Word had it there would be a market at the festival. I was elevated, ready to kill in the dumpling line, as my empty stomach grew emptier by the second. The Adelaide night breeze felt gentle on the day I arrived, wearing a light duck-down jacket. My friends and I had just watched Regurgitator’s performance on The Velvet Underground & Nico album. Eyeing the steamy food truck menu, I was still struck by the cardboard neon signs on display, along with mahjong joints scattered around the festival centre. I found this problematic, partly due to its pale flatness without any illuminating visual charm, partly due to my resistance to this hyper-visibility of Asian kitsch in contemporary Australia.

I have a fatal weakness for dumplings. One could also argue that as a form of cultural kitsch, but I just can’t bring myself to embrace the two-dimensional cardboard neon signs indoors. A “China Town” aesthetic, saturated by a red, sinister vice, which I couldn’t stomach. But if you asked what sort of decor would be appropriate for a cultural event like this, I would be equally at a loss. Perhaps a more contemporary look and feel that could subvert the cliché? What comes immediately to mind for me are images from Blade Runner or Her, along with a sudden realisation of how my vision has been pigeonholed by a Hollywood film-scape, derived from the imagined future. Painful.

The Adelaide casino, which sits in front of the festival centre, along with the roaring from the construction site nearby, composed a metaphorical reverberation, prompting consideration to the interrelation between capital and the arts, in much the same way urban isolation has been reinforced by a heightened shield of noise from repetitive destruction and rebuilding. This reminded me of Tsai Ming-Liang’s The Wayward Cloud.

Macau Days: memory, soundscape and flavors

Artist, John Young; writer, Brian Castro; and composer and media artist, Luke Harrald, collaborated to complete Macau Days, an exhibition exploring the historical and cultural complexity of Macau as the first European settlement in Asia, during which time a city space and cultural legacy is gradually devoured by the growing casino empire.

According to Harrald, the immersive soundscape at the gallery space – rendered by the stretched sound of slot machines – is a clever manipulation and sonic embodiment of the theme that connects different mediums cohesively.

In this collective body of work, Young’s memory of an old Macau is tangled up in his abstract painting, accompanied by the use of multilingual texts. The sense of nostalgia is vivid and multi-layered. Castro captures it beautifully in his poetic writing, filling the void of “flavor”, recreating a capsule that is stuck between past and present.

There’s enough of the real

in the smell of chau-chau,

the flavor of Macau

in a glare of liquid days, mirage

of home-going not home-coming,

strolling from room to room

listening for the dinner chime.

Cocoon: A sonic odyssey back into time

Distant bells, chant, ring and ripple before slowly floating to the foreground of the theatre space, announcing the prologue of an ambitious orchestra piece that has wrapped two thousand years of history – Western Chinese landscape, religion and diverse musical form – in a continuum. As the name, Cocoon, suggests, it’s a transformation ready happen.

Composed by Melbourne based Chinese Musician, Mindy Meng Wang, and arranged and orchestrated by Jem Savage, the piece traces along the ancient silk road, with a contemporary experimental twist, offering a sonic experience fueled by festive beats, and the melancholy Guzheng, reminiscent of the passing of time like no other, and new possibilities brought by an ensemble of violin, bass trombone, saxophone, percussion, and double bass.

Wang makes a deep dive into her cultural roots, remolding familiar Chinese melodies into a complex vertex; Alternating between her two Guzheng sets at the centre of the stage, she painstakingly creates an image of a desert, enveloped by a peaceful ambience. Gentle string movements before the double base intrudes, sinking in like raindrops, damping the sandy surface. When the percussion joins in, a violent sandstorm is gradually forming, thunder and wind, violin with bass trombone, vivid and unwavering. Then she reverts to the strong bowing sequence to echo the force collectively produced by the rest.

Wang trespasses the old and the new, East and West, with a playful deviance that refuses to conform to the perceptional norm. The audience experiences the reinterpreted Uyghur festive beats, the free jazz arrangement of Chinese classical royal court music from the Tang Dynasty, as well as the rendition of Qinqiang (a folk Chinese opera melody, popular in the Shanxi and Gansu region in Western China), there is bass trombone and saxophone, and percussion ,as opposed to the traditional instrument, Suona.

And then there is the Buddhism chanting sample, which Wang says was collected from Bai Ta Shan (White Pagoda mountain), her hometown, Lanzhou.

Working on Cocoon has been a catharsis process for Wang, as the motif speaks to her inner dilemma as an artist, her ambiguous identity in an increasingly global context, where locality can work as a double edged sword. It is a piece about “origin, gestation, strength and growth” which reflects her creative will to break through current confines.

In this 35-minute rendition, audiences are left in awe of Wang’s versatility, fluidity, and command. Untrammeled by the musical forms and cultural norms. Cocoon is a daring and audacious piece.

In Between Two – a tender love letter with poetic beats

In Between Two offers an amalgamated universe of poetry, singsong, raw stories, and archival sound bites, where rapper genius, Joelistics (Joel Ma), and ARIA nominated musician and producer, James Mangohig, intersect their Asian Australian in-between-ness with a fiery passion, unwavering in continuing their ancestors unfinished sentences and exuberant mixes.

One vertical image, and one horizontal, form a retro portrait of a gothic-like wedding photo, featuring a 17 year old bride, a rice field of tropical green, and a village from the Philippines. Two screens drape with fading love, lasting memory, and electric beats, threading the lives of two young Asian Australians together (warning: the performance contains heavy references to TB, buffalos, and racially upsetting phrases).

Mesmerised by the grandeur of humanity in their personal stories, which are dotted by betrayal, regrets, and soothing bass, audiences are strung by Mangohig’s unflinching honesty. The whole space intermittently soars into a rhythmical hype when Ma owns the stage, either with his signature rapping, or his interaction with Mangohig, exchanging their shocking personal encounters of racism in Australia.

The switch between Ma and Mangohig’s stories sometimes seem sudden, lacking a deliberate narrative transition, but maybe that’s the point – reflective of the experience of growing up Asian in Australia, anything but smooth.

The Dark Inn – The lingering horror after a confusing dream

The smoke of cigarettes and hot steam from the onsen bath silently puff upwards, intertwining into one stream of consciousness, making it difficult to tell whether it is heavy with memory or light like those intangible bubbles that will burst into disappearance at any second. The void is eerily filled by a menacing string, played by kokyu. It feels like an immobilising, lucid dream. Snowflakes falling outside the window are made obvious by the encircling dim light, and they fall, and keep falling. A hypnotising viewing experience.

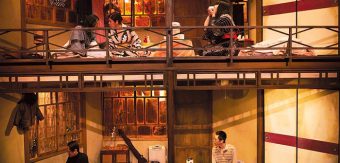

The story kicks off in the hot spa hotel in Northern Japan, unfolding in an orderly Japanese fashion, with repetitive greeting and bowing, before descending into a strange, hell-like space, with a piercing sharpness that examines isolation, preservation of tradition, sexuality, desire and even the Soul with a capital S. The Dark Inn builds a display room for human absurdity in different boxes with its sophisticated set design, spinning 360 degrees, where dark secrets are tolerated and reenacted. The onsen ritual, which consists of stripping, emerging in the water accompanied by extreme cold and hot sensation, rubbing with a towel by a sexually frustrated hotel attendee, is soothing and disturbing at the same time. It offers a temporary escape for the people in that world, but it also numbs their minds, like putting frogs in slowly-boiling water, overpowering all the characters with the greatest suppression.

The narrative is a classic, marked by a trajectory with a clear destination and objective. However, the slow pace of the play, its peeling layers of the onsen ritual, geisha performance and the characters unfulfilled wants, the puppeteer’s phallic act, continuously tormenting the storyline, interrogating the meaning, or perhaps meaningless, of it all.

The play is elusive, with depth and textures and a good dose of confusion that continues to lure the audience into the heart of the darkness. The dialogue is rid of any flourishes, with the fluidity that remains open to interpretation, may that be a core concept of Buddhism belief or a philosophical quest of self.

OzAsia Festival 2017, in Adelaide, pampered audiences and Arts enthusiasts with its almost trance like Asian-ness across theatre, music, and visual arts spheres, bringing with it an overwhelming energy generated from the depth and breadth of its programming, and after uncountable, mediocre flat whites, local Coopers Pale Ales, and a currently indisclosable number of cracking pork Baos and dumplings, I must conclude my OzAsia experience has been a satisfying one.