Digital Collages + Text by Leyla Stevens.

i.

Some time ago – I’m not sure when – I stopped being a photographer. It used to be that the camera was a constant device for me, and I can trace my own trajectory as an artist through the various cameras I have owned over the years. But more and more the camera feels like a burden, the photographic moment no longer worth seeking out. Yet I continue to call and think of myself as an image-maker.

I’ve been reflecting lately on why this happened. In many ways, there is a clear link to the fatigue of digital imagery, which has shifted the value of the photographic moment – to being a citational moment. And by this I mean that now when I take a photograph, I am aware that this image most likely already exists: accessible online, dispersed and shared numerously.

But this is not a conversation on analogue versus digital technologies. Nor is it about nostalgia, I think.

ii.

When my daughter was born I had no time or energy to pick up my camera, something I regret. There is an intensity to those first few weeks after you give birth. In labour you become an animal. Your instinct throws up desires and knowledge buried deep in your body. And this altered state doesn’t quite leave you immediately after. It made me realise photography for me had become fixed in the category of work, and in that time, I had no capacity for this kind of labour.

iii.

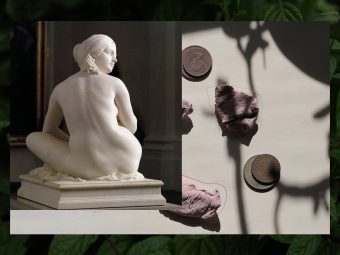

One way to sidestep this problem of photography – the question of its value, in capturing a moment – is to take comfort in its inherent unoriginality. An image can be reproduced over and over until it loses its initial meaning. Like when you say a word too many times and it loses essentiality and appears as a foreign shape on a page. There is a beauty in the multiplicity of photography, in its nature to be repeated and to be interpreted anew. The value of the image becomes a shifting performance over time.

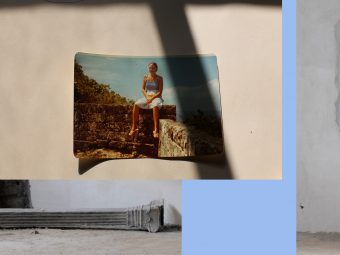

Having lived most of my life along a coastline, I tend to get disorientated when moving through inland cities. My instinct when arriving some place new is to locate the nearest body of water – river, lake, canal – and orient myself this way. When I look back at the way I’ve moved through unfamiliar places through photography, I realise that I’ve been taking the same image over and over. There is a repetition of subject matter and of framing: a cataloguing of the same type of things but in different places.

iv.

Much of how cultural space is mapped in Bali tracks the flow of water across the island, from mountain springs in the north, trickling down to rivers, streams, subak irrigation systems and eventually the ocean in the south. The symbolism of this directional line maps a connection between the sacred north (kaja), which is aligned with mount Agung, and the profane south (kelod), which is aligned with the sea. This north-south axis is a trajectory that governs the design of a village, the architecture of the family home and a meridian line that runs through the body, from the head to the feet.

But these cardinal directions are also relative to Agung, whose true position lies in the north-east of the island. So if you live in the regions north of the mountain, kaja becomes south and kelod lies north towards the Bali Sea.

I’ve come to appreciate this fluidity of something as fixed as cardinal points. Your orientation, how you navigate place, becomes guided by an unstable mountain (for Agung is a sleeping volcano). Finding your way around becomes an exercise in relativity.

v.

Bend your body towards the earth. Touch ear to ground. Listen for encroaching footsteps. Of crickets clicking. Of distant mountains. Of secret water channels. The sound of one’s own inner ear drum. Like a cave.

(Epilogue)

Your ear is the centre of your equilibrium. It is where your sense of balance is maintained. The inner ear is called the bony labyrinth – scala tympani, scala vestibuli & scala media, which houses the receptor organ for hearing, the Organ of Corti, named after an Italian anatomist.

I remember the last time I was in Yogyakarta. Arriving from Japan, I became sick in the first few days and the lingering effects from this virus was a slight loss of hearing. For weeks I felt I was underwater, only hearing the echo of my own voice.

For those weeks I also experienced a loss of an inner ability to navigate. My sense of balance was off, and in this psycho-geographical sense, I no longer could find my way around. I think now, this is where I can trace to the moment when my camera started to feel too heavy to pick up. And I no longer wanted to take images in the same way.