I first watched Dr. Anita Ratnam perform when I was seven years old. Over the last two decades, I have followed her trajectory as an artist and went on to write a PhD about her work. Fifteen years ago, my mother commissioned a tour of Ratnam to the Middle East for a fundraiser.

In less than two weeks, she will be sharing her craft on Victorian shores in a tour steered by NIDA in partnership with Multicultural Arts Victoria, and supported by Arts Centre Melbourne, St. Martin’s Youth Arts Centre and Chunky Move. I, for one, am personally very excited for Melburnian audiences to experience Ratnam’s aesthetic, and in this essay I provide a birdseye view of the breadth of her repertoire. You can purchase tickets to her solo performance of Ma3Ka and artist talk on December 1st at Chunky Move here. Showing for one night only followed by a panel discussion with Dr Priya Srinivasan, Dr Will Peterson and the author.

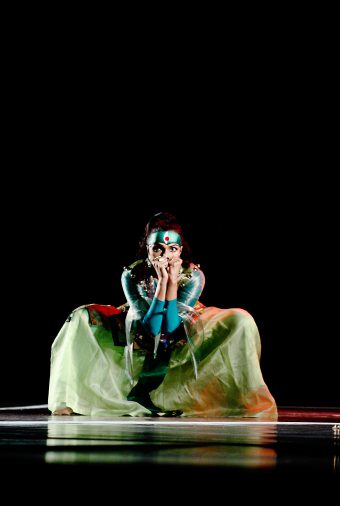

Dr. Anita Ratnam is a dancer, choreographer, artist, scholar, author, cultural activist, curator, collaborator, educationist, diarist and fashionista. While she dons these many hats with relative ease, her multiple steps have worked in unison to mirror and distort notions of idealised Indian womanhood on and off stage.

Holding a PhD in Women’s Studies, the intersections of dance, gender, sexuality and culture are subjects of interest in her body of work. Being intensively trained in the Indian classical dance forms of Bharatanatyam, Mohiniattam and Kathakali, she draws extensively on the vocabulary, semantics and grammar of these dance forms in her performance works, in addition to the martial arts traditions of Kalaripayattu and Tai Chi and the meditative traditions of Yoga and Qi Gong. The result is an aesthetic marked by minimalism and the power of suggestion. The spoken word is also of utmost importance in her performance works and she regularly uses conventions of traditional theatre in her performance-making processes and outcomes.

Considerable criticism was directed at her work when she started performing in the 1990s, and there still exists a deep sense of discomfort amongst traditionalists who do not understand how to situate her practice. Her response to such criticism has resulted in the hybrid form of individualised performance that she labelled ‘Neo Bharatam’ in the 1990s. In a candid conversation, she once told me that she had decided to call the form ‘Neo Bharatam’ after she’d seen the Hollywood blockbuster The Matrix, and Keanu Reaves’s character was called Neo. Ratnam defines Neo Bharatam as an individualised response to her art and life.

As a result of evolving a mode of praxis that is in continuous conversation with Ratnam’s own life experiences, Neo Bharatam remains open to the limitless possibilities produced by one’s muscle memories. It is important to acknowledge that Neo Bharatam is not a fusion form, for it is not the piecing together of multiple movement vocabularies for the sole purpose of aesthetic appeal or generation of fresh movement material. Rather, it is a reflexive performance praxis that serves a tripartite function:

- To stage the lived reality of Ratnam and her art in the here and now, through a performance tapestry that weaves together the dual strands of the particular sacred and the global secular. Her work is largely devised, choreographed and scripted in collaboration, and performed individually and is usually framed as a process of exploration.

- To critique the modes of representation of the Nayika—or heroine—in Bharatanatyam, by producing performance texts that reclaim power, desire and agency for the Indian woman on the theatre stage. Women form the central motifs of all of Ratnam’s works and are analysed through the prism of performance and mythology. Autobiographical strands inform Ratnam’s interpretation of these mythologies, and she does not shy away from the ‘feminist’ label. The personal and political concerns that she grapples with reverberate across her repertoire.

- To evolve a mode of contemporary performance that is rooted in Indian and pan-Asian performance traditions, thereby helping shape South Asian dance discourses without an adoption of the techniques and terminology used in Western dance discourses. Not one for imitation of the West, she does away with what she believes “white bodies can do better”. Her intent to work with Indian mythology and rework its reception and interpretation further complicates her position as a contemporary dancer and performance-maker working from Chennai, the home of neo-classical Bharatanatyam

In many ways, these functions feed off and into each other, and are hence not as separate as they may appear at first glance. Thus, Ratnam’s body in performance becomes the site for negotiations of gender and genre that are constantly in a state of flux. The strength of the patriarchy is continuously challenged in her work and she attempts to radically revolutionise the concept of the idealised Indian woman, carefully constructed as part of the larger nationalist movement in India in the country’s struggle for freedom from the British Empire. Dance Scholar Judith Lynne Hannah distils Mrinalini Sarabhai’s writings on the Nayika:

The plight of the male-defined ideal woman is depicted as longing, hesitation, sorrow, loneliness, anxiety, fear, parting, yearning, pleading, forgiveness, faithfulness, despondency, envy, self-disparagement, depression, derangement, madness, shame, grief and being rebuked, insulted and mocked by one’s family and deceived by one’s lover.

Further, the foremother of Indian contemporary dance, Chandralekha, questioned “the appropriateness of as basic a convention as the yearning of a female dancer for her male lover, her master, her God”. Ratnam denies this type of identity and representation of the feminine in her work, and develops the idea of what she terms the “female transcendental”. She asserts, “Dance is my attempt to populate the world with interesting women. Some of them are those we recognize as goddesses. They have mischief, rage, anger. They can kill, protect, laugh, they have sensual power. They are, I hope, enigmatic, complete, intelligent, passionate”.

Additionally, her aesthetic adopts breath, silence, stillness and energies as choreographic devices to critique the modes of representations afforded to the female dancer, as will be witnessed in her upcoming solo performance of Ma3Ka.

Now in her sixties, Ratnam speaks of a sort of Alzheimer’s of the body. She is interested in exploring a return to Bharatanatyam as she feels her body is forgetting other movement vocabularies, but her muscle memory vividly remembers the Bharatanatyam body as it returns to its powers of recall. The sweet sound of decolonisation, perhaps?