The story of watercolour artist and Aranda tribesperson, Albert Namatjira, is a striking example of the kind of indignities non-Indigenous Australians continue to inflict on First Australians. Through masterful storytelling and liberal use of actual footage from his lifetime, Namatjira Project details, not only the life of Albert Namatjira himself, but also that of the generations of artists within his family following him.

The Namatjira Project itself launched in 2009, and was developed by BigHart with the Namatjira family. It primarily revolves around the performance of Namatjira onstage, a play about Albert’s rise to fame and subsequent disappointments. It was described by theatre critic, John McCallum as depicting ‘the commercial appropriation of Aboriginal experience’. The aim of the Project is ultimately to garner support from the community at large to buy back the copyright of Albert Namatjira’s work, which through legal loopholes is now in the hands of a (white) private investor.

In its essence, the documentary similarly functions as a vehicle to further advocate justice for the Namatjira family, as we see that Albert’s descendants are forced to work within a complex and alien cultural framework, in order to reclaim something which should never have left their hands. We see the development of the play, and its warm reception from Namatjira’s home community to its nationwide tour (of mainly white audiences). We watch it culminate in a London exhibition, and an audience with the Queen of England. Finally, we discover that, despite the critical success of the Namatjira Project, the living conditions of the family are still miserable, and the copyright still rests with the same investor – almost ten years after the Project’s launch.

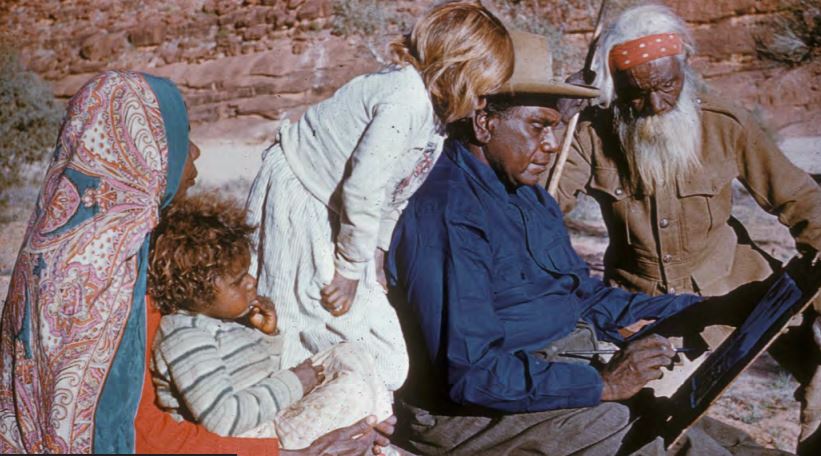

Kevin Namatjira and Lenie Namatjira are two of Albert’s grandchildren. Both painters, in their grandfather’s tradition, they are recurring figures in the documentary, discussing their grandfather’s work, and working hard to support the Project, including going on tour to hold pre-show workshops on painting watercolour Australian landscapes. The backdrop of the film is the development and touring of Namatjira onstage, a theatre production written and directed by Scott Rankin, starring the familial and charismatic Trevor Jamieson and Derik Lynch. However, the eye is drawn irresistibly back to these two elders and their quest for justice.

Namatjira Project seems to be a story about language, as much as it is about art; more specifically the power of the “right” language and cultural framework; The Aranda people, to which the Namatjiras belong predominantly speak Western Arrernte, English is not necessarily their first language. When we see the people from their community speaking amongst themselves, they do not use English. The English they do speak appears to be functional, more so than what would be considered “correct English”. Relatively,the use of subtitles offered within the film do not seek to ‘correct mistakes’ of the speaker, instead, the words are printed in the same way they’ve been spoken. This works to offer a type of dignity to the cadence of the spoken English of the Aranda people,. However the use of subtitles, in themselves, also highlights the way in which language contributes to the Namatjiras’ continuing plight.

Kevin Namatjira is a man of very, very few words. When he does speak it is very slow, and there seem to be layers left unspoken beneath his chosen words. Talking about his involvement in painting the backdrops for Namatjira as a tribute to his grandfather, Kevin says “I… feel a little bit alright, little bit shame.” He doesn’t expand upon this admission of shame. When asked to comment on the pre-show painting workshops he and Lenie hold, he admits that he feels the people around him “talk too much”, and it makes him nervous. Yet Namatjira Project shows us that as Aranda Elders in the spotlight, there is a great expectation placed on both Kevin and Lenie to assert the rights of their people and bring about a turning point in their lives, and to do this they need to function in a Western colonial context, and work within its system, using its language; aspects in which their experiences are restricted .

This is most exemplified while the two of them are in London, for an exhibition in which their grandfather’s work takes center stage. Scott Rankin, director of Namatjira onstage, pulls Kevin aside at one point to make sure he knows that when The Guardian (newspaper) interviews him, it will be an opportunity to speak his mind, and actually be ‘heard by the people in power back in Australia’. Rankin, a white man, navigates this world with ease, and attempts to guide the Namatjiras through it with him. As they later prepare for an audience with the Queen, Kevin says he wants to ask her if the queen can help him get secure housing and land. He says he thinks she can help him with this because the police that may take his housing away “got Queen’s crown” in their helmets and badges. In a television interview following the meeting, the interviewer asks him what he hopes will come from this, Kevin speaks slowly and little, just as he always does. In a culture where rhetoric and emotional appeals abound, it doesn’t feel like enough.

The life of Albert Namatjira, the Namatjira Project itself, and the documentary Namatjira Project, all seem to be fundamentally about First Australians straddling the Western colonial world and making sacrifices in order to live as they always have, and to secure future prospects for their children. Lenie and her family emphasise their desire for the return of the copyright “to make the family proud… for our future”. It is not just about the money, nor even the principle of the unfairness. In a community where “family’s everything”, the Namatjiras are fighting for the return of their family’s dignity.

The Namatjiras are still negotiating to buy back the copyright they never sold. You can support them by going to www.namatjiratrust.org

or

to apply to host a screening of Namatjira Project documentary, visit www.namatjiradocumentary.org/

The Namatjira Project featured as part of this years Brisbane Film Festival.