There is little that is extensively known about the communist movement in Malaya, at least in the mainstream.[i] There are pithy records of course, about how the surge of communism in both China and Indonesia sowed the seeds for the formation of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP). The economic crisis that occurred around the onset of World War II accelerated the establishment of leftist committees and labour unions, made up of members disappointed by the reality of British colonial rule. Four years under Japanese occupation further stoked communist sentiment, but when Malaya split to become present-day Malaysia and Singapore in the 1960s, many of these operations again went underground, especially as each newly formed national government sought to eradicate activities that ostensibly served to undermine democracy.

Power takes power-seeking turns: it must be noted that many who had seceded from communist affiliations went on to form their own authoritarian governments. Through a series of negotiations, incarcerations and coups post-independence, much of communist history was suppressed in Malaysia and Singapore, its stalwarts either having been imprisoned without trial, in exile overseas, or dead. Communism’s epoch remains a footnote in Malaysia and Singapore’s history, if it was believed to have existed at all. Too much has been decimated.

The figure of Lai Teck follows this path. A leader of the MCP from 1939 to 1947, he was active during a time of heightened uncertainty, when both the British and Japanese regimes fought to lay claim to parts of Southeast Asia[ii] while World War II raged on in full force. But Lai Teck also worked as a triple agent for the French, British and Japanese secret police, engaging in numerous morally ambiguous acts to result in his rise to the top. After his acts of treachery gradually became uncovered, he disappeared. He is thought to have used more than thirty pseudonyms throughout his lifetime, which has made his history and movements difficult to determine and trace.

**

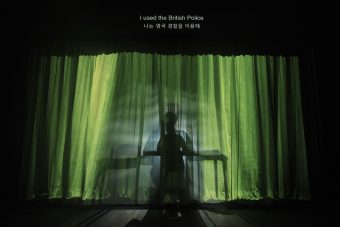

Acclaimed Singaporean artist Ho Tzu Nyen’s new work, The Mysterious Lai Teck, is built around this figure. As the title suggests, little is known about Lai Teck across the annals of history. When the show begins, the curtains remain closed; it is through the veil of projection that the audience hears Lai Teck’s story, a monologue in Mandarin Chinese accompanied by English subtitles projected above the stage. The shadow of a figure looms ominously, an air of suspense permeating the room as the languid voice (Tay Kong Hui) drawls on. We hear about Lai Teck’s journey from Vietnam to Malaya, and the numerous roadblocks he encounters, the tricks he pulls along the way. “I am the shadow of Ho Chi Minh,” the voice intones over and over.

But Lai Teck’s voice simultaneously reveals untruths. Ho is known for blurring the line between fact and fiction in his explorations of Southeast Asia’s cultural histories, and The Mysterious Lai Teck does not stray from this path. As Lai Teck’s ‘account’ continues, contradictions present themselves. He had not come from the same town as Ho Chi Minh after all. There’s a possibility that he was not sent by the French to Malaya. The act of the curtains opening is repeatedly simulated through the projection while the actual curtains remain closed. However, if not for Jeffrey Yue’s evocative soundscapes that crescendo with each untruth, and Andy Lim’s complementary lighting, the experience would be akin to listening to a podcast.

The curtains finally fall away in the second act. Seated on the stage at a makeshift desk is an animatronic figure hunched over in a writing stance, with a video of the voice actor projected on him, which creates an eerie, uncanny valley effect. This is meant to be Lai Teck himself, and he continues to delve into his exploits throughout the years. As he travels through the former Indochina and the Malay Peninsula finally to arrive in Singapore, his trail of espionage follows him. We hear about his co-option by the French, his eventual infiltration of the MCP as a spy for the British, and finally his time as a Japanese double agent that allows him to walk free after Singapore falls to the Japanese.

To Lai Teck, the only constant is himself—this certainty gives him licence to continue grifting until he arrives at satisfying conclusions, even if they inevitably become a means of escaping his own delusions. The torrent of lies builds, but they simultaneously collapse into each other, clouding his own sense of identity. At one point, the voice speaks of “ghosts and gaps”, a nod to the combination of historical and oral history that Ho managed to collect for the making of the show. Indeed, how do we separate truth and lies from history? The Mysterious Lai Teck ends with a laboured count of the I Ching, the voice outlining the symbolism behind each number until it abruptly stops at the forty-ninth hexagram. Like Lai Teck’s life, there are both opportunities and dead-ends; clean slates are arrived at over and over.

**

I didn’t learn about Malaya’s communist history until I became fervently involved in Singapore’s underground punk and metal scenes as a young adult. Being a small city-state, alternative characters would often cross-pollinate: it wasn’t uncommon to see musicians, artists and activists congregating in the same room, discussing similar ideas, plotting the same events. In Singapore, being involved in non-mainstream pursuits is often considered revolutionary in itself. Above ground, freedom of expression is stifled, and suppression of information par for the course. It was through these networks that I—working-class loner, school drop-out, completely adrift—even learnt about anything at all.

Through activist elders, friends and book recommendations, Singapore and Malaysia’s true history slowly unfolded. I mostly learned things I hadn’t heard about in school, even if I had been paying attention: about Operation Spectrum, the alleged Marxist conspiracy that sought to arrest leftists and imprison them without trial in the late 1980s, and Operation Coldstore before that, both having left discomforting marks across civil society—a residual feeling of apprehension when it comes to speaking out against the government. I read accounts from books like Beyond The Blue Gate and Dialogues with Chin Peng. Undoubtedly, there are still gaps, much left to be uncovered beyond what’s already been collected; an archive of loss that relies on fervent digging and a collective hope to survive the total annihilation of information by repressive regimes.

This is what I think of when it comes to accessing cultural identity. Instead of conveniently leaning on the conservative ethno-nationalism that permeates much of diasporic discourse, how do I claim allegiance to a culture that persistently sends me the message that my political beliefs—and thus, my sense of self—are flawed? I am sick of looking to the so-called ‘more liberal’ western world for advice, its own agenda to conceal its crimes, which are much more insidious. Perhaps it is through “ghosts and gaps” that I can coalesce a modicum of self-understanding, a rejection of parochial histories in order to access a more globally interconnected decoloniality, a diasporic left that aspires to not only recognise the distorted nature of colonial projects both in the west and elsewhere, but to find solidarity through its desire to hold space for alternative cultural histories.

**

Perhaps it is only the muddying of fact and fiction that can undercut this already-obscured history. The aims of The Mysterious Lai Teck may appear on the surface to be a cursory history lesson, an aestheticisation of communist revolt that through its deliberately vague retelling serves to both fuel the uncertainty of Malayan history and skirt around national censors. But like the voice of Lai Teck reminds us, we are made of two bodies—that “of blood and of words”. Paired alongside Ho’s past (and ongoing) work The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia, which makes use of algorithms to weave together different sets of sounds and images to form an abecedary of Southeast Asia The Mysterious Lai Teck affirms the idea that many possible pasts can exist—a collage that doesn’t hinge on the dubious responsibility of ‘truth-telling’ to build alternative futures.

[i] Malaya comprised present-day Malaysia and Singapore.

[ii] A colonial term used by the US military in 1943 to coordinate Allied forces in the region.