“If only recovering the silenced history / is as simple as smashing its container: book, / bowl, celadon spoon. Such objects cross / borders the way our bodies never could.”

—Sally Wen Mao, “Occidentalism”

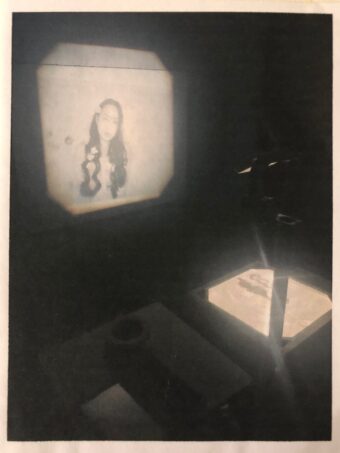

There’s a memory that persists, despite all these years, in which I am staring at a photograph of myself projected onto a white wall. In this impression, I am seventeen, standing in the makeshift library of the art classroom where I spent most of my final year of high school. I am tracing this photograph, a self-portrait, onto a large sheet of watercolour paper—another self-portrait. When I raise my hand, I mirror the outline of my body in the projector’s beam. Alone, emboldened, I press my cheek against her cheek, which is my cheek, and yet also not. The wall is cold against my skin. I recoil like I’ve been stung. This act feels perverse, and maybe it is. I am startled by the distance between my body, the bridge that is my shadow, and the self in this photograph that emits light, or perhaps, is borne out of it.

I call this an impression, in the way that some memories exist only as brief images, flickering out of dimly lit rooms. Impressions are not ignited by familiar pangs of the heart, like hearing a stranger call the name of someone you love; rather, they simmer. They are almost forgotten, dream-like, soft at the edges. They require some distance. I still have the pieces of my Visual Arts major work sitting in the garage, but it is this moment that I return to, that has been so gently impressed upon me: that very first discomfort of watching myself watch myself—subject, object, girl.

Later, when my Visual Arts teacher says you photograph beautifully, I understand what she means: I am not beautiful, but perhaps I could be, under a certain light, through a camera lens.

I begin to think of myself as a measure of surfaces—where my body goes without me in it. I am both fascinated and nauseous, and sometimes the feelings blur into one, low and heavy in the pit of my stomach. I will attribute this alienation to my Unsolvable Teenage Angst, or what Jenny Zhang calls “the kind of intensity that is only acceptable between the ages of thirteen and nineteen”.[i] I will wonder why I still carry that intensity, in all its magnitude, beyond girlhood, beyond the boundaries of flesh, in both life and art. I will grow older, and think of this grief in me as ancient, of Louise Glück saying: “I didn’t even know I felt grief until that word came.”[ii]

*

Anne Anlin Cheng’s 1997 essay “The Melancholy of Race” opens with a single question: “Is there any getting over race?”[iii]

I ask this of myself often. At the dining table, where I write; in my English class at university; at work, while shelving books in a grey city, feeling strange and unsociable. Some white guy says ni hao and I say hi how are you and another says you know I love the Philippines and I say do you need help with anything?

As Cheng posits, the process of racialisation is a melancholic act itself. I do not appear until I am named, and when I am named, I am not only the Other to the external world, but also to myself. To be what Cheng refers to as a “yellow woman” is to be defined by artifice and aesthetics, eternally caught between thingness and personhood. Her theory of Ornamentalism identifies a particular type of haunting where Asiatic femininity is also untethered from the gendered, racialised body of the Asian woman:

“Culturally encrusted and ontologically implicated by representations, the yellow woman is persistently sexualized yet barred from sexuality, simultaneously made and unmade by the aesthetic project. She denotes a person but connotes a style, a naming that promises but supplants skin and flesh”.[iv]

The yellow woman is not a real woman in the same way that I am, but her existence continues to haunt my own corporeality: in the mirror, in paintings, on the screen, in the delicate shards of Chinese porcelain and silk robes, suddenly a conduit. She is not my product, but my precedent. She watches me, and I watch her back. Neither of us speak; I almost think it could be poetic.

*

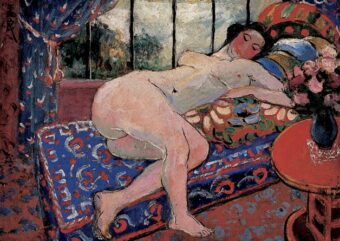

In Pan Yuliang’s The Woman Before the Window (1940), a naked woman is caught between two scenes: the interior space of the bedroom she is lounging in, and the misty landscape outside her window. Against the rich Fauvist colour palette of her surroundings, her skin is a pale peach pink, softened by shadows of Russian green and lavender. As she gazes away, she offers her body for the viewers’ pleasure, along with the luxurious patterned fabrics of her bedsheets, her curtains, the vase of flowers beside her. This painting is lush, sensuous, and deeply familiar. Rehearsing Orientalist iconography, it evokes a sense of opulence and desire that has been sustained through Western myths of the exotic East.

While the body is undeniably a significant part of Pan’s practice, its value lies in more than just its physicality. Like many diasporic artists, Pan’s self-portraits are not merely reflections of her identity, but a process of identification—she produces and constructs Asiatic femininity as it is entangled within her own ‘othered’ subjectivity. The very medium of oil paint itself is a call to sensuality; a continuous act of self-fashioning through the shaping of flesh. This constantly shifting identity is present in Pan’s nude portraits as she places her own body within the boundaries of subject and object. The Woman Before the Window is clearly complicated by Pan’s role as both the owner of the work, and the desired object of the Oriental fantasy. Art historian Phyllis Teo comes to the same ambivalent conclusions: “While she is the maker of the work, Pan sometimes appears to be the participant and perhaps the voyeur of her pictures as well.”[v]

Reading this, I can’t help but hear Margaret Atwood chanting in my ear like a scratched record stuck in a loop: Male fantasies, male fantasies. You are a woman with a man inside watching a woman. You are your own voyeur.

I have mulled over this quote for years. As a teenager, it brought me comfort in the way that all books did, giving shape to feelings I couldn’t name. What was once illumination and gratitude has quietly morphed into unease. Perhaps melancholy is the only word that can suffice, entangled so deeply with Cheng’s race theory in my mind; a heavy word, like grief, like angst. Can words carve out space for the visceral? Sometimes I think it is an act of love to hold myself at arms-length, the only way I know how.

*

At a Nicer Tuesdays live event, contemporary artist Yushi Li describes herself as “a Chinese woman who takes photographs of naked Western men in the UK” and the audience bursts into scattered laughter.[vi]

I watch this talk a year after it has occurred, through the small window of my laptop screen. Like many others, I am mystified by Li’s artworks. Her series of photographs are visually striking, but even more profoundly absurd and uncanny.

In Your Reservation Is Confirmed, Li poses with various white men in an ‘ideal’ home’ she has booked on Airbnb. There are layers to her process, as she uses analogue film to photograph people she has met through modern technology, which are then uploaded onto the Internet; miniaturised and pixelated.

Like Pan’s The Woman Before the Window, Li’s photograph Play-Doh (2018) is a bedroom scene brightened by the light of a window, with a nude figure half-sprawled across a mattress. The eroticised naked body is not the Asian woman, but the white man beside her. Li sits fully-dressed and cross-legged on the bed, staring straight at the viewer. She tightly grasps the camera timer, whose visibility in the shot is a purposeful disruption of the barrier between the audience and the constructed image. Li seems to be in a position of power, figuratively and literally controlling the shot. However, in this set-up of staged intimacy, that power is constantly shifting between Li, the man, and the audience who is watching. We are confronted by her small frame and youthful face, and the startling experience of seeing an image that disturbs the expectations embedded in a history of visual culture. We are also aware of our own participation in this scene as intruders and observers—who is truly in control?

While Play-Doh involves a bedroom and a naked body, it is not an intimate scene—it is idealised, unreal, and uncomfortably alienating. As Cheng notes, “having been made stranger to oneself by unimaginable brutality means that one must reapproach the self as a stranger”.[vii]

This is made explicit in Li’s comments on Your Reservation is Confirmed:

“For me, the woman in the picture is not really myself but a female figure who functions in the same way as the man, the table, and the teacup. In a way, we are all just props for the image I want to create. What attracts me the most is not really the body, but the fantasy of being in control.”[viii]

The fantasy of being in control automatically places the speaker in a position where they are not. For many Chinese women artists working in the West, self-representation is complicated by a history of estrangement and politicised embodiment. It is not necessarily a problem of objectification as much as it is a question of how personhood has become entangled with, and sometimes substituted for, the inhuman. Ornamentalism as the synthetic “yellow woman” that persists despite the absence of flesh leads to an alienation that disrupts the notion of subjectivity for a free and autonomous subject—an ideal that has long been considered a staple of Western feminist art practice.

As Flaudette Datuin explores in “Women Imaging Women: Feminine Spaces, Dissident Voices”, the body is a distinctive key term in feminist art, but not as a biological entity—as women re-image themselves, the body becomes fissured as a source of both oppression and liberation.[ix] In between the interplay of corporeality, thingness, and displacement, Cheng notes that in most racial and gendered discourses “we end up with a longing for that lost and violated flesh or, inversely, a total refusal of the body.”[x]

If any word is capable of enticing visceral feeling, it must be longing; drawn in the loop of its circles, and the vowels that string them together. I have written and read about the body and its desires in countless ways, and each time I feel less and less of myself. I am not sure what to make of this. Sometimes I’m scared that I am not allowed beauty because I care too much about what it means. I curl my fingers around the angular slope of my wrist until it almost hurts, and a line from a poem by Anne Carson lingers: “My personal poetry is a failure. / I do not want to be a person. / I want to be unbearable.”[xi]

*

This winter I feel a distinct desire for Asia’s heat—for a summer that is not just warm, but sweltering. My phone tells me I was in Shanghai on this day last year, so I flick through the photos compiled in the automated album Memories. I am greeted by pictures of open-armed wilderness, green spilling out from cracks in the sidewalk. I don’t have many photos from this trip, only passing moments: rows of pink flowers along the highway, raindrops on the hotel window, my parents in the garden. That year 爷爷 died, and we spent two days folding joss paper for the funeral. We spoke through our hands because we didn’t share language, and kept the incense burning all week. When I close my eyes, I can still remember the smoke in my grandparent’s apartment—not the scent, which filled the room entirely—but its visual quality; a slow, eternal, ungraspable shape, like our silver ghost money in flames, only carrying the remnants of touch in its careful creases.

I am thinking of this now because my phone says it is time to remember, even though I am not sure that I want to. Lately, I have been giving in to these quiet discomforts, the same way I used to indulge in small joys. I don’t hear about Shanghai in the news anymore, but my father’s WeChat messages still come through, infrequent and hopeful: the weather is hot here, we are ok, be healthy be happy.

*

It is difficult to write about art without also considering my place in this particular moment. I don’t feel safe going outside anymore, and I am beginning to feel a different type of estrangement from my body. When someone stares for too long, I am unsure if they might recognise me, or if they want to hurt me. In this slight pause of uncertainty, I wonder what has been inscribed on my body without my consent. If they are actually looking at me, or elsewhere; at the impression in the projector’s light, or the ‘yellow woman’ who exists in the incorporeal absence of flesh, but also in the flesh itself. What is at stake when the body is framed as a site of autonomy? What do I lose from misrecognising myself?

*

At night, I imagine what it would be like to be unbodied. In dreams and in life, I am always mourning something. I miss going to museums, and it feels selfish. I haven’t touched anyone for a long time, but I’ve been looking at pictures, trying to see what lies underneath.

[i] Jenny Zhang, “How It Feels,” Poetry Foundation, September 6, 2020, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/articles/70231/how-it-feels

[ii] Louise Glück, “Trillium,” The Wild Iris. (New York: Ecco Press, 1992).

[iii] Anne Anlin Cheng, “The Melancholy of Race,” The Kenyon Review, New Series, 19, no. 1 (1997), 49–61.

[iv] Anne Anlin Cheng, “Ornamentalism: Feminist Theory for the Yellow Woman,” Critical Inquiry 44, no. 3 (2018), 415.

[v] Phyllis Teo, “Modernism and Orientalism: The Ambiguous Nudes of Chinese Artist Pan Yualing,” New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, 12, no. 2 (2010), 78.

[vi] It’s Nice That, “Nicer Tuesdays: Yushi Li,” YouTube, accessed August 25, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B6c_M4cNARU

[vii] Cheng, “Ornamentalism,” 446.

[viii] It’s Nice That, “Nicer Tuesdays: Yushi Li.”

[ix] Flaudette May V. Datuin, “Women Imaging Women: Feminine Spaces, Dissident Voices,” in Text and Subtext: Contemporary art and Asian Women, ed. Binghui Huangfu (Singapore: Earl Lu Gallery, 2000), 19.

[x] Cheng, “Ornamentalism,” 436.

[xi] Anne Carson, “Stanzas, Sexes, Seduction,” The New Yorker (December 2001), 68.

Wow Donnalyn! It is almost haunting how you have talked about your relationship with the body as a product of fantasy and as something that is not always in your possession. The body operating as a surface is something I have been learning about recently so this was a very significant read for me.This is so special, thank you for writing this.