of everyone to ‘prove’ that their culture overpowered mine. I was fifteen years old. I soon learned that if I stopped showing that I cared, the bullying would fade.

Admittedly, the discrimination I’d encounter would almost make me feel ashamed of my Filipino culture.

Nevertheless, after a long day at school, I would come home to a lovely house filled with the aroma of Sinigang or Adobo, my favourite Filipino dishes. I would indulge in these foods and not think again about the hurtful words of the other students.

I would watch TV with my mum in the evening and sing along with the programs that would show on TFC (The Filipino Channel), enjoying the light-hearted humour and the talented singing voices that run in Filipino blood.

I would spend family holidays in my mum’s province, Tarlac (just a couple of hours north of Manila), and run around and play with my relatives in the street, learning to enjoy the simple pleasures of a simple life. We would have big feasts in the evenings, with the food coming straight from the farms that my relatives harvested. They would cook only the best Sinigang and Adobo for me, and we would sing karaoke until sunrise.

The reality is, I was too afraid to speak up and tell the kids at my school that I was, in fact, extremely proud to be Filipina. I was too afraid to tell them that we are so much more than our stereotype. When I made the decision at eighteen years old to skip university in England and move to the Philippines, I was too afraid to tell my friends that it was a move I was excited about.

It has now been two and a half years since I moved to the Philippines. I’ve been studying Tagalog—I never learned it growing up—and I am now an Artista (a public figure/celebrity), appearing on the shows I used to watch with my mum! I have been learning and adapting more each day to Filipino culture, and now I couldn’t be happier with the person I’ve become.

I went back to Dubai for a reunion with my classmates and, if I am totally honest, no one bullied me for a second. I told them about my journey, my new career, my experiences, and how much I love my new life in the Philippines. I could tell that they were somewhat envious of the fascinating life I delved into after we all graduated.

Nowadays, it turns out the Philippines is now widely-known as an absolute paradise for vacations. Thanks to social media and vlogging, travelling is becoming the ‘in’ thing, and the Philippine Islands never fail to reach top ranks in the many travel destination lists. This only adds to my Filipino pride.

I am also truly grateful for my British side. It’s no secret that the Philippines has a thing for ‘halfies’, particularly in the industry I work in. I have my dad’s height, and some of his facial features, and it makes me look different to other Filipinos, yet it’s obvious that I’m Filipino too.

I cherish my mixed culture. I love that I grew up indulging in my British side, and now I’m indulging in my Filipino side. I love how my bad experiences in school only made me stronger and more confident about my mixed culture. I love who I am today.

Steffie Harner 26, digital marketer, instagram.com/steffieharner

Half-Filipina, quarter-Korean, quarter-German born in Albuquerque, New Mexico. To grow up mixed is be in a constant identity crisis. I used to hate being multiethnic. I was ‘too white’ to be Asian, ‘too Asian’ to be white. After high school, with the advent of social media, I started to connect with other mixed people and finally came to embrace my unique roots. Though, culturally, I will always consider myself very Filipina-American. I am who I am, and I am proud of that.

Juria Hartmans 26, actor/model, instagram.com/milkshakesspeare/

Growing up in Asia, I felt like I didn’t really fit in because I didn’t identify with any specific culture. My mother is Asian and my father, Caucasian. I had a lot of internal conflict with the cultural environment I was living in. In my early years, I never felt truly accepted by the people around me. On many occasions, I was also put down for the way I look. Instead of being a cheerleader, I was told that I was ‘more mascot material’. I can laugh about it now, but back then it was hurtful.

My view is that the community in Asia tends to be more collectivistic, and I felt pressured to conform to the societal dos and don’ts. I was indirectly forced to follow the rules of a religion that I questioned from the beginning. It was made clear to me that questioning your religion will give you an all-expense paid trip to hell and, as a kid, I never wanted that! Where I grew up, race and religion were heavily intertwined, so being bad at your religion also made you bad at being your race. I was never allowed to even contemplate following a religion or a culture outside of my eastern roots. It just wasn’t an option.

But it wasn’t all bad. It shaped me into who I am. As an adult, I hit a point in my life where I realised that you are allowed to question who you are and what you stand for. My race does not define me or my beliefs. I strongly believe that race and religion should be able to exist independently of each other. I read a book recently by Mark Manson called The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck, and there is one sentence in there that I truly identify with: “Not giving a fuck does not mean being indifferent; it means being comfortable with being different.” So, here I stand today, not giving a fuck about how ethnicity should define me. I’m just celebrating being different and not fitting in!

Celeste Matthews 23, law student, instagram.com/celestebee

Trying to explain to your third-grade classmates the ‘mysterious’ lunch your Chinese mom packed for you (Chinese sausage mixed in with stuffing from Thanksgiving); drunk men cat-calling “ni hao”; receiving a fork instead of chopsticks at your local Chinese restaurant. These are just a handful of my experiences growing up as a mixed-race woman in Canada. My mother is Chinese, and my father is white. “What kind of white?” I hear this all the time. Technically, I’m a mix of English, Scottish, Irish, French, Spanish, and Welsh, but I was born and raised in Canada, which is why I just say “white.” It took me years to realise just how lucky I am to be mixed-race, or, as my parents would say, “the best of the East and the West.” But my journey to self-discovery was a long and tumultuous one.

Ask any ethnic kid what their childhood was like and they’ll almost certainly say that, at one point, they wished they were white—or at least looked white. I remember begging my mom to let me dye my dark brown hair blonde when I was eight, and throwing a fit when we would go to yet another Chinese restaurant instead of the local pizza joint (crazy, right?!). I remember being embarrassed to wear my qi pao to school on our World Culture Day, and refusing to learn Mandarin instead of French.

I used to hate it when people would say I looked more Chinese than white. As shameful as it is to admit, it took me years of learning and acceptance before I was finally proud to be mixed-race. Growing up mixed is honestly such a unique experience, and you really can’t understand it unless you know what it’s like first hand.

The fetishisation of mixed-race Asians is so prominent. Countless people—both white and Asian—have told me (and continue to tell me) how they can’t wait to marry X race because they want mixed babies. It’s an unsettling feeling to literally be a prototype for some stranger’s future spawn, but even my own mother exoticises me, constantly telling me how I look “so much more exotic” than her.

Dating is a whole other nightmare. It’s as though I, as a person, don’t actually exist to men—only my looks. I can’t tell you the number of times that I’ve been asked “What are you?” before they even bother to ask my name. My personal favourite is when I was dating a Chinese guy and he said to me, “Too bad our kids would only be one quarter-white.” People will ask my white friends what their names are, and then they’ll turn to me and ask, “And you? Where are you from?” I was surprised to discover the comments I received while living in Hong Kong, where one of my co-workers remarked, “You’re not even Chinese,” because I didn’t speak Cantonese.

Despite it all, I would never change anything about being mixed. Growing up bi-racial has given me a unique perspective on life and I’m so glad that I’ve come to love my multi-racial identity.

Megumi Tanaka 27, musician, instagram.com/meewgumi/

Growing up, kids asked if I felt more American or Japanese. At first, I said both, beaming with pride. But they insisted I choose one. I felt like they singled me out for looking different, so I changed my answer to Japanese. I gave a binary answer to a multifaceted question. Being mixed means that you’re a sum that’s greater than your parts, it means you’re inseparable from your unique cultural heritage. When the world asks you to limit yourself, it means you have much to teach them.

I’m An 8th generation Eurasian from Malaysia, migrated to Australia in 1980 was 5 years old. Since World War Two my kind of ‘Eurasianess’ no longer exists in south East Asia, we no longer have our communities anymore, many marrying full Blooded asians or full Blooded Caucasians to fit in. I now live in Australia and am always mistaken as being Italian or Greek. I’m always ‘other’ and I’m constantly treated as ‘other’. Here in Australia, you’re not Australian unless you’re white- in a young white settlement that relies on non white immigrant labour, it’s insulting and most definitely creates the divide of who belongs and who doesn’t. You see this daily on how people interact with you. People need to put you in a box so my response To them is: create a new box sunshine. If I had my own community of eurasians like the Greeks, Italians, Vietnamese, Chinese etc, I probably wouldn’t feel so alone but us Eurasians are a very heterogenous group. The world is small and life is short. Find your people and it’s not always along racial lines.