Dragon Ladies Don’t Weep

Margaret Leng Tan’s sonic memoir is joyful and intriguing.

The night opens with a support act of sorts: Double Phase, a collaboration between Japanese filmmaker Makino Takashi and Australian composer Lawrence English. It’s a 25-minute audio-visual acid trip through abstract imagery and dizzying soundscapes that ooze and lurch between the organic and the industrial. Beginning with a low drone that rises in pitch like a plane lifting, the music evokes wind whirling through caves, crashing waves, and a prehistoric, elemental hum as the screen shifts from the tulip palette of 1980s cosmetics to the gritty greys and greens of military archives. Though abstract, the footage – shot on location in Australia – suggests a scarred and haunted country, while the plaintive and relentless soundtrack reverberates through your teeth.

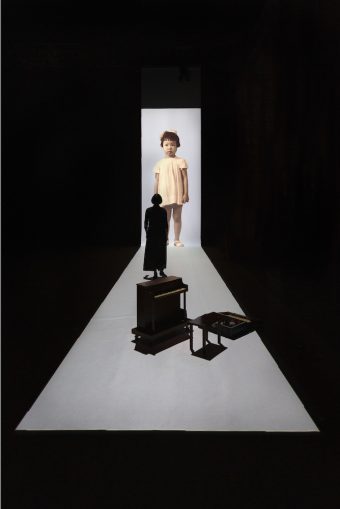

After a palate-cleansing interval, we re-enter and re-centre ourselves in preparation for the main act: experimental pianist and toy instrumentalist Margaret Leng Tan. The stage is set with a glossy black grand piano and a doorway framed in white light. Tan begins by counting aloud while playing an insistent melody. She rises to push the piano in a tight circle, continuing to count as the climbing numbers suggest childhood games that toy with fear and tension. There is a sense of foreboding in these carefully enunciated numbers, until Tan stops at 74 – her current age.

An icon in the world of avant-garde music, Tan has a charming and formidable presence as she sweeps across the stage playing various instruments – toy piano, prepared piano, a brightly coloured melodica, music boxes, a plastic toy cashier, and so on – while sharing her thoughts and memories. In the program, Tan says that Dragon Ladies Don’t Weep is her ‘first fully-fledged foray into theatre’ but her more than half a century of performing experience is clear from the beginning: she’s put together a great team of artists and every aspect of this production is polished to a high gleam.

Dragon Ladies is a memoir of sorts, combining music, storytelling and stunning projections to offer a meditation on ‘memory, time, control, and loss’, and also a homage to two major figures in Tan’s life: her mentor, John Cage, whom she first met in 1981, and her mother, who passed away in 2018 at the age of 98 with her final years clouded by dementia. That undercurrent of playful anxiety that you feel in games like hide-and-seek buzzes beneath this performance, bolstered by a few Cantonese nursery rhymes from Tan’s girlhood in Singapore. The narrative, the music – by Tan’s long-term collaborator, composer Eric Griswold – and the visualisations all dance with the tension between precision and improvisation, between playfulness and perfectionism.

Tan has lived with obsessive compulsive disorder for as long as she can remember. At the age of six, she demanded piano lessons, which helped channel her obsessive impulses into a creative outlet – ‘this is where the counting belongs’, she says. At 16, she left Singapore to study at Juilliard, where she built a career first as a classical pianist until she met Cage, who transformed both her approach to music and to life. Influenced by his take on Zen philosophy, Tan writes that she has ‘learned to relinquish the grand illusion of the goal and relish, instead, the unfolding of the process’.

Watching the process unfold here is a delight. For the prepared piano, Tan manipulates the strings with bolts and other hardware to produce surprising music while, on the back wall, striking black and white projections echo the notes as graphic lines cross and collide. In some parts, the music is looped, with dense layers of melody folding in on themselves. In others, each note is like a droplet falling from an icicle of pure sound. At one point, the recorded sound of a dog eating biscuits gives me ASMR tingles. Early on in the performance, scrolling text subtitles Tan’s English monologue in Chinese, and then her Cantonese speech in English, the spoken and written languages slide and overlap like piano notes. Another moment that leaves an indelible memory is Tan pouring rice over cymbals – each grain striking and glinting off the surface, then cascading into the dark.

The show is also a portrait of Tan herself, who is quite a character. She’s ballsy, witty, and exacting, with a penchant for aphorisms and a wealth of influences and references running through her quick mind as she quotes people ranging from actress Regina King to playwright Samuel Beckett. With the particular inflections of an English-speaking, western-educated woman with roots in southern China, a hometown in southeast Asia, a home in New York, and a unique, extraordinary life, Tan also embodies and deconstructs the familiar archetype of the dragon lady. Her version of the dragon lady is a decisive, demanding perfectionist, yes, but also a goofball, an aesthete, a daughter mourning, a septuagenarian anxious about the future of her mind and the planet, and a performer who will capture your attention completely. You imagine that if you had the privilege of collaborating with her, she’d gently mock you while also extracting from you the best work you’d ever done. You leave convinced that there’s nothing dragon ladies can’t do.

Dragon Ladies Don’t Weep

A co-production by Chamber Made and CultureLink Singapore

Musician/performer – Margaret Leng Tan

Composer – Erik Griswold

Director – Tamara Saulwick

Dramaturg – Kok Heng Leun

Video artist – Nick Roux

Lighting designer – Andy Lim

Costume designer – Yuan Zhiying

Presented at Arts Centre Melbourne as part of Asia TOPA

28 February 2020: https://www.artscentremelbourne.com.au/event-archive/2020/asiatopa/dragon-ladies-dont-weep

Sydney Opera House will present Dragon Ladies Don’t Weep 18-20 March 2020: https://www.sydneyoperahouse.com/events/whats-on/unwrapped/2020/dragon-ladies-dont-weep.html