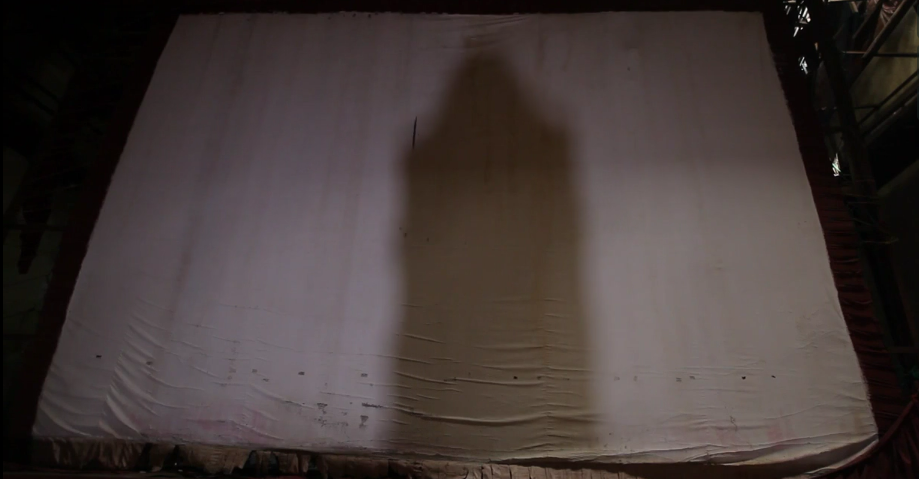

The surreal orange creature stares curiously up at its own shadow projected on the tattered cinema screen, from where it sits in the rundown art deco seating. The atmosphere is still with the faint sound of chanting from a nearby pagoda and echoes of children’s voices can be heard ricocheting around the desolate space. The light through the broken ceiling illuminates the face of the creature. A spiritual moment of recognitions and non–recognition is happening as it meets itself on the screen.

The creature is the The Buddhist Bug (2009-), a performance and character that Ali has developed over a number of years, and is maybe the gentlest creation in the artist’s repertoire though has had varying reactions depending on the context. Calling herself a ‘Global Agitator’ amongst other things, Ali’s background in political activism informs the strategies of her practice. Her characters and work find challenging ways to be in dialogue about religious intolerance, difference and otherness in a world that is becoming smaller.

The bug is a curious creature, with a transnational identity and is somewhat autobiographical. The artist was born in 1974 to a Muslim Khmer family in Battambang, Cambodia, the second largest city in the nation with a sprawling rural nature. The family fled the war, which started in 1979, living in a refugee camp in Thailand, then staying in Malaysia with family and finally settling in the United States in Chicago. Ali has visited Cambodia many times since 2004 onwards, engaging with local artists and eventually returning to live in Phnom Penh from 2011 to 2015, which is when the bug made its journey through Cambodia. Hybrid in nature, s/he (genderless according to the artist) references Buddhism in the saffron coloured skin like the robes of Khmer monks and Islam in her modest hijab headdress. Surreal in scale (extending up to 100 metres at times), the bug is often childlike in her exploration of spaces and environments. As a body of work, The Buddhist Bug takes the form of live performances, video art and staged photographs, negotiating with the people and places s/he encounters. These encounters often have moments of resonance in what these ecosystems project upon her as s/he explores her personal identity.

For APT8 Ali finished the bug’s journey through Cambodia in the commission The Buddhist Bug, Into the Night (2015). The Old Cinema (2014), is an earlier work in the series, described in the introduction above. It was shot in the artist’s place of birth, Battambang. It is pivotal marker in its narrative. Set in the dilapidated art deco cinema, Golden Temple, it makes reference to what was known at ‘the golden era’ of Cambodian cinema. A time which peaked just before the Khmer Rouge took over the country, resulting in (amongst other things) the dismantling and all most total genocide of the intellectual and creative class. The period is looked back on fondly by a younger generation of artists today, a ghost of a not so distant past. The Old Cinema (2014) can be seen as the pinnacle of the Buddhist Bug’s pilgrimage to identity to find physical it’s ‘otherness’, and perhaps to find it is not fixed nor tangible, a falsehood. S/he finds an empty-ness, a lost glorious past and finally a shadow of herself/himself.

The work also recalls Plato’s allegory of the cave from his book the Republic[1]. In the story, told through a discussion between two brothers, a group of people are shackled in a cave facing a wall. Their only stimulus are the shadows projected on the wall created by their captors and cast by objects held in front of a fire. They come to identify with shadows giving them names and ultimately deeming them their reality. One prisoner escapes, eyes burning from his first experience of sunlight, then to see ‘real’ objects and ‘real’ people. He comes to understand the shadows were not reality. This allegory sometimes referred to as the first notion of cinema; resonate with the Buddhist Bug’s ongoing journey navigating the projections she cast and projections cast upon her in the world. How do other people see her? How does s/he see herself/himself? The site being a cinema is no accident. We can think about in this time of hysteria, how Muslim and ‘other’ non-white identities are represented in western mainstream media, how polarizing the hijab, as well as other faith based headdresses have become. However, through the bug, the artist softens, makes surreal and sweet this encounter with ‘otherness’.

We saw this realised during the two performances of the Buddhist Bug during the APT8 live program, performed in two spaces at QAGOMA, first at the Water Mall, and later at Bodhi Tree Garden. At the Bodhi Tree Garden the encounter was far more playful. The bug’s body set at a low height allowing children dominated the situation. The bug was as curious as the children. It was a playground encounter of sorts. The kids coy at first, slowly gaining more confidence coming closer to inspect and offer her grass to eat. The bug thoughtfully declined.

In the Water Mall performance the bug was situated under by Haegue Yang’s installation Sol LeWitt Upside Down – Structure with Three Towers, Expanded 23 Times (2015), almost forming an inverted chandelier around the bugs coiled form. This perhaps informed a rather regal atmosphere; intoning a quiet respect. The audience queued to walk on to the raised pathway to greet the bug, as s/he peering down from her slightly elevated perspective. A curious ritual began to occur. The audience began to greeting the bug with Khmer ‘sampeah’. A respectful greeting in Khmer culture where one puts their hands together, palms facing, at height comparable to the stature of who is being greeted. For example, one might hold ones hands at forehead height when greeting royalty and to a teacher, perhaps at lip height. Speaking to the artist after, Ali thought this perhaps began with a Khmer family, after which others took this cue. The bug embodied the respect s/he was given in this performance. In this the performance took on the character of a diplomatic ceremony, awkwardness in adopting a new cultural more and all.

Other works in Ali’s repertoire have also taken on a similar diplomacy, quite literally in her work in her collaborative lab, Studio Revolt’s My Asian Americana (2011), resulting in a dialogue with the White House. At the time The White House Initiative on Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders issued a video challenge, “What’s Your Story?” . A project ostensibly designed to make visible positive Asian and Pacific Islander stories. Ali and her collaborative partner Masahiro Sugano had been engaging with deported Cambodian Americans in Phnom Penh since their arrival in the country. The deportees had been forcibly moved to Cambodia (some having never been there before, born in refugee camps on the Thai side of the border) under a new government policy that saw these ‘undesirables returned to their ‘homelands’ post jail-terms in the States. Some were being picked up and deported years after their release from prison, many with wives and children. Sugano writes, ‘(the) deportations operate as additional punishment for people who have already served their time, often (for) mistakes made in their youth. Deportations create more traumas within an already scarred refugee community by severing relationships and breaking up families. Current immigration laws are the most anti-immigrant in all of U.S. history.’[2]

With this Studio Revolt decided to use the What’s Your Story? Challenge to highlight this rather unsavoury Asian American narrative. Their video highlighted the deportee’s American-ness, with participants declaring their allegiance to the United States of America in various locations across Phnom Penh, sharing their stories of growing up in America. The winner of the challenge, it was suggested, would be decided by popular vote and would be awarded with the opportunity to bring their issue in person to the Champions of Change event at the White House. The views of their video skyrocket, above the other submissions, but strangely they were not announced the winners. Key to this was their participants and collaborators in My Asian Americana, by law, would be unable to attend a ceremony in the states and the critique of government policy that the video posed was something that would be best uncelebrated.

After some dialogue with the concerned White House public servants, Studio Revolt, frustrated with the hypocrisy of what one would hope would be a democratic process, created their own awards ceremony called Champions of Change, Too. With representatives from the Cambodian royal family, the deportee and Phnom Penh art community attending the event, ‘Exiled Americans’ stories were shared and celebrated at Javaarts in 2012. This was a calculated act of defiance, with official insignia and all the ribbon and bows of a ‘state’ ceremony.

Never to shy away from the political and divisive Ali’s work is responsive. This, evident in her newest creation The Red Chador (2015 -). Once again using religious aesthetic, Ali forges a solo diplomatic effort with various publics. Creating a majestic figure in a flowing sequined full body headdress (chador), Ali’s Red Chador made her first appearance in Paris as part of a commissioned by the Palais de Tokyo for their Secret Archipelago (2015) exhibition.

Realised in two parts, the first, a mute public invention where the figure followed a thoughtful path through the streets of Paris, through migrant areas and iconic spaces including the park below the Eiffel Tower. In this new body of work, in Paris, she tackles islamophobia at a decidedly sensitive time, just three months after the shooting at offices of French satirical weekly newspaper, Charlie Hebdo, which resulted in the death of 12 staff members. According to the artist she received a caring, almost paternal response, with the public rallying around her in protection and care, not dissimilar to the outpouring of support, after the shooting at Lindt Coffee shop in Sydney Australia, exemplified by the #illridewithyou twitter hashtag which encouraged the protection women wearing the hijab on public transport.

The second part of the Red Chador work in Paris, Beheadings (2015), was performed inside the Palais de Tokyo museum. For this 12 hour durational performance, Ali was set up in the red chador regalia, at a table with a pile of white baguettes. From there she issued her demands. If each demand was not met on the hour a baguette would be ‘beheaded’. These sometimes impossible, comedic and pointed demands included ‘bring me the smile of the Mona Lisa’, ‘bring me 99 virgins’ and ‘bring me all the flags from the former French colonies’.

“There was this incredible moment that happened at the end of the event. My demand was to fill the room with non-white people.”[3] said Ali. “In doing so, they were forced to question people about their identity.” In attempt to fill the demand, a group of ‘non-white’ people banded around Ali in circle holding hands. “In the end, these people saved the last baguette and the whole room erupted into applause”[4], said the artist.

It is a complex and layered history that Ali is drawing on whilst playing the role of executioner. Colonial legacies, long histories of persecution and of migration are alluded to in her absurd demands. With humour she negotiates these, engaging her audiences in a dialogue that involves self-reflexivity; questioning who they are, what defines them, their privileges, their marginalization and their duty of care to others. This is a practice that can be seen as something akin to aspirational diplomacy, moving beyond the base and the binary of religion and difference as represented in mainstream media. The modern Plato’s Cave could be the cinema, television and viral videos: Plato might argue one must break free from the shackles of media and go out in the sun to understand oneself in the encounter with ‘real’ dynamic and layered world. Ali’s work does this, finding challenging ways to be in dialogue about ‘otherness’, destabilizing power structures through participation and surrealist contact.

[1] Plato’s the republic, Plato; Benjamin Jowett, New York : The Modern library, [1941]

[2] MY ASIAN AMERICANA (2011), http://studio-revolt.com/?p=305, accessed 27/03/16.

[3] [4] Anida Yoeu Ali quoted in: The Worm Turns, The Magazine, Bangkok Post, Issue 22, 2015, pg 48.