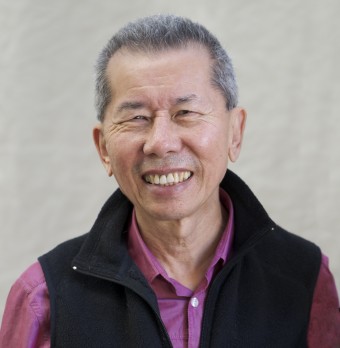

William Yang is a third-generation Australian Chinese artist whose extensive practice includes beautifully poetic monologues set together with striking images, which often examine issues of identity. Here, Sarah Gory continues her interview series with this Queensland-born artist for our special collaborative edition.

William Yang is a third-generation Australian Chinese artist whose extensive practice includes beautifully poetic monologues set together with striking images, which often examine issues of identity. Here, Sarah Gory continues her interview series with this Queensland-born artist for our special collaborative edition.

—

The moment I got teased for being a “Chinaman” at age six was a defining moment in my life. The only person I found who wrote anything about this was the black American writer James Baldwin who said at the age of around six a child realises that there is a difference in race. In my case I went into denial that I was Chinese at all. I felt uncomfortable about the subject as I identified with being Australian, white Australian. I was banana – yellow on the outside white on the inside. When I came out as a gay man, this politicised me, and I realised that being visible was also a political act. There will always be people who are biased against you, but it is important to be who you are in a public way. Strange, being gay is something I could have hidden, but being Chinese was something I could not. I came out as a Chinese twelve years after I came out a gay man. I see the process as similar, in one case one’s sexual identity is suppressed and in the other case ones racial identity is suppressed.

I guess I am different from the mainstream in many ways, a gay Chinese artist, and these ideas of difference, of being other, are a big part of my work. I guess I don’t like rigid points of view, and often my work challenges the stereotype. “Other” is generally not understood or feared, and I try in my work to bring an awareness to it. I support diverse cultures, I would encourage people to be inclusive. I identify as queer which embraces different sexualities.

I found I fitted in to various communities, the alternative, hippy community, the gay community, the artistic community, and at times I have had ambivalent feeling about my own family. I just go where I feel comfortable, and where there is mutual respect. The Australian Chinese community is one of the latest communities into which I feel I am making roads. I have felt they have had a problem with me because I am an out gay man, but this year I was a cultural ambassador for the Chinese New Year Festival, which surprised me.

“Home” can be anywhere I belong or feel I fit in. In the case of Queensland it is the place where I was born and grew up. I was formed by Queensland, in the dry, sparse country around Dimbulah. Landscape is present in my idea of home. But I think everyone also has to leave home, in the metaphoric sense, to become one’s own person. So when I left Queensland I was leaving both family and the landscape. It was easy, because of the times – the era of the counter culture.

“To which I can never return” refers to a quote from Heraclitus, although many people have said similar things, “No man steps into the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” And that’s about an ever-changing fluid Universe. I did keep going back to Dimbulah, North Queensland, the place of my childhood, expecting it to be the same. I never recognised it. Yet strangely I went to a place where I’d never been and there I found the Dimbulah of my childhood.

I still have relatives living in Brisbane and I am bound to them by blood. That’s quite a strong bond. When my brother died they helped my pack up the house and I formed a strong relationship with them over that. I felt I had a role in the family. But we sold the house at Graceville, so a physical home doesn’t exist anymore, but that fits in with my philosophy that the universe is fluid, and the world and our situation in it changes all the time.

“As I see more of Scott, I guess I am appropriating his family’s history,” is a different thing. When you are with another person you absorb their life and their history, especially their family history when you meet their relatives. Scott comes from pioneering family and I am experiencing the country from a different point of view. When he says, “Great Uncle Frank planted that strand of flooded gums to stop the land slipping into the gully,” it throws the strand of trees which I originally thought were always there, into different light.

—

When I started off as a freelance photographer in 1974 it was a way of paying the rent, and I found I could survive better than I could as a playwright. I struggled for 15 years doing jobs for other people, but when I started to do performance pieces in the theatre I found I could generate enough money through my own projects to survive. That was a big turning point because I could focus all my energy on my own projects and so I became more productive. The performance pieces gave me a narrative frame on which to hang my images. I continued to make prints for gallery exhibition and I used the narrative as text written directly onto the photographic prints. This hand written text has become my trademark.

My work begins with the image and everything develops from that. I use various combinations of still image, spoken word or text, and music in my pieces. For the past four years I have been making films of my stage performances; not just filming a theatre performance but reimagining the works for small screen. The mediums of live performance in theatre and performance on screen are totally different and making the films has been a complex and fascinating, creative experience.