Agitators and organisers: untold histories of Chinese migrant workers in Australia

The stereotype of migrant workers is that of meek and compliant workers, exploited by their bosses as inexpensive labour. It was one that fuelled resentment against Chinese workers in Australia in the late 19th century. The history of the Chinese working in Australia was one of discrimination, from riots in Lambing Flats and exclusionary legislation passed by colonial governments, culminating in the White Australia Policy. Yet history shows that contrary to the cultivated image of compliance and exploitation the story of Chinese workers in Australia is far more complex.

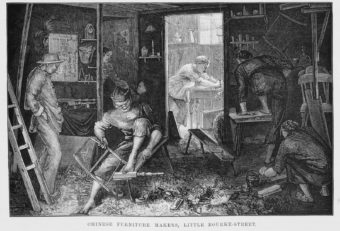

Chinese furniture workers in Australia understood the importance of collective action in the workplace, but they were not welcomed into the existing furniture trade unions. The unions saw them as unfair competitors and actively pursued an anti-Chinese agenda, claiming that Chinese workers undermined the pay and conditions of other workers. Working with other furniture factory owners, they formed anti-Chinese associations whose agitation resulted in discriminatory legislation and mandated the stamping of furniture as ‘Chinese labour’ or ‘European labour only’.

Instead, Chinese furniture workers in both Sydney and Melbourne formed their own trade unions, and took industrial action to fight for better wages and conditions. In Melbourne, a Chinese furniture workers union was formed in the 1880s and strongly fought for their members, waging major strikes between 1885 and 1903, winning better wages and conditions for their members. In September 1885, about 300 Chinese workers went on strike to fight for a weekly wage instead of being paid by piece work. By 1888, Chinese furniture workers in Melbourne had won the minimum wage, a fifty-hour work week, holidays and union preference.

While the 1890s depression affected the union, it became active again towards the end of the decade. In May 1897, between 400 and 500 Chinese workers in Melbourne took strike action after Chinese employers sought to dismiss workers who (in their view) did not warrant new pay rates under the amended Factories Act. Strike pay was organised by the union and the striking workers picketed workplaces to prevent non-union labour being used.

The strength of the union was such that in September 1903, several hundred took co-ordinated industrial action in Melbourne for better pay and conditions, walking out of factories simultaneously. Employers retaliated by locking out workers in October and bringing in non-union labour from Sydney. The tensions between strikers and these non-union workers led to clashes in November 1903 at the intersection of Russell and Little Londsale St and other sporadic incidents. The strike lasted for nearly three months, shutting down much of the industry until employers finally accepted union demands for a pay rise and for non-union workers to join the union.

In Sydney, Chinese workers formed their own union in 1890. The “Sai-ga-Hong” (西家行), the 400-member-strong union, called a strike in 1908 after factory owners attempted to charge workers more for accommodation and food. The strike involved nearly half of the Chinese furniture workers in Sydney. Workers held out for two months, eventually winning the right to elect their own foremen.

The Chinese furniture workers also sought to support and join with the wider trade union movement in Australia. During the 1890 maritime strike, one of the largest ever strikes in Australian history, they organised a donation for the strikers in Melbourne. Sadly, the solidarity they offered was unappreciated. In Melbourne, they expressed interest in becoming part of the Victorian Trades Hall in 1893 but their interest was ill-received. In Sydney, they also (unsuccessfully) tried to affiliate with the Trades and Labour Council in 1908. But despite of the lack of support and solidarity from the wider trade union movement, the militancy and gains Chinese workers made in Sydney and Melbourne displayed the strength of their collective action.

Chinese furniture workers unions of the late 19th century challenge the dominant story of migrant workers in Australia. One in which migrant workers lack consciousness and agency and need “saving” by benevolent people.

This forgotten aspect of labour history is not a phenomenon restricted to Australia. In Canada, Chinese workers formed their own unions and tried to affiliate with local trades and labour councils. In America, Chinese railroad workers were engaged in a huge strike as the transcontinental railway was being built, and Chinese garment workers in San Francisco engaged in industrial action. But these histories are not part of the official history of organised labour spoken about in America or Canada, and are largely ignored.

We more often hear about the exploitation of migrant workers in Australia. Precarity and other restrictions, such as reliance on a sponsoring employer, have weakened the bargaining power of migrant workers. But they are not all meek and compliant workers, unaware of wages and conditions. This is a flawed idea that continues to shape our discourse. Migrant workers have agency and they exercise it. From farm workers taking strike action to the long-running battle with Cochlear over bargaining, even today, Chinese workers continue the fight.

The story of those Chinese furniture workers and the ongoing labour struggles of migrant workers today challenge claims about language and culture being barriers, showing there is a universal understanding of power in the workplace through collective action. It should make us reassess these assumptions that shape the narratives about migrant workers that we are told.

Image citations:

“STAMPING OF FURNITURE ACT.” The West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 – 1954) 30 October 1900: 3. Web. 9 Aug 2019 <http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-

Chinese Furniture Makers, Little Bourke-Street. [Picture], 1880.

Very informative!