It takes time for the fatigued body to accept it needs to rest. Struggling through a period of disturbed sleep, I stumble on Ngram Viewer late at night, a Google tool that tracks word usage in published books from 1800 to 2019.

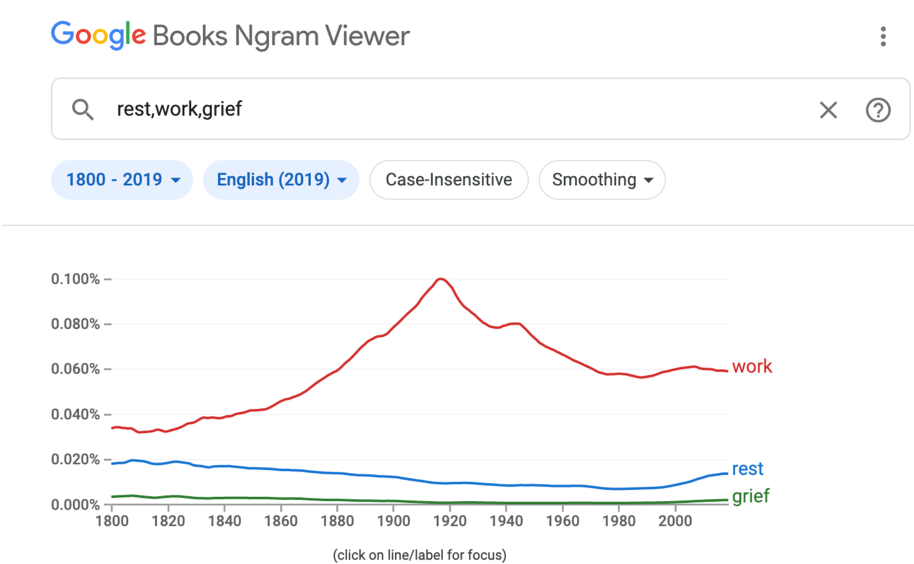

I type in: work, rest, grief. The results reveal that ‘work’ has dominated published books since 1917, and is being written about at the same levels for the last 50 years. Writings on ‘rest’ and ‘grief’ are much lower, but ‘rest’ is being published at an increasing rate for the last 40 years.

The gulf between ‘rest’ and ‘work’ is wide. ‘Grief’ appears almost absent, lying flat against the x-axis, breathing into the shallow, white space.

*

It is pre-pandemic, and I have already forgotten how to sleep. There is a sharpness behind my eyelids from the lack of sleep, a relief that only sets in when I close them, briefly. When schools close down in the first lockdown, I am relieved. I consider waking an hour late; using the commute time for sleep, creating space for resting.

The word ‘rest’ is rooted in the suspended activity of the body, an “intermission of labour; mental peace, state of quiet”. There are few acceptable resting periods in a school. Teaching work, like other work in neoliberal conditions, is preoccupied with efficiency, results, competition. The teachers and students I know are both tired and determined, their fatigue a problem to solve rather than a function of the body. As a teacher within this framework, I arrive at the pandemic already drained.

*

Moving my teaching practice to online learning means a flurry of preparation and apocalyptic planning overnight. There is no guarantee of when I will see my classes again; I sense a heightened state of panic setting in for students who, a day earlier, had stopped me in the corridor, sharing their enthusiasm for a storm outside that mirrored the pathetic fallacy in Macbeth’s Act 1, Scene 1: The Three Witches. Returning to school a few months later, I notice their economical use of limited energy during classroom discussions.

In ‘A Little History of Fatigue’, Tom Melick writes:

“Fatigue…comes and goes; it cannot be enclosed between a beginning and an end; it does not acquire value. It is a reduction, an instant, a slowing down.”

Teaching from home is to care beyond the boundaries of a physical place of work, encompassing both personal and professional time. The responsibility of care becomes ongoing and perpetual, the body languishing as overwhelm sets in, a fog of slowness descending the days. Where, once, the physical location of a school marked the beginning and end of a working day, now work and home become one, measured by fatigue that “drag[s] along the ground…express[ing] itself with a heavy sigh” (Melick). This mental fatigue accrues with each additional lockdown.

My expectations of working conditions, however, change. At first, walking from my bedroom to the desk doesn’t feel like I am working. I have access to coffee, regular toilet breaks, time to eat – none of the conditions I was used to as a teacher working in a classroom.

Except, many of my students become ghosts. Starting each online lesson with roll call, I see a black box light up with a blue border, a distant voice yelling ‘here!’ before disappearing for the next 45 minutes. Some don’t appear at all.

Fearing missing students, my days consist of sending emails to parents, the concern heightened, distorted, desperate, as the many lockdowns continued.

X did not attend English Period 5 and 6 today. Could you please get in touch and let me know if there is anything I can do to support

X has missed 3 classes in a row, and is struggling to keep on top of assigned work. Please speak to X and let me know what I can do to support.

We are nearing closer to the final English assignment for this term. In order to pass this unit, X must complete the attached adjusted tasks. I am happy to meet X outside class over the next three weeks to help X catch up.

Lying in bed, I make mental notes of who responds, and who I will call in the morning. Work becomes indivisible from the maintenance of home life:

Answer emails, empty bins, plan lessons, schedule student catchups, cook lunch, prep dinner, send a voice note home, pay rent, meet students online, schedule water bill, email parents, cook dinner, clean kitchen, shower, do laundry, eat dinner, write to do list, answer emails, empty bins, check news, answer emails, call home.

The only part of life that doesn’t feel like work are the WhatsApp messages I receive through the night from London, a mix of memes and a space to grieve the passing time in which nothing happens. My mother asks me to come home, so we can isolate together. She doesn’t know how to care for me across oceans.

*

In a capitalist-pandemic framework, the language of care assimilates into government jargon, evident in public health messaging persuading people to stay home and save lives.

Fatigue, however, is still wasted time under capitalism.

On waste, Chi Tran writes:

“We sit, we fold, and we bereave our own waste.”

If waste is unwanted materials, a byproduct of no value, then to bereave waste is paradoxical in a capitalist world; it produces nothing of value.

But to consider the possessive pronoun in “our own waste” changes everything – suddenly, waste has value capitalism cannot quantify: sentimental objects like a Nokia brick phone, enduring memories from a different era, or the state of time passing through our fatigued bodies. This type of waste exists outside the mode of production or quantification and has a value that capitalism cannot understand. Tran writes:

“I occupy space, which is to say, I am always grieving.”

I listen to my ongoing fatigued body as information. This information creates emotional permission: for slowness, sleep, and time to grieve what we lost, and are still losing. I will be grieving for however long we remain in this space.

*

Inside lockdowns, time elongates horizontally across the day, whilst my focus shrinks. For a while, poetry is the only thing I can digest. Re-reading Jack Underwood’s poem ‘An Envelope’, I scan over the extracts of lines:

What about the days when you feel nothing.

This is not sickness

This is not anything. Hand gripping

the big knife cutting onions. You could

cut fifty onions this way.

“This is not sickness / this is not anything” is the same suspension of time I feel in lockdown. Underwood writes not only of “cutting onions” but the ongoing-ness of cutting “fifty onions this way” that mirrors an autopilot fatigued state. I am distorting the lines, leaving out sections of his poem to understand things. There is nothing related to the pandemic in his collection, and yet, publishing the collection in 2021 creates an inescapable context resonating through the pages. This domestic-centered poetry helps me to focus on the smallness of life, the narrowness of daily tasks that facilitates a slower pace.

*

Slowing down leads me to look outwards; I am looking outside more often, counting the number of times in the day the seagulls and cranes swell in the sky.

To mark the beginning and ending of days, I make up rituals of light: turning the computer off, lighting candles and tealights, switching on fairy lights and lamps – a created energy to mark each day ending.

My mind wants to do little else except ponder. This feels like a luxury in a time of crisis.

*

On another late night, I end up back on Ngram, preoccupied with understanding my inability to rest.

Looking at the graph again, I notice the space between ‘grief’ and ‘rest’. Closeness does not equal relationality, and yet it is as if they are lying next to each other, bodies closing the white gap between them, draping their blue and green bodies close, falling asleep.

Sources and Reading List

Etymonline, https://www.etymonline.com/

Google Ngram, http://books.google.com/ngrams

Tom Melick, A Little History of Fatigue, Rosa Press, 2021

Chi Tran, I occupy space, which is to say, I am always grieving, IRL Press, 2017

Jack Underwood, A Year in the New Life, Faber & Faber, 2021

This No Compass edition is supported by Multicultural Arts Victoria, as a part of the 2022 Ahead of the Curve Commissions.

Thumbnail photo by Ketut Subiyanto from Pexels