On March 18 this year I took part in a panel at Melbourne Town Hall organised by the Multicultural Centre for Women’s Health. The event brought together feminists from multicultural backgrounds to talk about the relevance of feminism in our lives: myself, a Shanghainese-Melburnian writer and media-maker; Durkhanai Ayubi, a freelance journalist, first generation Afghan-Australian and Senior Policy Analyst for the Federal Government, discussing feminism and Western imperialism; and Dr Odette Kelada, a lecturer in the University of Melbourne Indigenous Studies Department who spoke about feminism, race and whiteness. You can listen to an abridged podcast of our talks here thanks to Women on the Line, a program on 3cr Community Radio in Melbourne. The text of my talk is below.

I want to start by acknowledging again that we stand on Aboriginal land, on what is, always was and will forever be the country of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation, no matter how hard colonisation works through violence, lies and silence to make people forget it. I also want to acknowledge and honour the work that Aboriginal women like Jackie Huggins, Aileen Moreton-Robinson and Larissa Behrendt have done and continue to do in interrogating and critiquing the whiteness of Australian feminism, and developing understandings of gendered oppression that move beyond Anglocentric assumptions. I hope that our ideas and stories tonight can add to the discussions that these women have started around feminism, culture, liberation and intersectionality.

My family and I migrated to Melbourne from Shanghai when I was four years old, so I call myself a 1.5 generation migrant. I also call myself a person of colour, which is a political identity based around solidarity between people who are racialised as non-white in this society. Race might have been discredited scientifically but is still very much real as an axis of social oppression.

There are a lot of overlaps and differences between the experiences of migrants of all ethnicities, of people of colour whether Indigenous or from immigrant backgrounds, and of anyone whose culture is significantly different from Anglo-Australian culture, but because these things are all tangled up in my life I never know for sure which is the most pertinent in any given situation. My friend Uma Kali Shakti was once asked if she was speaking as a black woman, and she said “well I’ve tried speaking as a green pear and it didn’t work” so in that spirit, everything I say comes from my particular position and none other; I can’t decide whether I am speaking as a woman or a migrant or a person of colour because everything I say always comes from all of me.

The question we started with today is “Does feminism speak for all women?”, and I think I don’t want it to try. I don’t want to speak for Indigenous women, for transgender women, for women in other countries and situations, even women whose lives might, in a glance, look similar to mine. I don’t want feminism as a monolithic ideology, no matter how inclusive; I want all women to be able to speak for themselves, as feminists or just as people who know what they need, and for that to be heard.

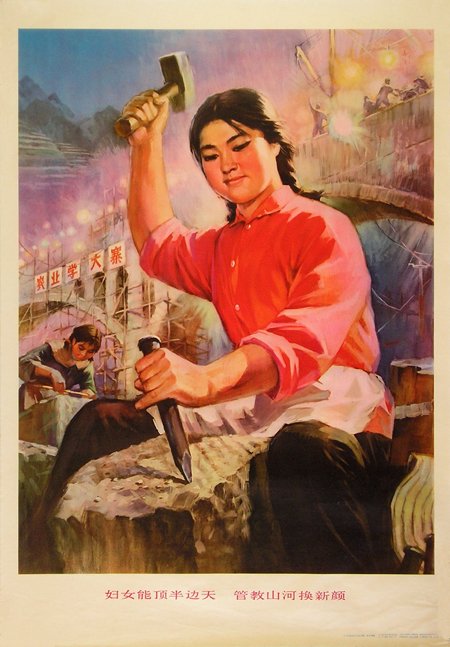

In talking about feminism and racial and cultural difference, often there is this expectation that women from “other” cultures are contending with these really backward values and that feminist liberation is going to look a lot like assimilation into Anglo-Australian culture. I hope we can all agree that’s not liberation, and see that cultural traditions and progressive values aren’t inherently in opposition. But even by the lens of urban middle-class white feminism, the lives of the women I come from don’t look like you might expect.

My grandmother is a feminist and turning 84 today. Well, she doesn’t know her actual birthdate because she had so many siblings they didn’t celebrate birthdays, plus she was born in the 1920s when China was in the middle of transitioning from the lunisolar Chinese calendar to the Gregorian calendar. So when she was asked for her date of birth she decided on March 18 because it was ten days after International Women’s Day. Her own mother, my great-grandmother, was illiterate and also a feminist, she saved and invested all her dowry money to send her daughters to school. Both my grandmothers were university-educated professional women who often earned more than their husbands. With my ah-bu an obstetrician and my nai-nai a botanist, and my own parents pushing me to study the “Asian five” in VCE (chemistry, physics, specialist maths, maths methods and compulsory English), it wasn’t until I was doing gender studies in my rebellious arts degree that I learned that Western culture associates “hard” sciences with masculinity.

Coming from the People’s Republic of China, the preoccupations of Western feminists in the 90s seemed a little disconnected from the lives of my mother, aunties and grandmothers. My first languages, Shanghainese and Mandarin, use gender-neutral pronouns in speech and for professions, titles and other descriptors. All the women I knew worked full-time, kept their names regardless of marriage as is Chinese tradition, and had free and legal access to contraception and abortion. I was born under the one-child policy, so it was easy for me to understand that reproductive rights for all women is not just about childcare, maternity leave and abortion but also the stigmatisation of women with large families in the majority world, of young mothers and single mothers; forced sterilisation of women with disabilities; custody rights for non-biological lesbian and transgender mothers; indefinite detention of refugee women and their children; and so many other issues. These are all feminist issues, and issues at the intersection of gender and poverty like Centrelink payments are no less feminist issues, and no more difficult and divisive than issues at the intersection of gender and wealth like representation in board rooms. Usually the phrase “intersectional feminism” is only used for minoritised women, as if women whose class and culture are privileged are not speaking from the intersection of those identities.

So what can feminists do to make feminism more relevant for all women? I think it’s important to work closely with other movements, such as movements for decarceration and refugee rights, because women’s lives don’t exist in a vacuum of gender. I’ve always called myself a feminist, but I don’t think it really matters whether someone calls themselves a feminist, womanist, for human rights or gender equality or women’s liberation, as long as we can agree on some basic values.

I want to bring up cultural sensitivity because I think feminism is often pitted against culture, multiculturalism and cultural subjectivism. I think it might be more useful to talk about a feminism that is politically sensitive and strategic rather than culturally appropriate. Feminism is strongest, sharpest and most successful in creating change when it comes from within a culture. When feminism responds to gendered oppression by pathologising a culture, that silences women and silences feminists. We need to recognise that women direct and define culture, that our cultures belong as much to us as the men in our communities. Women of all cultures work hard to prove that their feminism is their own and not a Western import. I think feminist solidarity needs to celebrate and support culturally specific feminisms more than trying to make one feminism speak to all situations or for all women.