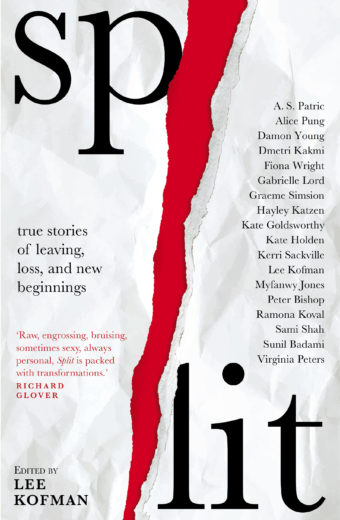

This essay by Sami Shah is extracted from Split – True Stories of Leaving, Loss and New Beginnings, edited by Lee Kofman (Ventura Press), available now.

Forget Me

I forgot. That’s where I made the mistake for which I’m paying. I forgot. I forgot how extreme religious extremists can be. I forgot how unforgiving nationalists can be. I forgot all of that. I forgot that Australia isn’t as far from the rest of the world as I hoped it was. And because I forgot, I screwed up.

I forgot. That’s where I made the mistake for which I’m paying. I forgot. I forgot how extreme religious extremists can be. I forgot how unforgiving nationalists can be. I forgot all of that. I forgot that Australia isn’t as far from the rest of the world as I hoped it was. And because I forgot, I screwed up.

See, I used to be a Muslim from Pakistan. That was my identity. We define our personal identity in many ways: we use gender, sexuality, ethnicity, racial constructs, religion, nationality. We pick and choose whatever aspects we want, but even more often others choose for us. In Pakistan, my identity had more fractal detail; I was a Mohajir, Karachiite, Shia, Burger (it is a long story). While these labels mean a great deal within a Pakistani context, they mean little outside. When I moved to Australia in 2012, my identity lost its socio-economic and ethnic nuances, becoming all about religion and nationality. I was a Pakistani Muslim. It is how

I have been introduced at comedy shows, on television and at writers’ festivals. ‘Ladies and gentlemen, Sami Shah is a Pakistani Muslim …’, followed by job qualifications, maybe. And it started to grate.

The Pakistani part is true and accurate. It doesn’t offend, because I will always be a Pakistani to myself, too. I’m learn- ing to be an Australian now, but I can never unlearn how to be a Pakistani. The ‘Muslim’, though, is less pleasing. I was born a Muslim in a Muslim country, and for most of my childhood and at least part of my adult life I identified as a Muslim. Then in my early twenties, I stopped. People do that sometimes. They grow up, look at the beliefs they’ve been consuming for so long, and realise these beliefs are no longer palatable. Religion, any religion, no longer appeased me. There was no single particular cause for the break, nothing that proved the dramatic equivalent of an old Spider-Man comic cover, with the costume in a bin as Peter Parker walks away, vowing to be the superhero no more. It was just a gradual awakening to my critical reading abilities, and then applying those skills to the precariously balanced architecture of organised religion and finding it is composed, not of bricks and mortar, but of cognitive disso- nance and hypocrisy. And so I stopped being a Muslim. Unfortunately, I then found out, this is not something that is allowed.

Islam is entirely capable of being a modern, progressive system that can coexist with democracy and even feminism, as long as you don’t read any of its sacred texts or follow any of its commandments. If you do pay it heed, it is exactly as oppressive, restrictive and regressive as all the other major religions. Muslims, Jews and Christians are at their best when they ignore almost everything their religions tell them to believe. I am sure the same holds true for Hindus, Buddhists and Scientologists too. The punishment in Islam for leaving Islam, for example, is not modern or progressive, it is death. The crime is known as apostasy.

The way most Muslims – in Muslim countries, where apostasy is a crime, and in Muslim communities abroad, where it can lead to social expulsion – deal with the apos- tates in their midst is by pretending they don’t exist, and the apostates show their gratitude at being ignored by pretending they are not what they are. Just don’t make a big deal about it and everyone will be fine. Which is what I forgot.

I think, in retrospect, it was the comfort I found in my new Australian life that lulled me into that false sense of security. Australia is a place where you can be who you want to be, mostly. There are still some limitations, but they don’t involve the same level of threat. You can be gay, trans, atheist, Muslim, black, and while each of these identities carries a certain stigma, the consequences are not codified into law, and usually are not fatal. Here, I can wear my apos- tasy proudly. And that is more freeing than people in the West can imagine. After suppressing and hiding my love of rational thought for a decade, while I pretended to believe in something I find unbelievable, being able to say ‘I am not a Muslim’ was intoxicating to me. So intoxicating that recently I wrote an entire book about it.

But even before writing it, I had already talked about my proud atheism on stage, in comedy clubs. It was invigorating to be able to express my true identity, and I did it often and loudly. The complete lack of reprisal emboldened me. So I did a radio documentary series about it. The series was not just about my apostasy, but also delved into the complexities of Australia’s Muslim community, one which is capable of being oppressive, but often is also oppressed. The entire exercise was my attempt at navigating the Australian Muslim world in a way that felt honest to me. I wanted to critique the religion and its believers without empowering the racists and far-right demagogues. I also wanted to show the Muslim community in all its colours and beliefs, which are more varied than simplistic media narratives would have you believe, and more sympathetic. The point I was trying to get across was that while we can criticise the religion, we should be more accepting of the believers themselves. This view is at odds with what Muslims themselves often demand – which is that while we can criticise certain believers, we have to accept the religion exactly as it comes. And then once the radio series was broadcast, heard by thousands of people, and no negative responses came my way, I wrote a book based on the documentary.

I know, I know. Why didn’t I just shut the fuck up and keep my lack of belief to myself? Well, I’m a stand-up comedian.

Which means I spend most evenings on stage with a microphone expressing thoughts normal people are too ashamed to articulate. There must be something broken inside my brain. Being the kind of person who has an idea then thinks that the world needs to hear this idea is clearly an illness for which I should have been medicated. But no one turned up at my door with a bottle of antipsychotic drugs. So I wrote the damned book.

To promote the book, my publisher put an excerpt in a national newspaper. Which is fine, because no one reads excerpts and no one reads newspapers. Until then, I had no concerns about what I had done. The book was in all the shops. I got to go on television to promote it, and I even did a joke about how much I enjoyed bacon now.

The first inkling of having made a monumental mistake came when I posted the video of that television appearance on my social media page. A few people laughed at my bacon joke. Then a relative disowned me. Right there, in a very modern way, in the comments section, an aunt in Pakistan posted a message demanding I change my name because I was bringing shame to the family, Islam and Pakistan. The severity of the response took me aback, but I considered her an outlier and ignored the comment.

The next day, the Daily Mail wrote an article.

The article in the Australian national paper would only ever be read by Australians. Even the TV show would only be seen locally, except on the odd social media post. But the Daily Mail goes everywhere. It is a tabloid with a reach that the New York Times envies. Its online posts travel across the social media networks like HPV at an orgy. And it turns out Muslims believe in three things. They believe in the Quran, which is the word of Allah; they believe in the Hadith, which are the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad; and they believe in the Daily Mail. Its headline, which I will not even quote because I’ve made a personal vow to never give that cancerous rag any legitimacy, made me sound like I was attacking Islam with all the virulence of a commercial radio host in Sydney, and a follow-up piece claimed I hated Pakistan more than an Indian cricket fan. The two articles combined to garner hundreds of thousands of comments and shares. A lot of those in Pakistan.

At the time when I became the target of Islamic extremists I was in Sydney at a geek culture convention. I had been invited to promote my recently published fantasy novel and had just finished a panel discussion, when a journalist friend from Pakistan called to tell me he’d heard the Taliban and its more modern iteration, ISIS, were after me. As he spoke, I watched my Facebook and Twitter feeds fill with death threats. Pakistanis around the world, Muslims around the world, all declaring me legally killable, and voicing their intent to follow their law, often by describing in graphic detail how they planned to do so.

I distinctly remember that while I was on the phone with my friend, who was describing the threats to my life, Chris Hemsworth walked into the room. He was there to promote his new Thor movie, and he was wearing a linen shirt that somehow managed to cling to each individual abdominal muscle. He sat down next to me, taking a break from the autograph line that stretched across the continent, and nodded a greeting. This, by the way, is no normal occurrence in my life. I do not associate with movie stars with biceps larger than my head on any basis. By then, so confused was I by the radical turn my life had just taken, I actually thought to myself, ISIS can’t kill me. Thor is here. For the first time in years I’d put my faith in a higher power; it just happened to be the Norse God of Thunder.

I returned home to Melbourne the next day. In that time, my family in Pakistan had already been contacted by every- one they’d ever known to inform them I was not welcome at any of their homes should I dare to return to Pakistan, and indeed I probably should not return to Pakistan. For the grief and fear I have caused my parents, I can never appropriately apologise. Driven by my need to be identified on my own terms, I have changed their identities too, in a place where such changes endanger you. They are now the parents of an apostate, with all the risk and shame this brings.

‘Why did you do this? You know how dangerous it can be,’ my father asked, repeatedly.

I still have no worthwhile answer. I did know how dangerous it can be, and then I forgot.

In the ensuing days, my anxiety began to flare. When every- one tells you ISIS wants to kill you, you start to believe ISIS wants to kill you. It is literally what the Australian government does whenever their poll numbers are flagging, and they wouldn’t rely on the technique if it wasn’t so successful. I spiralled. One night, I sat on a chair, peering through blinds, watching the cars driving past my house, wondering which one would be the ISIS car. I did this all night. At one point, a car came up my lane, stopping at every single house. I knew that must be it. Eventually it drove past my house, no doubt having identified it as the one to target.

The next morning, I went outside to find my car had a flat tyre. ISIS did that, I thought. Then, in a moment of clarity, I realised if ISIS’s modus operandi was puncturing car tyres, we would not be hearing of them so much; they’d have less success taking over large swathes of territory in Iraq and Syria.

I had booked in some comedy gigs before all this began, and I decided it would be good to keep those bookings, to find some comfort on the stage. It is where I usually feel at my most relaxed, with a microphone berating a half-drunk audience. I walked down to a pub in Melbourne’s CBD and as I approached the venue, a taxi pulled up and a man got out. To accurately describe him would require stereotyping, the kind of stereotyping we all abhor, and no one should have to experience. But, damn it, if anyone is allowed, it was me in that moment. He looked like a terrorist. He had the wiry beard, the Islamic cap, an oversized jacket. He looked so much like a terrorist he could have been accused of cosplaying as one. He looked straight at me. I pretended I hadn’t noticed him, and crossed the road, going into a bookshop and ducking behind a shelf. From there I peeked through the window only to see him walk away into the night. I did that show anyway, and as I stood on stage I saw three Pakistani men in the back of the room. I remember winding the micro- phone cord around my fist as I launched into a new stand-up routine, ready to use the mic as a weapon if attacked. But no one attacked. One of them came up to me after the show and said he and his friends were huge fans and tried to come to all my gigs. I’ve seen them at many of my shows since.

ISIS hasn’t, as far as I know, ever tried to kill me. The death threats were just that, threats. There were a lot of them, thousands per day at one point, but eventually, after a couple of months, they began to reduce to a trickle. In the interim I shut down my website and Facebook pages, limiting points of contact with strangers on the internet. I gave up on promot- ing the book entirely, letting it disappear from bookshelves as quickly as it could.

All of this hurt more than I thought it would. Being on social media, particularly Facebook, had been something I enjoyed. Many people who liked my work visited my page, and we’d usually engage in civil debates over everything, from international political developments to the correct way of preparing a carbonara. To see that page and its inbox get so inundated with abuse and hate that I finally had to cauterise it was not an easy choice, but it felt necessary.

The same goes for all the promotional work for my book, as well as some major public appearances I decided to withdraw from. I felt safe popping into a comedy club, where the only people in attendance tend to be drunks and other comedians. But writers’ festivals, author talks, even recording a one-hour comedy special for ABC in front of a live audience, all of these felt too unsafe. Opting out of all these engagements, and at short notice, was more than just a financially difficult choice. (I lost almost half of my annual earnings, and had to struggle to make basic rent for the next few months.) It also felt like setting back a career I’d nurtured carefully over the last decade. However, it made sense in terms of both physical safety and psychological wellbeing. All of which is deeply ironic when you read all the comments angry Muslims make online about how the only reason anyone becomes an ex-Muslim is so they can gain fame.

In the days when all this was happening to me, a young man in Pakistan, Mashal Khan, might have posted some content that hinted at his atheistic leanings on his Facebook page. This is all uncertain still because while there’s been no evidence of his having posted such content, his killers claim he did, and his murder is considered largely justified for that reason. Khan was beaten to death by an enraged mob on his university campus. Footage of his violent death circulated on Pakistani social media spaces, and came unbidden onto my Facebook wall.

I became obsessed with reading about Khan and watch- ing the footage, as this was the reality of what I’d just risked happening not just to me but to family members in Pakistan who might be targeted in association. The story triggered severe traumatic reactions that finally sent me to a psychologist, for the first time in my life. Even now, whenever one more person is killed in a Muslim country for daring to question the religion, all while many Muslims claim theirs is the most peaceful religion, I am filled with rage. Rage that I then push away because of how utterly impotent and futile it is. The very tolerance I advocated towards Muslim communities in my book was what I was now having trouble justifying in my life.

From then on, I’ve made every effort to avoid talking about religion in any public forum. If people want to call me a Muslim I let them. If they want to call me a ‘murtid’ (someone who stops being a Muslim and thus becomes the focus of God and his believers’ wrath), I let them.

Surrendering my Muslim identity was something I chose to do. Doing so as loudly as I did was a poor choice, given all the risk it placed on my loved ones. But it was still my choice. The Daily Mail articles, however, made the claim that I was happy to no longer live in Pakistan and thus implied a surrendering of my Pakistani nationality and identity. It was taken literally by Pakistanis everywhere, who now consider me a traitor and often take the time to call me so online. That wasn’t my choice at all.

I can’t go back to visit Pakistan. Not now, maybe not ever. I have family there, friends there. Even though the Daily Mail has given up using me for clicks now, as they can only run the same old story so many times, it began a trend that Pakistani newspapers and blogs are continuing.

Every time I think I might be forgotten, a new website or YouTube channel decides to use my notoriety to promote itself. Pakistanis and diasporic Pakistanis, who tie religion closely to their national identity, began adding their own fictions to the original message, like a game of Telephone but with real-life consequences. I wasn’t a Pakistani immigrant who came to Australia on a work visa several years ago, I was now a traitor who gained Australian citizenship by maligning Islam and Pakistan. The belief being that there is some fast- track path to citizenship available if you simply walk into an Australian embassy and say, ‘I hate Islam and Pakistan.’ To this day, several thousand abusive messages enter my life every few months, mostly through email and sometimes slipping past the strict filters I have on my Twitter account, and I’m reminded regularly that should I ever return to my birthplace, I risk recognition. And with recognition comes death.

I miss being Pakistani. There is a restaurant on the side of the road in Karachi, where you sit on rickety chairs on a footpath and eat crabmeat biryani so spicy your hair bleeds. Every time I went back, my friends and I would go there and talk politics and comic books late into the night, the tower of empty plates tottering in front of us. I can’t go back there again. The only chance I have now to fulfil my longing is if I am forgotten. Just as I forgot the dangers of being who I am, I now hope, with time, I will be forgotten for being who I am.