Author’s Note: The term East Asian Australian (EAA) has been used to avoid perpetuating East Asian hegemony in discussions of Asian Australianness

I once met this tech bro who told me that Samsung was just a copy of Apple and their ‘geniuses’. Anonymous, robot Samsung workers merely stole the work off relatable, everyday Zuckerberg-esque men of Silicon Valley who wore hoodies and ate kale salads. With a defiant, unwavering gaze, he told me that Samsung could not be trusted anyway. I knew immediately we were talking in metaphors.

In August last year, the Australian government officially blocked Chinese telecommunications firms, most notably Huawei, from providing equipment to Australia’s new 5G mobile phone networks, on the basis of national security. Subsequent claims made by individuals like federal MP Andrew Hastie stating that “China’s ambitions threatened to erode Australia’s sovereignty and freedoms” point to a rise of Sinophobia imbricated with the emergence of technophobia.[1]

In an image forming part of her latest photographic and video series ‘Oriental Futures’, artist Zoe Wong lies on the floor with her eyes closed, the Huawei logo projected onto her profile.

The red petals of the logo glow, branded onto her skin and moulded into her flesh. Here, Wong’s cyborg body has become seamless with technology, her corporeal form a vessel for Chinese technology. Simultaneously the photograph becomes a visualisation of the fears and stereotypes that are often projected onto East Asian bodies.

These anxieties are part of a culture and history that has been inculcated in the Western popular imaginary for decades in the form of techno-orientalism. Defined by theorists David S. Roh, Betsy Huang and Greta A. Niu, techno-orientalism is “the phenomenon of imagining Asia and Asians in hypo- or hyper-technological terms in cultural productions and political discourse. Techno-Orientalist imaginations are infused with the languages and codes of the technological and the futuristic”. [2]

In Wong’s visions in ‘Oriental Futures’, recently exhibited at Boxcopy in Meanjin, cyberspace (now inseparable from physical space) is imbued with East Asian signifiers. In #3, a computer monitor displays Chinese script, and in #5, advanced military technology is labelled ‘Made in China’. The ubiquitous phrase points to the weaponisation of labour and the myriad of ways in which East Asia, specifically China, is portrayed as a place of menace and military manufacturers.

Whilst Roh, Huang and Niu’s theories are grounded in East Asian American studies, they may be applied to an Australian context. In their book Techno-Orientalism they track the dehumanising perceptions of East Asians in America, concluding that the view emerged in the discourse surrounding early US industrialisation.[3] Similarly, in Australia, many Chinese migrants arrived in the early 1850s as indentured labourers, mere tools in the colonial project, viewed as expendable labour and replaceable technology.

These colonial legacies continue to be espoused in Australia, particularly now in the digital arena. On October 14 this year, the ABC’s programme Four Corners conducted a joint investigation with Background Briefing into alleged ties between Australian universities and Chinese organisations involved in Beijing’s global surveillance. The episode, titled ‘Red Flags’, concluded that Beijing is in fact running a global cyber espionage operation through technology companies.

During the programme, Professor Chen Hong, Director of the Australian Studies Centre at East China Normal University, lamented, “I think it is actually like a witch hunt and is so interrelated to China having been labelled as some kind of threat. It’s no longer Yellow Peril, but it’s Red Peril”.

Wong visualises this Red Peril and its effects on individual people in erasing their personhood and humanness. In #4, an arm extends from the corner, but the skin has been rendered plastic, and silicon veins in the form of electrical wires spill forth. Meanwhile, in #2 a bowl of uncooked ramen waits to be consumed in a sterile environment. These images reflect the portrayal of East Asian bodies in Western popular culture as mere simulacra, ontologically different and ‘othered’.

At the age of sixteen when I told teachers I wanted to write and study humanities subjects, they scoffed. I was copier, not innovator. I was follower, not creator. I was a manufacturer, not a designer. Peers told me to forsake such biological impossibilities.

Their comments were supposedly ‘flattering’, meant to confirm my ‘superior racial intelligence’. However, it was actually part of a narrative designed to deny me full personhood. A narrative designed to keep me apolitical, silenced, and erased. I was to operate on algorithms and formulas, to be stoic and stolid. Impassive and passive.

When faced with the threat of being ‘swamped’ by us, how else to mitigate the threat but to keep us faceless, nameless and force us to internalise political apathy?

Australia’s fear of China is entrenched in centuries of discrimination, with four anti-Chinese bills introduced to Parliament between 1857 and 1861. Not to mention the passing of the Chinese Immigrants Regulation and Restriction Act in 1861, which limited East Asian movement, with only one Chinese person allowed per ten tonnes of shipping. This rhetoric equates East Asians to cargo, things to be imported and, conversely, objects that may also be exported.

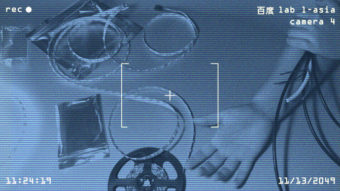

These distrustful cultural perceptions and Sinophobic narratives have taken a new face in today’s technological milieu through fear of Chinese surveillance. Australian mainstream media, like Four Corners, often depicts China as an Orwellian nightmare, an apocalyptic smog-scape. In Wong’s #4, a tableau is seen through the pixelated low-quality lens of a security camera. Evoking xenophobic fears of a Panopticon state, what was merely speculative in science fiction films and novels like Cloud Atlas, seems to be already here. And, even more threateningly, within the fabric of Australia.

As a fifteen-year-old, I watched films like Cloud Atlas and Bladerunner with guilty pleasure. Korea with its fluorescent frivolity, electric elation and digital delirium was reflected back to me from celluloid. Although this was not the Korea I knew or necessarily grew up with, it was now deemed ‘cool’; a place of novelty.

Wong’s photographs are lit in a seductive blue neon, an homage to the neo-noir atmosphere of countless science fiction films like Blade Runner. The incredibly stylised mise-en-scenes speak of the desire and fascination that is simultaneously used to fetishise East Asian culture, both by the West but also too from East Asia itself. Roh, Huang and Niu alert us to the ways that techno-orientalism has in fact been internalised and reified by East Asian countries, looking at how technology has been used to promote Japanese nationalism globally. [4] Therefore, when we look at Wong’s images, it is worth asking: how do East Asians themselves uncritically replicate the same models and aesthetics that are used to maintain a racial hierarchy and order? How much of techno-orientalism itself is authored from East Asian agency itself, and what implications does this have on East Asian Australians?

Dawn Chan on her essay on Asia-Futurisms, published in the Summer 2016 issue of Artforum, observed that throughout art history, East Asian artists have indeed celebrated the liberating potentiality of technology. [5] Artists like Nam June Paik, recognised as one of the first artists to break the boundaries between art and technology, to Lee Bul and her cyborg series, were hopeful about the future of technology.

Lee Bul’s works have been oft-discussed in relation to Donna Haraway’s seminal 1985 essay ‘A Cyborg Manifesto.’ In this work, women are imagined as inseparable from social and technological machinery, and therefore radical and resistant – embodying alternative social and political possibilities.

2019, projected still image, size variable.

But how do Haraway’s theories apply to groups and people in the diaspora who are already seen as ‘cyborgs?’ What can we learn from Haraway when the link between the East Asian body and the cyborg has been used to consolidate racial hierarchies? When the cyborgian associations have been made in ways that de-humanise to justify violence and withhold individuals from enjoying the full gamut of human emotion and experience?

Cyborgian logic showed me that all the contrived terms of my life are constructed. During my most formative years, while in school, it was made clear to me I was a quota, and it was expected that I would aspire towards ‘perfection’ in academia, and in general. In the robotic sense, my value was entirely quantified.

Perhaps, then, it is important to recognise the distinction between robot and cyborg. Whilst robots are automated and programmed to comply, cyborgs are a combination of living organism and machine. As Haraway writes, the cyborg was “created to transcend systems of racism, sexism and capitalism by destabilising borders between ‘self and other, autonomous organism and deterministic machine”. [6] Perhaps there exists a potential for liberation in undermining the logic of the robotic in favour for the cyborg. As Chela Sandoval writes in Methodology of the Oppressed, it is important to re-appropriate what it might mean to be a cyborg, and to define the cyborg away from methods of obedience. [7] Rather, Sandoval provides a methodology for cyborgs to gain autonomy under various systems of oppression, especially racial oppression.

Cyborgian logic taught me to be aware of the cracks—the glitches—in the structures around me. My awareness of the falsity of these structures showed me that I do not need to obey – that I am capable of resistance, and allowed to be humanly imperfect. To be careless, selfish and jealous, and to love, to have compassion and the ability to transform. There is freedom in disobedience. In the flicker of a glitch I see a glimpse of a new futurism based on a narrative of hope.

Wong’s video #1 depicts a photograph of Wong as a caricature of an East Asian woman with painted white skin and chopsticks in her hair. Yet the pixels on the screen glitch and distort her face. This glitch could be seen as a potentially empowering motif through it’s potential for disturbance. The glitch represents the mercurial and flawed nature of representation itself, and further subverts the very raison d’etre of technology. When technology is designed to harbour perfection and eliminate error, the glitch and its erratic spontaneity poses as disruption. In her E-Flux essay, ‘Asian Futurism and the Non-Other’, Xin Wang observes that technology can unveil ontological truth. Whilst Wang recognises the importance of histories of struggle and representation identity politics, she concludes that “[Asian Futurism] should instead propagate different avenues of inquiry that facilitate radical speculation forwards and backwards… it may very well engender new tools for political action but needs not serve any utilitarian end besides producing ‘strange, new wisdom’”. [8] Indeed, the glitch represents Wong’s awareness of our condition as ‘robots’, favouring instead the defiance of ‘cyborgs.’ Perhaps it is in these spectral anomalies of static that a contrapuntal and entirely new human experience awaits.

[1] Jordan Baker, “China debate raises spectre of White Australia Policy, says uni chief,” Sydney Morning Herald, August 23, 2019, https://www.smh.com.au/education/china-debate-raises-spectre-of-white-australia-policy-says-uni-chief-20190823-p52k67.html

[2] David S. Roh, Betsy Huang, Greta A. Niu, “An Introduction” in Technologizing Orientalism, ed. David S. Roh, Betsy Huang, Greta A. Niu (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2015), 2.

[3] Ibid., 10.

[4] Ibid., 15.

[5] Dawn Chan, “Asia-Futurism,” Artforum 54, no. 10 (Summer 2016): https://www.artforum.com/print/201606/asia-futurism-60088

[6]Donna Haraway, “The Cyborg Manifesto,” in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: the Reinvention of Nature, ed. Donna Haraway (New Jersey: Routledge, 1991), 163.

[7] Chela Sandoval, Methodology of the Oppressed (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

[8] Xin Wang, “Asian Futurism and the Non-Other” E-Flux 81 (April, 2017): https://www.e-flux.com/journal/81/126662/asian-futurism-and-the-non-other/

1 thought on “Zoe Wong’s Oriental Futures”