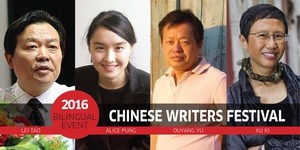

As part of Peril’s coverage of the Chinese Writers Festival, we are reviewing some of the work by guest writers hosted at the festival. First up in the series, language teacher and translator Xia Cui reflects on the some poetry of Ouyang Yu.

Ouyang Yu is a prolific and accomplished poet, critic, translator, editor and novelist. His literary creations have won him multiple grants and awards of prestige, his poems consecutively included in the best Australian poetry collection.

I, on the other hand, don’t read much poetry and somehow had the idea that its grace and subtlety might be well beyond my grasp. Hence I was understandably nervous when asked to review some of his works as part of the Chinese Writers Festival taking place on the 28th of August.

Such concerns quickly went away as I sat down to read Ouyang Yu’s poems and gladly find them frank and accessible. The feelings revealed between the lines are familiar and resonating, as I too am a Chinese living in Australia who, at times, translates and writes, though far less experienced and skilled.

Often raw and alive, Ouyang Yu’s poems are free flowing and the styles of these are unpredictable.

Some are witty:

“15. Sky, an umbrella, but leaks.”[1]

Some are honest, and slightly brutal:

“8. Love you, she said, years ago.”[2]

“38. Lied together, fucked together, parted forever.”[3]

Some are delicately poetic, like The Tree.

Occasionally, he might be bored, or perhaps is trying to be smart:

6-word stories are longer than five.

Yet there are also those that are unexpectedly heavy (Someone), and loaded with complex emotions (Moon over Melbourne).

Ouyang Yu apparently finds poetry in everything, and anything: a misread of book title (A happy misreading), a typo, seeing a breast feeding woman on the street (So nice), the translation of a commercial document full of technical terms (Flowers), his own fetish of the –ish suffix (Fetish), and his creative play with the Chinese and English language.

Being bilingual and an experienced translator gives Ouyang Yu an edge in his literary creations. In his eyes, direct translation itself is poetry. Seeing this happen, I couldn’t agree more.

For example, his poem, China, consists entirely of the direct translation of selected names of river in China. It reads not only smooth and poetic, but also renders native speakers of Chinese, like myself, a new perspective to re-appreciate the poetic-ness of our mother tongue which we so often take for granted. Indeed, as Ouyang Yu writes:

Nothing can be more pleasurably creative when writing, reading and translating happen across the board, and across the genres. [4]

In Ouyang Yu’s works, I see a poet who dances with ease within and between Chinese and English. His authority and ownership of both the languages is impressive. Whichever language he writes in, he owns, exploits fully his bilingual advantage, does whatever he feels like to his creative satisfaction, and apparently has great fun while doing so.

Along with reading Ouyang Yu’s poems comes another pleasant find, his views on writing: “write anywhere and anyhow”.[5] Indeed, he can write more than 45 poems over just two weeks, and when questioned on the perfection of these, Ouyang Yu’s response is a gift card quote: “If you keep refining shit, would it become non-shit?”[6] So instead it is, as Ouyang Yu says beautifully:

To capture the spirit of the moment, like a falling star, like a flying butterfly, like a passing whim, a poet has to be constantly on the alert. [7]

While I’m a little offended by the shit-refining part, as that’s basically what I do all the time, his idea of perseverance holds true to any of us who write to create and hence at the mercy of inspiration that arrives and leaves as it wishes. To best our chance of catching it next time inspiration pops by, let’s write anywhere, and anyhow!

Then, last but not least, and quite unexpectedly, I was thrilled to find something from Ouyang Yu that I could perhaps borrow and use straightaway, his outlook on self-identity, or to be more precise, his response to the various versions of identity applied on him: “After a while, though, seeing that people continue to apply whatever terms they’d like to when describing me, I have given up on feeling uncomfortable but just let things go as each makes sense on its own, capturing only part of the whole thing identity-wise.”[8]

Similar to him, I too changed passports; feeling the need to justify this choice at times can be slightly annoying, and I’m yet to come up with a response that I could comfortably pull out when I need to. Reading Ouyang Yu’s response expressing a thought similar to mine but with non-confrontational confidence makes me feel less anxious, and perhaps even empowered. Before I come up with my own, I may just borrow his.

So here I am on a wintery weekend of Melbourne, discovering the grace of poetry expressed with passion and genuineness, and more.

[1] Ouyang Yu, Short Short Stories , in Peril Magazine 22(2015).

[2] ibid.

[3] ibid.

[4] Ouyang Yu, Ways of Writing, Reading and Translating: Genre-Crossing in the 21st Century, in Peril Magazine 14(2012).

[5] ibid.

[6] ibid.

[7] ibid.

[8] Ouyang Yu, Rotten, in Peril Magazine 15(2013).