This is part 2 of “It Could Happen to Me”… For part 1, please click here.

***

Deportation did not stop with the official end of the White Australia Policy in 1973. In fact, in recent years it has increased. Today, Australia has one of the highest rates of deportation in proportion to population in the world, deporting 11,705 people between July 2014 and June 2015 and about 10,000 annually through the 2000s.[1]

Deportation disproportionately affects people who are vulnerable and have comparatively low socio-economic status. Hong Ung, who arrived in Australia age 10 with his family in 1981 is an example. His family were refugees fleeing from the Khmer Rouge genocide in Cambodia. His parents worked hard, including night shifts, leaving Hong with a family friend and he became involved with people who introduced him to drugs. He was convicted of minor, mainly drug-related offences and lived in Australia for 35 years. He requires treatment for prostate cancer but was deported in 2016 and is now in Cambodia “sleeping on the streets.” The act of deporting people like Hong Ung, also highlights the Australian government’s (lack of) responsibility, for long-term residents who have problems.

This brings us to the question of human rights which entered the public discussions around deportation in the 1960s. Willie Wong had been in Australia for eight years when he was found working without papers at a market garden in Sydney. He had stowed away on a ship from mainland China, via Hong Kong and arrived in Australia in 1958. He was deported to Hong Kong in 1968 and from there, to mainland China. His case provoked outrage in Australia as public opinion at the time opposed the forcible return of people to countries ‘where human rights did not exist’.

Founded in 1981, the Australian Human Rights Commission energetically pursued deportation orders through the 1980s in an attempt to bring Australian laws and actions into line with international frameworks on human rights but was obstructed by the Department of Immigration. In response, the government tightened citizenship laws to exclude Australian-born children of non- citizen parents in 1986. In 2005 the Federal government argued that “it had the power to shift the criteria for Australian citizenship by legislation”.[2] This prompted High Court judge Ian Callinan to state “My citizenship is very flimsy. I am worried.”[3]

The Australian constitution gives the Commonwealth government broad powers over people it deems to be ‘aliens’ but there is no definition of ‘alien’ in the constitution, nor any definition of how people can legally belong to the Australian nation. The ‘alien’ power in the constitution, section 51 (xix), is only limited by other parts of the constitution. Prior to the creation of the Nationality and Citizenship Act 1948, people who lived in Australia were British subjects and those who were not were classed as ‘aliens’. Since 1948, the presumed meaning of ‘alien’ has been the opposite of ‘citizen’ but in recent years this has been challenged. Most legal cases which have challenged the extent of the ‘aliens’ power have failed and some of the potential limitations to its powers have yet to be tested in court. We know from the 2005 Ames case in the High Court that it is possible for an Australian-born person who was a citizen to have that citizenship taken away indicating that “citizenship in itself does not confer full membership of the Australian community.” The decision also had implications for the legal position of dual nationals.

We don’t yet know the full extent of the applications of the Australian Citizenship Amendment (Allegiance to Australia Act) 2015 which can strip dual citizens of Australian citizenship. This can be done outside the legal process with police, intelligence officers and public servants making up a Citizens Loss Board that decides if a dual national has committed terrorist act and thus, should be stripped of Australian citizenship. Once a person is classed as an ‘alien’, it is mandatory to detain and deport them.

These ‘alien’ powers in the constitution enable the inhumane conditions of Australian detention centres. They enable boat turn backs such as that of the 238 people on the SIEV 5 (Harapan Indah) in 2001, the first asylum-seeker vessel to be turned back to Indonesia despite protests of those on board. The day that SIEV 5 was ‘turned back’ the SIEV X sank and 353 people drowned in international waters near Java.

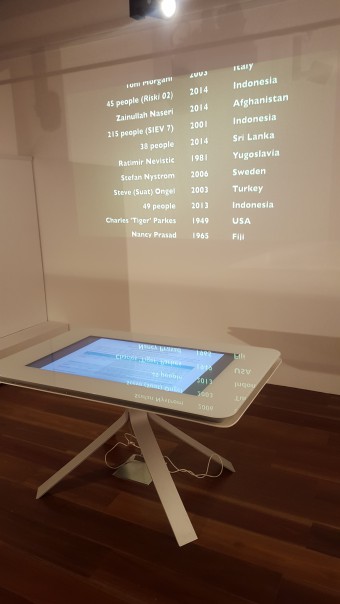

Likewise, these ‘alien’ powers enable the return of rejected asylum seekers to the places they are fleeing from. Between 2014 and 2016 it is known that four people from the Hazara ethnic group, persecuted in Afghanistan, had their applications for refugee status rejected and were deported to Afghanistan. The Refugee Review Tribunal said that it “did not believe Hazaras would be persecuted for seeking asylum in the west.” None of these people have remained in Afghanistan. Zainullah Nasri, whose refugee application was also rejected, was deported to Afghanistan in 2014 where he was “tortured by the Taliban.” In 2015, 46 Vietnamese asylum seekers who had fled on a boat were ‘taken-back’, meaning that they were directly handed over to Vietnamese authorities. Four of them have since been jailed.

Responses to exclusion

People who have been ‘alienated’ by the state often protest and resist their oppression and at times, will assist each other. British colonisation of the Australian continent from 1788 began a process of violent dispossession of Indigenous Australians from their lands and the ‘frontier wars’ between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples continued into the twentieth century. However, during the 1950s until the early 1970s, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians collaborated in campaigns for Indigenous rights and redress for injustices committed in the building of the Australian state.

It was during this period that seven year old Nancy Prasad became the centre of Australia’s first airport deportation protest in 1965. Nancy’s parents had been deported to Fiji in 1963, but she had been too ill to travel so she remained in Australia with relatives. They requested that she be allowed to stay permanently. With the co-operation of Nancy’s relatives, Charles Perkins, a prominent Aboriginal civil rights activist, kidnapped her at the airport in front of the media. After a few hours, he returned her to her relatives. Perkins said:

“I feel very strongly about it personally because it’s a colour question. Nancy is being deported because of one criterion alone and that’s colour and that’s bad and immoral as far as I am concerned.”

While she was deported the next day, Perkin’s actions were popular with anti-racism activists and helped spur the formal end of the White Australia Policy. In 1973, the Minister for Immigration Al Grassby granted permission for Nancy and her family to return, which they did.

Today, connections continue to be made between Aboriginal people and non-white migrants that Australia excludes, such as asylum seekers. In his 2015 work titled Which Way? Mahmoud Salameh, a Palestinian refugee from Syria, who was detained for 17 months in Australian detention centres, posed this question for those Australia has rejected — asylum seekers on boats and the Aboriginal people affected by the proposed closure of remote Aboriginal communities. This work was also shown in the Vessels To A Story exhibition and Salameh is continuing to work with Indigenous people through his art projects.

In 2010, it was written that

“ministers in Australia’s (Ab)Original government — with the endorsement of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy — have issued their own passports for a group of Sri Lankan asylum seekers who were refused entry to Australia.”

Indeed, RISE: Refugees, Survivors and Ex-detainees, a Melbourne-based refugee and asylum seeker support and advocacy organisation run and governed by refugees and asylum seekers, has close connections with Indigenous Australian activists, including Gurnai/Kurnai man Robbie Thorpe who gave out some of these passports.

“As settled and newly arrived refugee communities seeking protection and freedom, we acknowledge that we live on colonised land where the Indigenous peoples are the traditional owners and sovereignty was never ceded.”

On 16 July 2016, First Nations Liberation, RISE and Warriors of the Aboriginal Resistance (WAR) will hold Sovereignty + Sanctuary: A First Nations/ Refugee Solidarity Event at the State Library of Victoria, Melbourne.

http://riserefugee.org/sovereignty-sanctuary/

Vessels to A Story was organised by RISE: refugees, survivors and ex-detainees, curated by Dominic Golding, supported by the City of Melbourne and held at Library at the Dock, 107 Victoria Harbour Promenade, Docklands, 1-29 June 2016.

http://riserefugee.org/rise-arts-present-vessels-to-a-story/

***

The Asian Australian Democracy Caucus (AADC) is a non-partisan organisation. One of our ongoing commitments is to contribute a monthly blog in collaboration with Peril magazine. To find out more about this collaboration read here. If you want more information or would like to write for us, get in touch with us, Shinen Wong or Karen Schamberger at [email protected]

Please also visit us on Twitter and Facebook.

———————————————————

Further reading:

M Kartomi, The Gamelan Digul and the Prison Camp Musician Who Built It: An Australian Link with the Indonesian Revolution (University of Rochester Press, Rochester,2002).

G Nicholls, Deported: A History of Forced Departures from Australia (UNSW Press, Sydney, 2007).

Department of Immigration and Border Protection Annual Reports, https://www.border.gov.au/about/reports-publications/reports/annual

J Phillips, Boat arrivals and boat ‘turnbacks’ in Australia since 1976: a quick guide to the statistics, Parliamentary Library, Australian Parliament House, 11 September 2015,

http://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1516/Quick_Guides/BoatTurnbacks

***

[1] Nicholls, p. 167, Department of Immigration and Border Protection Annual Reports,

https://www.border.gov.au/about/reports-publications/reports/annual

[2] Nicholls, p.126.

[3] Quoted in Nicholls, p.126.