To play or sing a rāga is to draw from an Indian classical melodic framework that has no direct equivalent in classical European music traditions. What would it mean to partake in an art form so old, complex and intricate that it has no precedent in the Western world? What would it mean to be the precedent?

That’s what struck me as I watched a number of the performances at Sangam. I am someone who writes, speaks and dreams in an imposed colonial language that isn’t mine, that isn’t my Dravidian mother tongue whose roots stretch as far back as the sixth century. It was powerful to watch artists decolonise and decompose white supremacist patriarchal frameworks in an artistic language that had never been anyone else’s but theirs.

Sangam, the Sanskrit word for confluence, describes the occurrence of two or more flowing bodies of water joining together to form a single channel. In the case of Melbourne’s first arts festival by South Asians for South Asians, renowned dancer and scholar Dr Priya Srinivasan, acclaimed veena artist and singer Hari Sivanesan and award-winning artist, composer and educator Uthra Vijay co-curated a platform in its name. Sangam, which ran from 21–23 November at Bunjil Place and Dancehouse, brought together thoughts, ideas, performance and dialogue from intergenerational, LGBTQIA+ and multidisciplinary artists internationally from India and artists in South Asian diaspora communities in Melbourne.

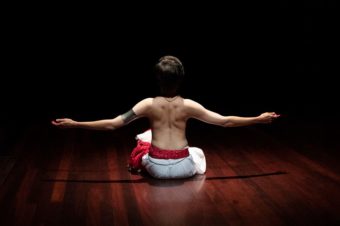

Birrarung: Dada-Desi, the festival’s showcase evening of 17 artists, was co-curated by interdisciplinary artist and researcher, Nithya Iyer, and writer, comedian and performer, Vidya Rajan. In one of the performances, professional dancer Shriraam Theiventhiran took to the stage, resurrecting an ancient Indian performing arts treatise from 200 BC called natyashastra to explore his feelings of dislocation growing up as the only South Asian in his white western Melbourne primary school. His eyes dramatically darted back and forth in unison with the beat – a hallmark of traditional Indian dancing where the expressions on a dancer’s face are as crucial as what they’re doing with their arms, legs, feet and hands. Using energetic yet precise movements, Theiventhiran’s spoken word and contemporary take on an ancient artform was simultaneously stirring and spellbinding.

Carnatic singer Arjunan Puveendran sang an original composition in Tamil about Sita, the heroine of sacred literary epic Ramayana who was cast out by a patriarchal society, in a feminist retelling of the tale which didn’t leave the revered Hindu deity Rama beyond censure. His impressive vocal undulations in the reethigoula rāga were accompanied by the rhythm-setting beats of Nanthesh Sivarajah playing the mridangam – a 2000-year-old double-sided drum from Southern India – Bhairavi Raman playing the Carnatic violin, and classical bharatanatyam dancer Kersherka Sivakumaran inhabiting the role of Sita with her stricken gesticulations to Rama and the fate that had befallen her.

This question of who has permission to access an artform and what they can do within it was brought beautifully to the fore by Bangalore-based dancer Masoom Parmar. On a panel revolving around the dichotomy between tradition and experimentation, he questioned his place as one of the few Muslim practitioners of the Hindu dance bharatanatyam.

“I am using bharatanatyam’s vocabulary to narrate the stories of now. Within this form, there is scope to say things beyond worship of god. But when does a classical form stop being a classical form? Who says what it is? Do I have the right or permission to access this art form?”

When he took to the stage, Parmar foregrounded his first dance in the context of the day his entire life changed – 27 February 2002, the day of the Godhra Train Burning where 59 Hindu pilgrims were set alight inside a train in Gujarat. The incident was the catalyst for the Gujarat riots which resulted in a widespread loss of Muslim and Hindu lives. Meanwhile, over 1,000km south in Bangalore, a young queer Muslim boy was forced to hide the fact that he held his Islamic faith close while practising a Hindu art form.

Parmar may have been talking about bharatanatyam, but his thoughtful, ceaseless interrogation of who has the right to access the stories of others has been a lightning rod for heated debates over ownership, responsibility and appropriation in Australia. This has rangeds from the Horne Prize’s since-rescinded 2018 criteria that ruled out “writers purporting to represent marginalised people without lived experience” to howls of outrage from white judges, to the recent cancellation of a comedian’s show at the 2019 Melbourne Fringe Festival amid accusations that it was yellowface, which has prompted calls that “call-out culture is killing comedy”.

Because it didn’t centre whiteness, Sangam was able to platform nuanced discussions on the intercultural exchange that can happen between people of colour in specific contexts where the white gaze is simply irrelevant. In Parmar’s case, this was India’s socio-political, historical and geopolitical divide between Muslims and Hindus. As the festival sought to create the space for Black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC) to work together without a white mediator, Wurundjeri Elder Uncle Ron Jones’s Welcome to Country drew parallels between certain words in Tamil and ancient Indigenous languages, proving that BIPOC’s engagement with one another pre-dates whiteness.

To be without the fear of a white audience member piping up from a place of entitlement at the end of Sangam’s panels was a source of palpable relief. Only a week later, I attended a mainstream literary event where an audience member asked a question containing these two phrases: “As an Anglo Aussie, I was quite fascinated by…” and “This isn’t a question, more a comment.”

________________

Sangam wasn’t part of an umbrella South Asian festival such as the Jaipur Literary Festival, which descended upon Federation Square in February 2017 under the expert curation of Jasmeet Sahi and Lisa Dempster, but a standalone festival – the first of its kind to gain funding of any sort.

I didn’t realise (foolishly, in hindsight) how much Sangam would disrupt preconceived notions I take for granted on what it means to be in a performance space in Melbourne, how it feels to perennially be the minority. In his piece ‘Safe White Spaces’, Filipino-Australian artist and curator Andy Butler – who also moderated a panel at Sangam – takes aim at the institutional whiteness across the arts community.

“It’s very noticeable when you’re not white – when your body or cultural background is thrown into relief because it can’t be assimilated into unmarked whiteness and its values.

“To me there’s a difference in feelings of openness and joy as the burden lifts from you when you walk into a room in the arts community and white people are the minority.”

There’s no other word but joy to describe how I felt stepping into Dancehouse, a performance space in Carlton, a suburb that was synonymous with working-class communities before post-war ‘studentification’. The swathes of white baby boomers who typically crowd into inner city performance spaces had been supplanted by aunties jostling for a seat in their impeccably tied saris, patting each other on the back as they exchanged stories with careless abandon. What I’d expected to be a sea of Doc Marten-clad feet sticking out conspicuously beneath ultra-skinny black jeans were instead open-toed sandals and flowing salwar kameez pants. I don’t know why I expected this audience to be predominantly white, but I did, and I didn’t realise how much I needed it not to be until I stepped into Dancehouse. Dressed in the arts uniform of Gorman, I was a minority in a different way altogether.

The few white audience members attending Birrarung: Dada Desi were relegated to the periphery, occasionally the butt of host Vidya Rajan’s jokes in one of the best instances of punching up. Collective in-jokes revolving around Whatsapp family groups, beef-eating puns and being a coconut (or an oreo in comedian Pedro Cooray’s case) weren’t translated for their benefit. The reversal in power relations was both intoxicating and refreshing. The only joke that had overwhelmingly white audience members tittering was when Carnatic violinist Maiyurentheran Srikumar expertly played ‘cups’ from Pitch Perfect, a classic white text.

But I’d be lying if I said I felt completely at ease in this audience. My connection with my Indian heritage is unequivocal yet harder to tangibly trace. I felt an absence of the ability to do the things many South Asians in the room took for granted – the ability to tie a sari, the space to hold one’s mother tongue in the same mouth that speaks the coloniser’s language. But I recognised myself in Sri Lankan-Australian poet Sumudu Samarawickrama’s mournful question: “How much of the sublime or the subliminal have I missed because I haven’t understood Sinhala as well as a native speaker?” I resonated with Pedro Cooray’s apology as his accented Australian twang rolled inelegantly around the new Sri Lankan Prime Minister’s name. I saw the winged pattern of my everyday eyeliner replicated in the kohl-rimmed expressive eyes of dancer Priyadarsini Govind. I chuckled as the Indian friend I was with echoed my inability to differentiate between the veena and the sitar.

________________

Dr Srinivasan is fascinated by the idea of how to be both: both classical and contemporary, traditional and experimental, academic and artistic, theoretical and practical. Dr Srinivasan made the choice not to make a choice between her practice as an acclaimed Bharatanatyam dancer and her work as a scholar committed to questions of migration, female labour and art. This refusal to neatly shoehorn herself into arbitrary categories and to continue practising her art in oft-challenging conditions is the underlying ethos behind Sangam.

This rebellion feels all the more pertinent for BIPOC creatives who are often boxed into producing art about “the trauma of white supremacy, immigration and imperialism” and whose artistry, intellect and imagination are often overlooked or seen as an extension of their one-dimensional selves rather than a painstakingly perfected craft. Tamil writer Meena Kandasamy talks about how impossible it was for critics and fans to engage with her award-winning novel When I Hit You as a piece of art instead of a mere re-enactment of her life.

“By treating it as memoir, people were overlooking the artistry…For me, the artistic enterprise is: ‘I’m going to tell you a story’, a narrative that has been shaped. It’s not therapy.”

The artistry on display at Sangam was unmistakeable, directly countering what Dr Srinivasan calls the “deep misconception that in order to be contemporary in Australia, you have to do Western contemporary dance or theatre”.

“If you are perceived to be engaging in ‘ethnic’ forms, you’re not considered ‘high art’, you’re not considered contemporary. I am working against this idea, and this has been the root of my activism since moving back to Australia,” Srinivasan said in an interview with Liminal Magazine.

But the elevation of non-white artforms into something deserving of the moniker ‘high art’ wasn’t the only reason Sangam was revolutionary. The significant absence of hierarchy was another. Dr Srinivasan and Vijay were responsible for delivering Sangam, but they took to the stage themselves on the last day of the festival, seamlessly juggling their curatorial and artistic selves. They performed their work in progress, ‘Radhika and Muddupalani’, alongside internationally acclaimed bharatanatyam dancer Priyadarsini Govind and vocalist, composer and violinist Lalgudi Vijayalakshmi. This excerpt made visible the since-erased literary contributions of acclaimed 18th century Telugu-speaking poet and devadasi Muddupalani. The fact that the piece wasn’t complete challenged the idea of perfection in its very performance. We often forget that curators have their own artistic practices that extend beyond nurturing the talent of others, that curatorship is never a static, all-encompassing identity.

Dr Srinivasan also continuously sought to redefined the terms of engagement between audience members and performers. She beseeched everyone attending a particular panel to bring their chairs down from the mezzanine level and sit in ‘yarning circle of engagement’ with the panellists. This new mode of interaction between audience members and artists worked well in a context where no one was asking the artists to perform their trauma or appease their guilt. This is not to say that it worked well because there were no white audience members (there were), but because it was an exchange rooted in collaboration and mutual respect instead of mining and extraction.

Sangam wasn’t perfect – accessibility was a key concern with no elevators available in the multi-storied building, and panels were held in cavernous timber-lined rooms where speakers’ microphone-enhanced voices ricocheted across the room at the expense of clarity. Everything happening at Sangam had a faint sense of chaos to it – none of the performances started or finished on time, as Dr Srinivasan joked about running on “Indian standard time” which later changed to “European standard time” as the events ran later and later. But in finding new ways to interact with and live with living on unceded Aboriginal land, in exploring the past to create a kinder, more imaginative future, and in reconstituting colonial frameworks to express radical ideas about identity, personhood and belonging, Sangam felt like freedom.