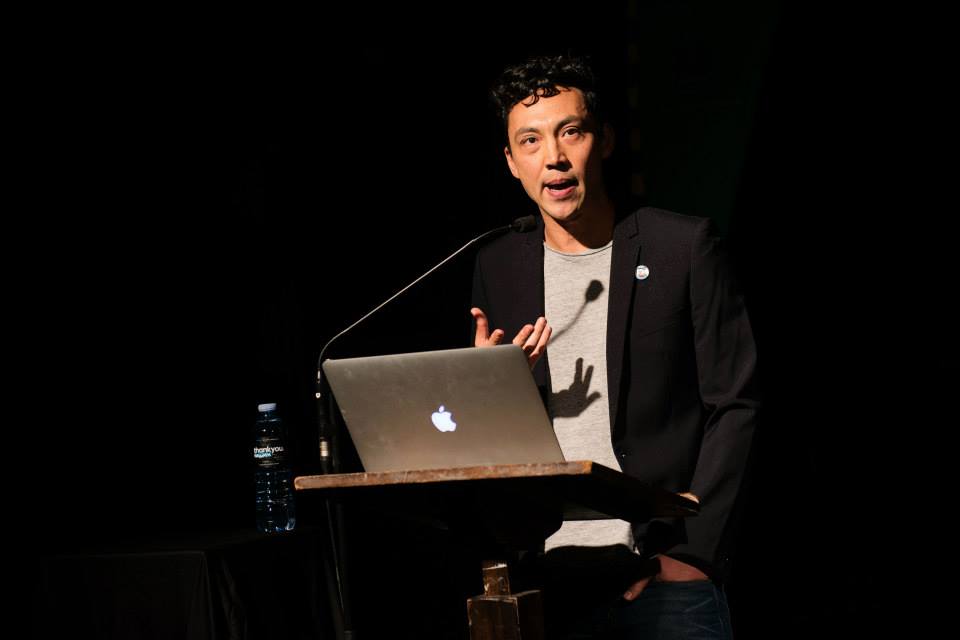

As a part of the BrisAsia Festival event, Yum Chat, Quan Yeomans of the band Regurgitator, gave the following key note address, providing just enough f*cks to kick the evening off perfectly.

For the mild of heart, we have have made some small editorial amendments to this transcript of his keynote address.

Obviously, they’ll fool no one.

Wow. That’s a whole lot of Asians right there!

That may be more Asians than I’ve ever seen in one room in this country outside my favourite Szechuan restaurant.

It’s like an Asians anonymous meeting or something? I feel really nervous about this… So I want to start my talk by asking you all to take a few moments to really just focus on your own genitals. Just to take a little of the heat off me.

That’s not really appropriate is it?

Now, keynotes….

Obviously I’ve never really done one of these before so please forgive me if I f*ck it up… any more. To begin I’d like to thank you all for being here and thank the festival organisers for inviting me to speak. Secondly I’d like to apologise to them and you for wasting your time and possibly offending you whilst wasting it.

I only really said yes to this because of the opportunity to meet Michelle Law of whom I am a big fan. Unfortunately it seems we have absolutely nothing in common. But seriously, meeting people is incredibly important. Possibly the most significant thing outside the actual physical act of creating whatever it is your creating. Hell, it may even be more important!

I can’t really stress this enough because to be honest, just based on my shitty education and crappy creative output alone, I have absolutely no other explanation for how the hell I could have possibly got to where I am today. For those of you who have no inkling of where I am today apart from in this small dark room talking at you, or why this information is even relevant, I will surmise my identity by saying that I’ve played in a touring rock band called Regurgitator for over 20 years. That band’s outrageous fortune has kept me in clean teeshirts for almost the entirety of my creative life.

For that I am very thankful.

In an attempt to make some sense of why a career like mine may have happened at all, I will, as quickly as I can, pick through some of its backstory; hopefully just enough to reverse engineer it to the point where some causality becomes apparent before your boredom does. I place a lot of what happened down to Serendipity and as every one knows serendipity can come in all shapes and sizes. Mine took the form of a skinny dreadlocked, tribal tattooed, rock n roll stoner dude. He was the catalyst of my career and had we not crossed paths my creative life may have never been.

We first met randomly in a forest near Mapleton at a hippy’s dome house party in 1994. That night after stupidly mixing booze and marijuana I found myself carefully licking the leaves of a small shrub next to a makeshift sweat lodge setup on the shores of one of the property’s dams. My memory of the meeting is understandably loose but I believe that while I was busy becoming intimately acquainted with this shrub, a thin merman with writhing worms for hair emerged from the depths of the water and asked me if I felt like jamming in the jam room.

I was like: Sure, If you can help me find where I left my legs, I can do that.

There is no way I could ever tell you exactly what that inebriated funk improv sounded like but what I can tell you is this – it was almost certainly god awful. At that time Benjamin (the merman) was playing bass guitar in a metal fusion band called Pangea, who were well established locally. When I wasn’t busy noodling on my guitar with a bunch of lunatics in a rough outfit called Zooerastia, I was furiously masturbating in the basement of my Vietnamese mother’s home.

Zooerastia’s bass player was an old high school mate called Matt. Matt loved Devo and the Dead Kennedys. The singer was a volatile punk anarchist woman with a shaved head called Vic. Vic was heavily pierced, often wore well loved We are All Prostitute shirts and volleyed scowls so readily and seemingly indiscriminately, it was almost impossible to guess what her real mood might be.

The drummer was a Rock ’n’ Roll Circus juggler called Derek who was so rake thin he seemed like a head planted atop a stack of ab bricks, while his long spidery limbs like minions who followed him around constantly dancing beside him. Though a brilliant, seasoned performer capable of insanely dexterous feats Derek was for some reason so nervous about his drumming ability that he invariably threw up into a backstage toilet every single time just before we were due to play, even if it was only to three or four bar staff, which was almost always the case. We rehearsed reasonably regularly in Derek’s greasy old warehouse space in West End on Fish Lane. All we knew was that it had to be impossibly fast, technically ridiculous and dripping in vitriol. It was a spectacle of noise if nothing more. Now, Zooerastia was inevitably doomed but there is no doubt that my experience with this group was key connective tissue in the overall body of what was to become my career.

At this point I have to talk a little bit about my mother.

Without her none of this would have really happened. Not so much because she gave birth to me, guided me single handedly through some of the trickier teen years and then allowed me to make an endless, often tuneless racket in the basement of her house but more because she always had excessive amounts of personal-use marijuana on hand, and every one of my friends seemed to be aware of it.

In the mid 90s, Brisbane’s music scene was very connected. Benjamin the bass player, who I had only spoken to once more since the dome party happened to be hanging out in Paddington with my singer Vic.

They both were hunting for weed and Vic, having visited my house on a few work-related occasions happened to know that my mother would have some, and that she would be more than happy to share it for the company of compelling, young artistic individuals. By then, I was quite used to my friends using me as a pretext to come over and smoke with her, so I was only mildly surprised to see Benjamin pop his smokey head through the basement door to listen to what I was doing with the DBX noise reduction switch on my Yamaha four track tape machine.

That moment was an important one because it marked the beginning of one thing and the beginning of the end of another. The end of Zooerastia’s life, like the end of most bands was marked with increasingly complex inter-band relationships. The heroin use probably didn’t help either. The last thing Vic, the singer, ever said to me whilst leaning out and screaming from the window of a passing powder blue Combi-Van was:

“QUAN SUCKS DEAD DOG’S BALLS!”

That passed as an affectionate farewell from Vic and I carry those words of fondness with me to this very day. Since that day in the basement when Ben had heard me tinkering he had gotten it into his head to try a side project with me and a half Chinese drummer he had played with before called Martin Lee. At that point Martin was actually the only other musician of Asian decent I had ever crossed paths with during my musical outings. Pretty much everyone up until then had been white.

I was intrigued by his ethnicity, largely because I knew right away he was not the typical head-down-in-books, straight-arrow, family-first type of Asian I’d brushed up against in school. He’d been raised in the back of his father’s Chinese restaurant, then set loose to play drums with punk bands around America in his early teens. Martin’s inked skin seemed like a page torn out of a dark book of Chinese magic. I was immediately intimidated. I knew I didn’t like him but a part of me wanted to be like him.

After a few rehearsals with Martin and Ben underneath mum’s house, it became clear there was something worth pursuing further. Through Martin’s friendship with drummer Jon Coghill we started sharing a rehearsal space with the then fledgling Powderfinger on Anne street just above Galaxy Records in the city.

It wasn’t long before Ben introduced booker/manager Paul Curtis to us. Paul almost instantly understood the vibe of the band and started looking for live avenues for the odd, somewhat different racket we were making.

Around that time I was doing a sound engineering course at the SAE. I recorded about 5 tracks for the band and thanks to Ben again that became the demo that found its way into Warner A&R guy, Michael Parisi’s hands. Paul got us our first gig, an Amnesty International show at Albert Park. We played the only four songs we had twice. After the show someone there asked if we could play the Triple Zed Market Day the following week. Then, based on his own excitement and the response we were eliciting from crowds, Paul secured us a series of critical supports that put us in front of a lot people. Soon afterwards Paul began managing us. Within 6 months of our initial jam underneath my mum’s house we had signed a 5 album deal at Warner and the rest is well… the rest.

20 years go by and I’m finally asked to talk at this event about it all.

I was of course asked to talk at this event not just because of my creative career but also because of my Asian heritage. To be honest I felt like I was always gonna let the team down a bit on this one because as a ‘Halfie’, and I’m not sure if this is a common thing but when it comes to ‘Asian-ness’ I’ve always felt like a bit of a fraud, a chameleon, a changeling, obsequiously blending into which ever ethnic background seemed to be appropriate for that particular social situation.

This may have been the reason that for as long as I can remember the idea of race and culture has struck me as a largely superfluous and irrelevant; an almost archaic one. Over the years I’ve cultivated a similar attitude towards gender, religion, politics and sport. They all seemed like cheap constructs, human cliches, handrails for the feeble minded.

I was never built to be a team player. I felt genuinely misfitted even though I was strangely blessed with this gift of being able to blend in.

I was The Occasional Asian.

I used to think I might have been bridging cultures. One foot in the Anglo Saxon tradition of my father, a fifth generation caucAsian Australian with a dram of Irish and a dash of white guilt; and one in the Asian-ness of my mother, a strong Vietnamese woman with complex connections to her heritage but in reality I think it placed me in a kind of cultural no-mans-land caught between the Australian-ness of my father and the Vietnamese-ness of my Mother, neither of which seemed applicable and thankfully neither of which were ever shoved down my throat by either parent.

So instead of being cradled by a sense of nationality I felt nurtured by a ‘notionality’. I identified with my own notional state where my sense of self through imagination was the only cultural ‘heritage’ I was truly invested in understanding and mapping. Because of this, it’s not honest for me to talk about how my Asian-ness has played a part in my artistic life without admitting that on a day to day level, it seemed to be a very superficial one.

It did however turn out to play a secret but fundamental role. It fostered the growth of a unique, uninhabited vacuum for my artistic mind to exist in between cultures. I recently ran across an article by self development writer, Mark Manson, which helped me quantify the value of such a vacuum in my situation as a creative person.

It’s entitled – ’The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck.’ In it, he postulates about being given a finite amount of F*cks, I guess kind of like a bag of F*cks at birth, which it is then up to you to disperse at your own discretion. He states the importance of choosing to give your biggest F*cks away with care and how that choice can vastly alter the direction of your life.

For example by giving all of your F*cks away willy nilly you become something like a F*ck-less wraith. Hollow and constantly peeved at all the small inconveniences that make up day to day life. You could also look at it like you were a federal reserve of F*cks, constantly printing an endless supply of little F*cks with your 24 hour F*ck press, and carelessly circulating them out in the world, thereby devaluing the F*ck exponentially. Pretty soon you’ve got the Vietnamese Dong of F*cks and you have to push around a wheelbarrow full of F*cks with you just to get through an average day.

But i digress.

One of the main point’s of Mr Manson’s article which resonated with me was this – ‘NOT GIVING A F*CK DOES NOT MEAN BEING INDIFFERENT; IT MEANS BEING COMFORTABLE WITH BEING DIFFERENT.’ It’s really the best description of the slippery concept of ‘Cool’ that I’ve read. It resonated with me because I’ve often looked back at periods generally considered the least shit in our band’s history and always been amazed at how little of a f*ck I appeared to give.

I look at photos of me on huge stages in ’96 sporting torn off denim hot pants, cracked paedophile glasses, terribly arranged hair, grotesquely unflattering facial expressions – obviously so caught up in not-giving-a-f*ck it is jarringly bizarre for the now somewhat vain, ruined by success version of me to look back at and behold. I didn’t look cool but I WAS.

If my occasional Asian-ness was of any aid to me it was in that endeavour. It placed me in a position where I was aware that I was different to those around me and taught me not to give a f*ck. It forced me to quietly inhabit the cracks in between culture and in those cracks form my own identity out of noise and teen angst. It made me a confident outsider.

Don’t get me wrong though, I’m not anti-culture. I’m constantly in awe of the consequences of Human Endeavour. I find it everything from wildly fascinating to strangely absurd. Diversity and constant cross-pollination is a beautiful thing and I’m totally prepared to wave that particular banner, just not any national, racial, gender specific or religious one.

As that kind of flag, I think the band performed pretty well. We were an eclectic looking bunch who were astonished that a whole bunch of people seemed to like being yelled at by us. There was a surreal absurdity to it all that I can never really fully explain. I do feel however that it might be disappointing for those of you interested, to know how little my Asian-ness really influenced my art directly and in a way I am a little sad that I wasn’t more open to explore its possibilities.

There were a few things that snuck in there in the beginning of the band’s life though. I had studied the Sitar with a Pundit in Sydney, on my father’s recommendation, and for a while I would come out onto the stage, sit down, plug it in to a Marshall stack and open the set. Unfortunately whenever we took the thing out on tour, by the first week its large resonating gourd would be smashed into a million pieces by heartless baggage handlers and it would limp home to be re-glued.

My mother also brought back a couple of cool but odd Vietnamese instruments one time after a trip. A custom made hand harp-thing called a Chieng, I think after the sound it made, and a sick-sounding reeded, oboe-like instrument, both of which were used in the studio and did stints on a couple of tours.

I think the most impressionable Asian experiences the band absorbed however was when we actually got a chance to play there.

Japan was our first foray into the other-worldliness of Asian audiences and it really was such an insanely different experience to playing at home that it captured some of our favourite memories of touring life.

None of us had ever experienced the level of fandom in that place before and it was bizarre. Little crowds of fans, girls and boys would follow us around the city after the show, carefully shadowing us from respectful distances of around 20 metres like a bunch of tiny, poorly trained CIA agents. They made us thought-provoking shirts and dolls, and were generally just so sweet it was surreal.

The music company culture was also really weird. I remember being led into an office by one of the East West reps to meet the marketing team. It was a tiny room full of small school desks piled high with chaotically stacked papers. When we entered everyone quickly got up bowed and then started clapping at us. We stood there awkwardly for a second, bowed back and then filed out again.

I think the sheer alien-ness of it all gave me the same sense of observational freedom I had gotten used to from being in the band. I didn’t have to identify with any of it I could just let the oddness of it flow over me from the impervious bubble of the group.

I know I’m speaking to a room full of Practitioners, some experienced and some also just starting out. So I feel I should touch a little on creative process. Like most practitioners I can tell you a bit about my process but only the parts that I’m actually aware of, and its the other 95 percent of the thing that causes Woody Allen to explain skill sets as complex as Film Directing with flippant remarks like “Either you have it or you don’t.”

The truth is if you’re not lost in the ‘process’, whatever applicable one that is, then chances are you’re not producing your best work.

Not giving a f*ck definitely helps with the being—lost-in-it-all part because it encourages you to take risks, avoid over-contextualising your work, and it may assist you in abandoning your art before you kill it with over-iteration.

If I look back on what I consider to be the most successful periods of my artistic career, I see a amateur in love with the technical process, an outsider not caring about result because I had yet no notion of mass acceptance or rejection. I also see a naive kid eager to define my understanding of the world by what I was doing artistically and then attach my ego to that understanding. Now, if you happen to find yourself in anything like that position then I urge you to carry on. It is literally the only thing I can suggest.

Over the years I’ve almost never felt like it was my place to advise other artists about things like their careers or practice, and if i ever did I was even less aware of the impact that that advice may have had.

I mean who the f*ck is anyone to say? Most artists don’t even come close to understanding the relationship they have with their own art let alone the relationship another artist has with their own.

But there was this one time when Darren from a band called The Avalanches did make a point of cornering me backstage at a festival we both happened to be playing at. This was well after they had by far eclipsed our successes on an international scale.

This is roughly what he said:

“When we were a young band supporting you guys this one time, I remember asking you what you thought we could do in order to get into a position like you guys?”

Apparently I paused on the question momentarily, shrugged and said “Just keep doing what you’re doing.”

Then he said, “I always really appreciated that.”

Looking back on it now I realise that could be just about the lamest f*cking advice you could EVER get from anyone!

And that’s why I’m now going to impart exactly the same advice to you.

Use your cultural backgrounds, abuse them, rebel against them or infuse them into the fabric of what you create. It doesn’t really matter.

The artistic experiences that you’ll offer will be unique because of who you are and how your cultural heritage has shaped you. Allow it to make an outsider of you or at least give you an outsider’s perspective.

Just keep doing whatever it is your doing until you’re so lost in what you’re doing you don’t give a f*ck about anything doing else any more. Then keep going.

Then maybe, just maybe serendipity will guide you to the catalyst of a career you love and then you’ll end up making a ridiculously long keynote speech at an event like this one.

Thank you!